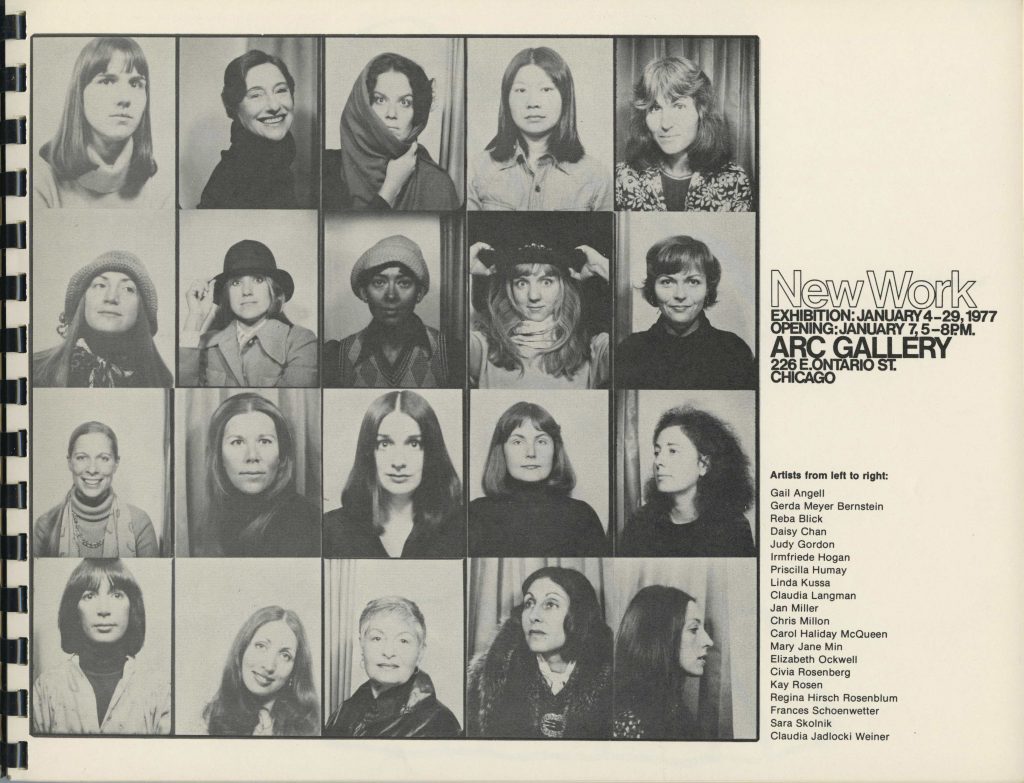

In 1973, fifteen women artists joined together to form ARC (Artists, Residents, Chicago), one of the longest-operating women’s cooperative galleries in the country to date. Frustrated with the lack of professional support available to female artists and the disproportionate amount of representation men had in commercial galleries at the time, ARC’s founders set out to create their own space for exhibition and continued education. The gallery’s first location, in a building across the street from the then relatively new Museum of Contemporary Art, situated it near the center of Chicago’s growing art scene. In the decades that followed, ARC would go on to launch the careers of many women artists working outside of traditional mediums and themes. Gardner-Huggett 2017, 201, 38

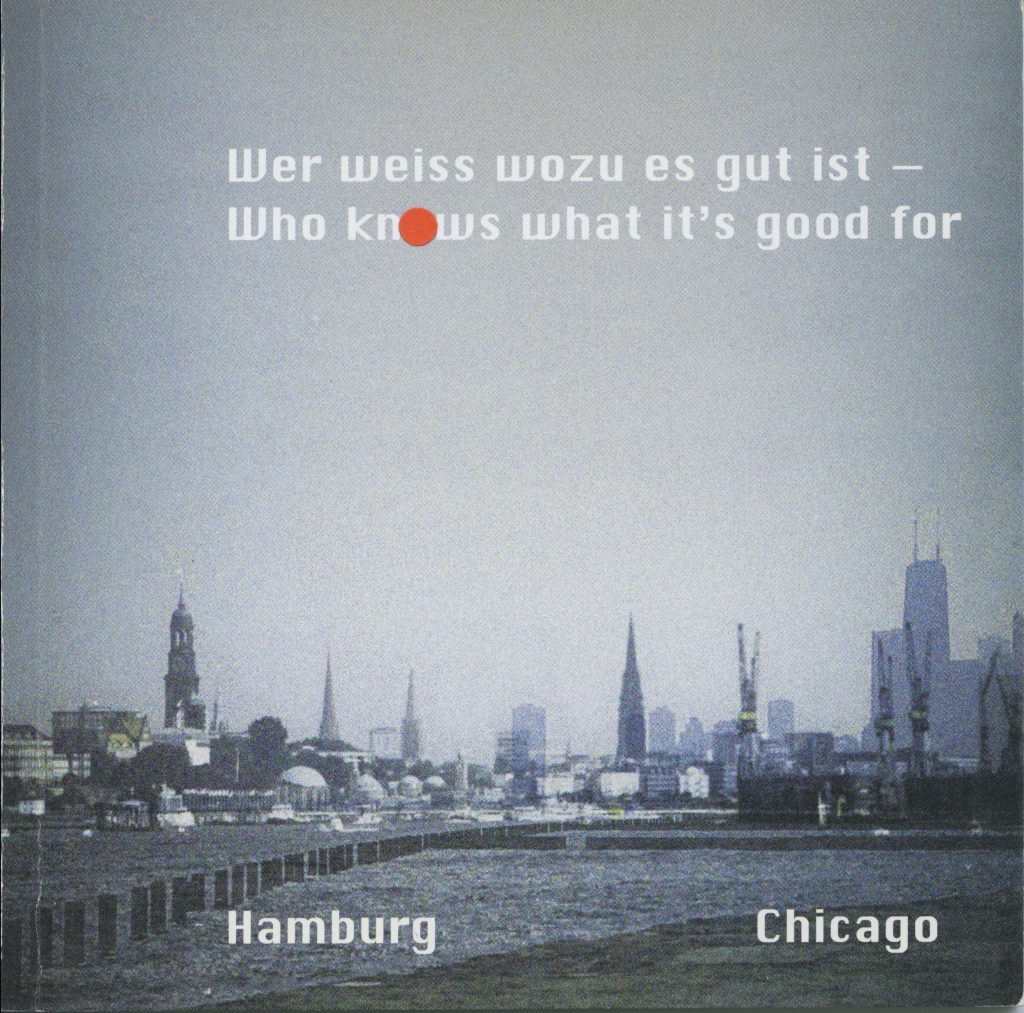

In 1979, ARC opened Raw Space, a bare-bones basement gallery dedicated exclusively to the exhibition of installation art. As one of the few alternative spaces that offered honorariums to participating installation artists, Raw Space attracted artists from across the country. Gardner-Huggett 2017, 47 Thus, what had begun as a hyper-local community, composed predominantly of students and alumni of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, quickly grew to include artists from different regions, backgrounds, and practices. This expansion—along with ARC’s diverse programming that included visiting artist lectures, international art exchanges, and educational workshops—provided women artists with new opportunities for dialogue and exposure, distinguishing it as a model for alternative gallery operations and community-building. ARC Gallery Records

In exchange for the opportunity to exhibit their work, members of ARC were expected to pay monthly dues, participate in democratic decision-making, and dedicate a regular number of hours to the gallery’s upkeep. Unlike the commercial galleries that took a significant cut from their artists’ sales, ARC members kept 100% of their proceeds. In the absence of the profit-driven eye of a commercial gallery director—who likely would have shied away from overtly political, personal, or off-trend work—ARC artists had the freedom to create and exhibit experimental work that spoke directly to their experiences as women.

In many ways, ARC’s membership model opened doors to women who might have otherwise been excluded from the art world. But it also imposed a financial threshold. Membership demanded time and money, of which many women artists, who were often also wives and mothers, were in short supply. Those who had trouble fulfilling their membership duties and expenses sometimes faced expulsion, a difficult decision for the women in leadership positions who valued inclusion yet had to ensure the gallery’s rent got paid.

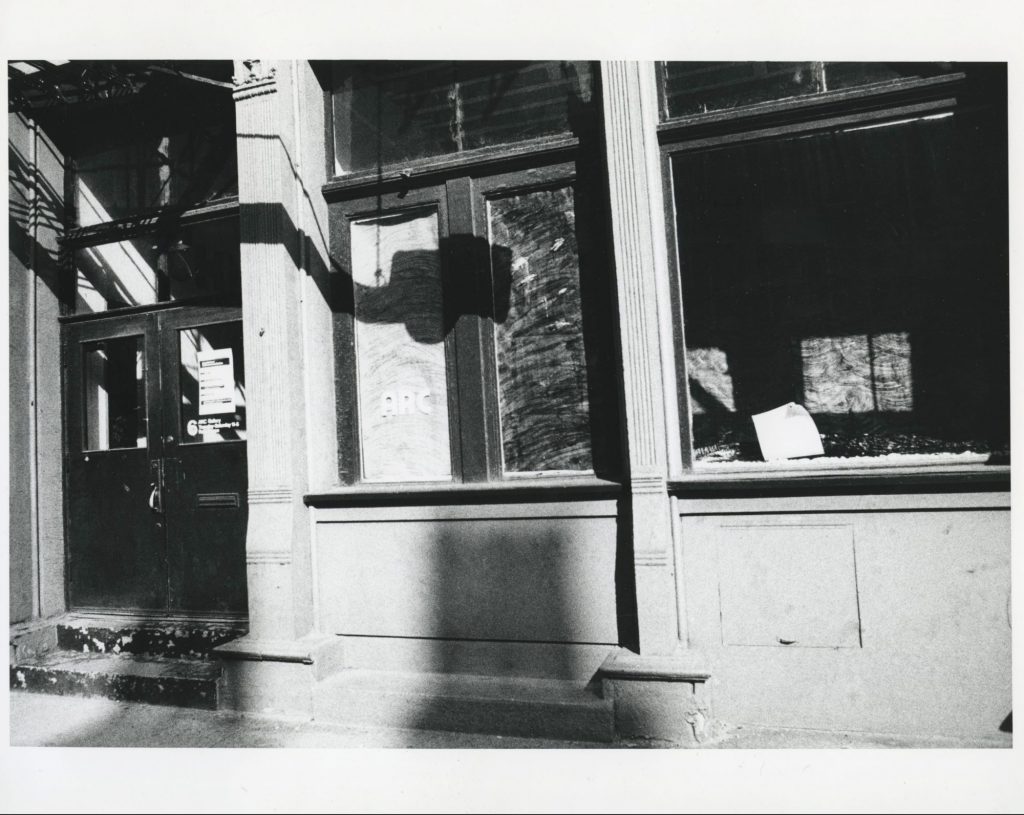

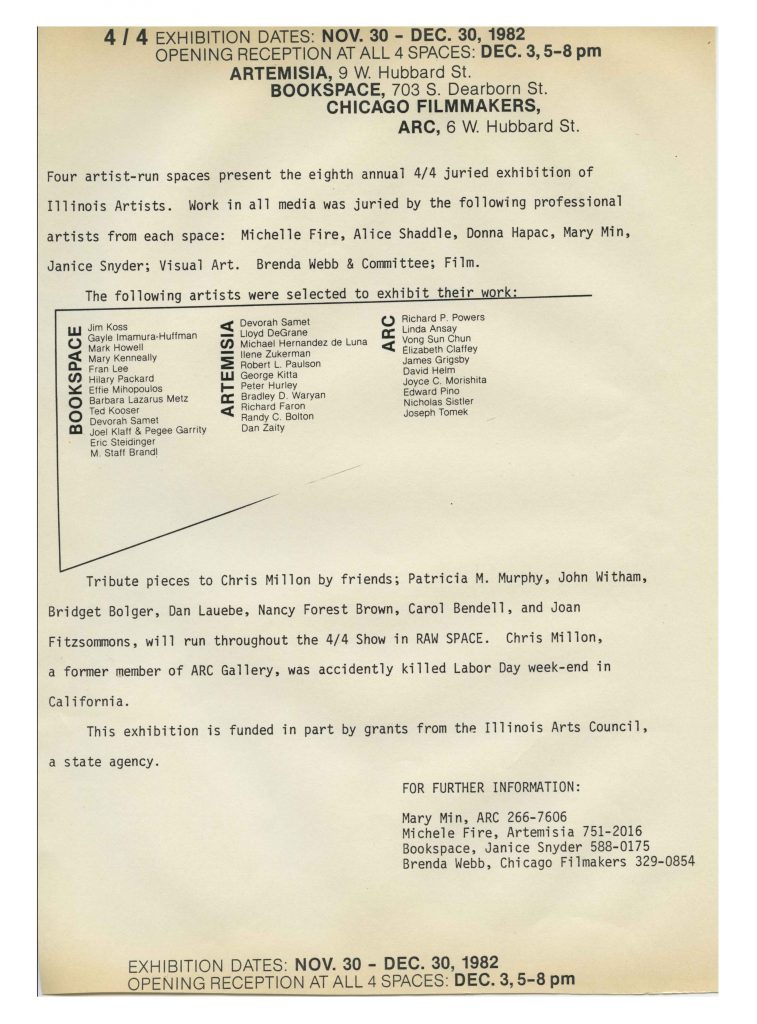

But ARC’s financial sustainability depended on more than just its members’ contributions. A large portion of ARC’s funding came from government grants and philanthropic sources, including the Illinois Arts Council, the Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the John D and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Midcon Corp., Sara Lee Foundation and the Polk Brothers Foundation. ARC Gallery Records However resourceful, these sources were hardly reliable, as their budgets ebbed and flowed with the politics and economy of the day. When the Reagan administration came to power in 1981, the National Endowment for the Arts budget shrunk by 12%. Knight 2011 Without this extra aid, ARC could no longer afford its then-home on Hubbard Street, where it had thrived for five years alongside fellow artist-run spaces Artemisia, N.A.M.E., Chicago Filmmakers, the Chicago Editing Center, and East Hubbard Gallery. ARC’s subsequent move to 356 W. Huron would be just one of many relocations, as rising rents continued to hound the gallery from one neighborhood to the next.

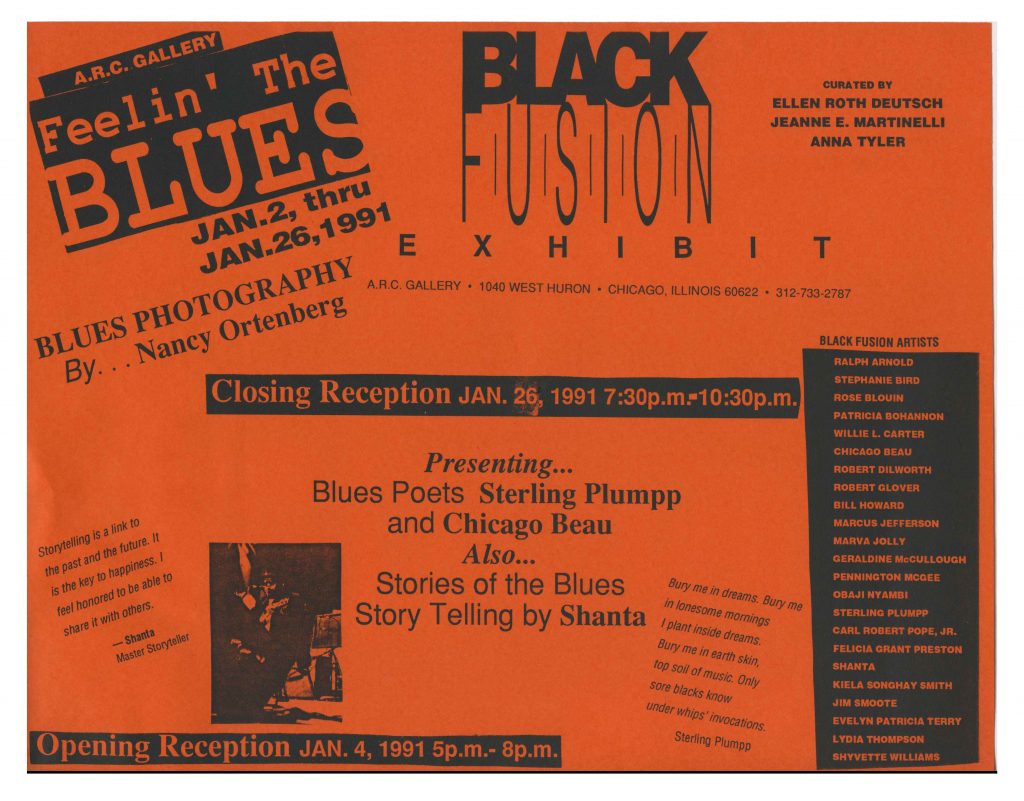

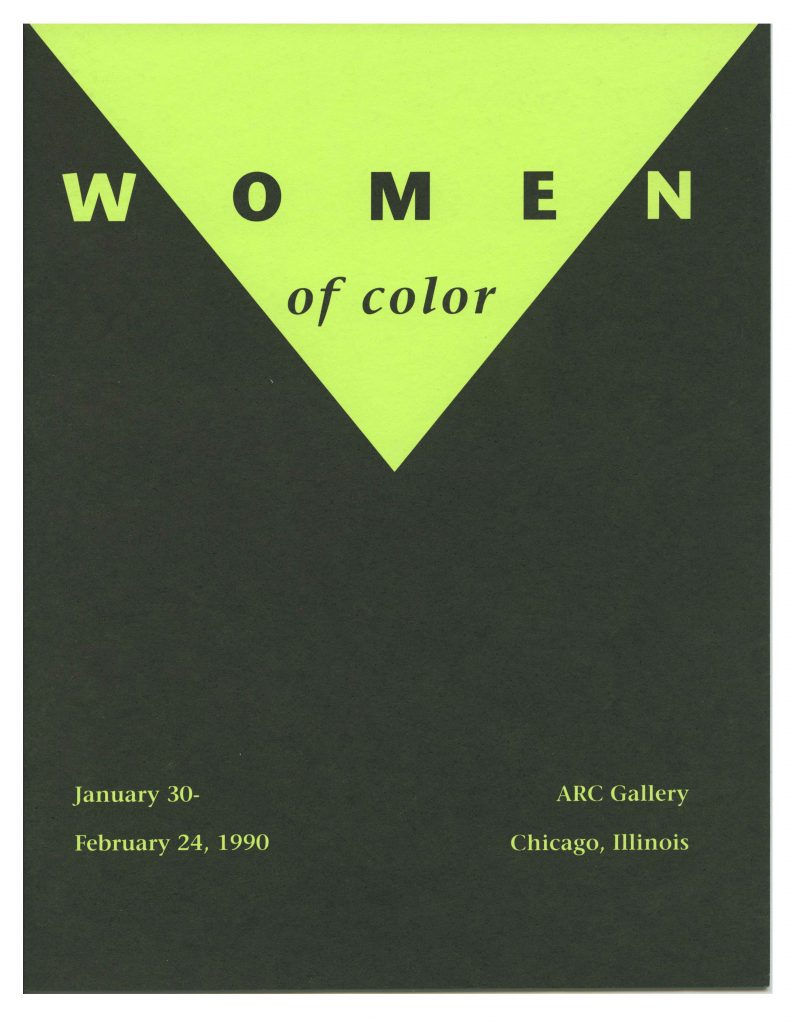

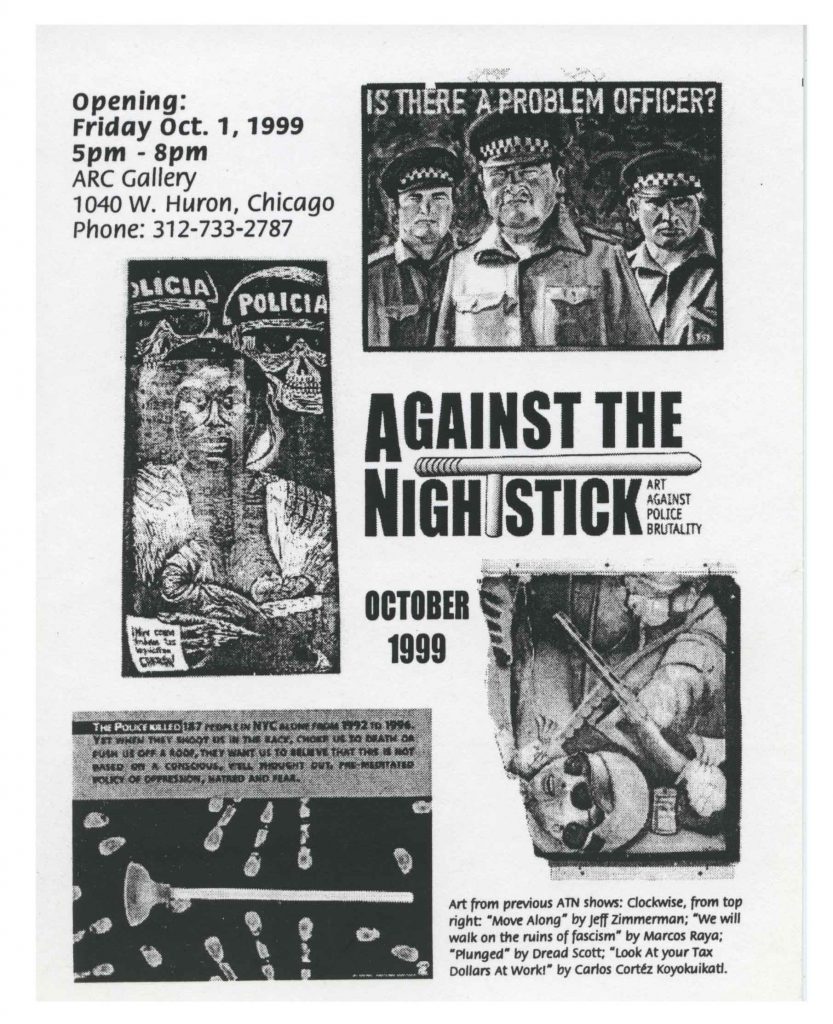

Despite its transience, ARC has managed to sustain a steady schedule of innovative exhibitions and events since its founding. Touchy Subjects, an exhibition mounted in 1990, featured art for and by people who were visually impaired. Visitors were invited to feel and interact with the sculptures, constructions, and wall pieces throughout the room. That same year, ARC opened Women of Color, an exhibition of artwork by Black and Hispanic women artists curated by Ramon Price, then the Director of the Curatorial Department of the DuSable Museum of African-American History, and Deanna Bertoncini of the Latino Arts Gallery. An accompanying panel discussion “revealed the mixed emotions felt by the artists about the contradictions between encouraging exhibition opportunities for minority artists and the fear of ‘ghettoization’ that occurs when such ‘theme’ exhibitions are held,” writes Ellen Roth Deutsch in the ARC 20th Anniversary Catalog. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, ARC continued to use its exhibitions to explore pressing, sometimes contentious topics, such as abortion, AIDS, police brutality, and domestic violence. The gallery also worked to engage artists from beyond the local scene; in 1993, National Exposure opened, the first in a series of annual exhibitions featuring the work of photographers from across the country. ARC Gallery Records

Since its opening, ARC has belonged to a larger network of alternative galleries in Chicago, including N.A.M.E. Gallery, Randolph Street Gallery, and Artemisia Gallery, with whom ARC shared more than just a wall in its early years. Like ARC, Artemisia modeled its operations after A.I.R. in New York, whose democratic and separatist ideology informed both galleries’ women-only membership structures. As two of the only art spaces in the city created specifically by and for women, ARC and Artemisia naturally supported one another, often collaborating on programming, such as 4/4, an annual exhibition of Illinois artists juried by four artist-run spaces in Chicago. However, though the two galleries aligned in many ways, they also had distinctive identities and influences. While Artemisia’s members subscribed to a more ideological feminism, ARC was more practical in its approach to supporting women, and focused its educational efforts on professional development and networking opportunities rather than feminist theory. It is possible that this practical approach may in part have contributed to ARC’s longevity, while Artemisia’s feminist reputation may have alienated potential affiliates and donors.