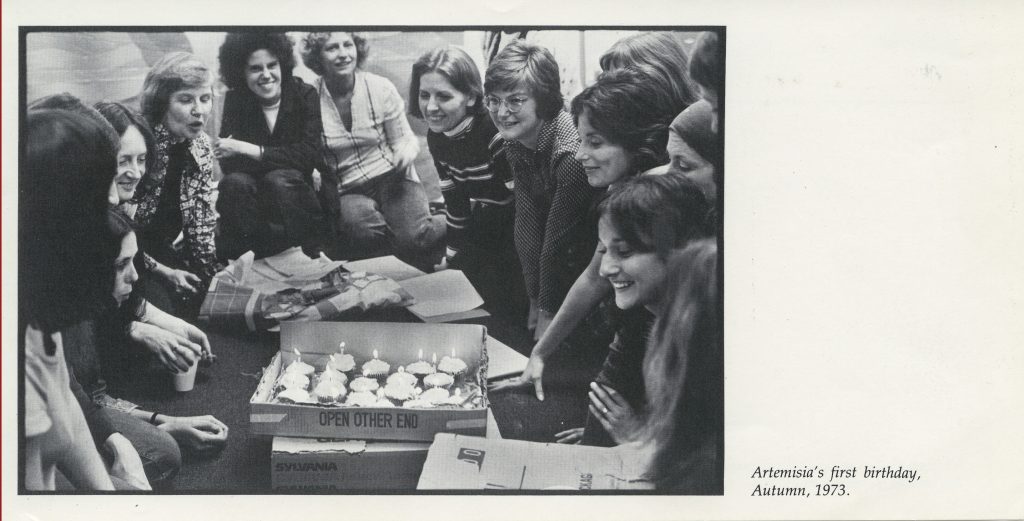

In the autumn of 1973, Artemisia opened down the hall from ARC at 226 East Ontario.

Artemisia’s cooperative model, much like ARC’s, was inspired by A.I.R. Gallery in New York. In the spring of 1973, a School of the Art Institute of Chicago graduate student named Joy Poe attended the First Annual Midwest Conference of Women Artists, organized by the Chicago branch of West-East Bag, a national women’s artists network. At the conference, the artist Harmony Hammond presented a video about A.I.R. Gallery, a women’s cooperative gallery in New York City that had formed the year prior.1 Inspired, Poe decided to visit A.I.R. that May. Upon returning to Chicago, Poe began hosting meetings with fellow women artists to discuss the possibility of forming a cooperative gallery of their own. Interest in the idea grew rapidly, and within a few meetings, Artemisia’s initial five members were chosen: Barbara Grad, Margaret Harper Wharton, Emily Pinkowski, Phyllis MacDonald, and Joy Poe. These five then selected an additional fifteen members: Phyllis Bramson, Shirley Federow, Sandra Gierke, Carol Harmel, Vera Klement, Linda Kramer, Susan Michod, Sandra Perlow, Claire Prussian, Nancy Redmond, Christine Rojek, Heidi Seidelhuber, Alice Shaddle, Mary Stoppert, and Carol Turchan—many of whom were also current or former graduate students at SAIC. Gardner-Huggett 2017, 2-1, 37-65

Naming themselves after the seventeenth century Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1597-c.1651), “whose best work had been credited to her father,” the gallery’s founding members sought to create a space in which women artists could achieve visibility and participate in meaningful artistic community. Though it possessed feminist undertones, the choice of the name Artemisia was also a way out of using a name with the word “woman” in it, which could have limited the gallery’s reach and future appeal. Nevertheless, Artemisia quickly gained a reputation for promoting feminist ideas through topical exhibitions and educational events. Gardner-Huggett 2012, 55-56

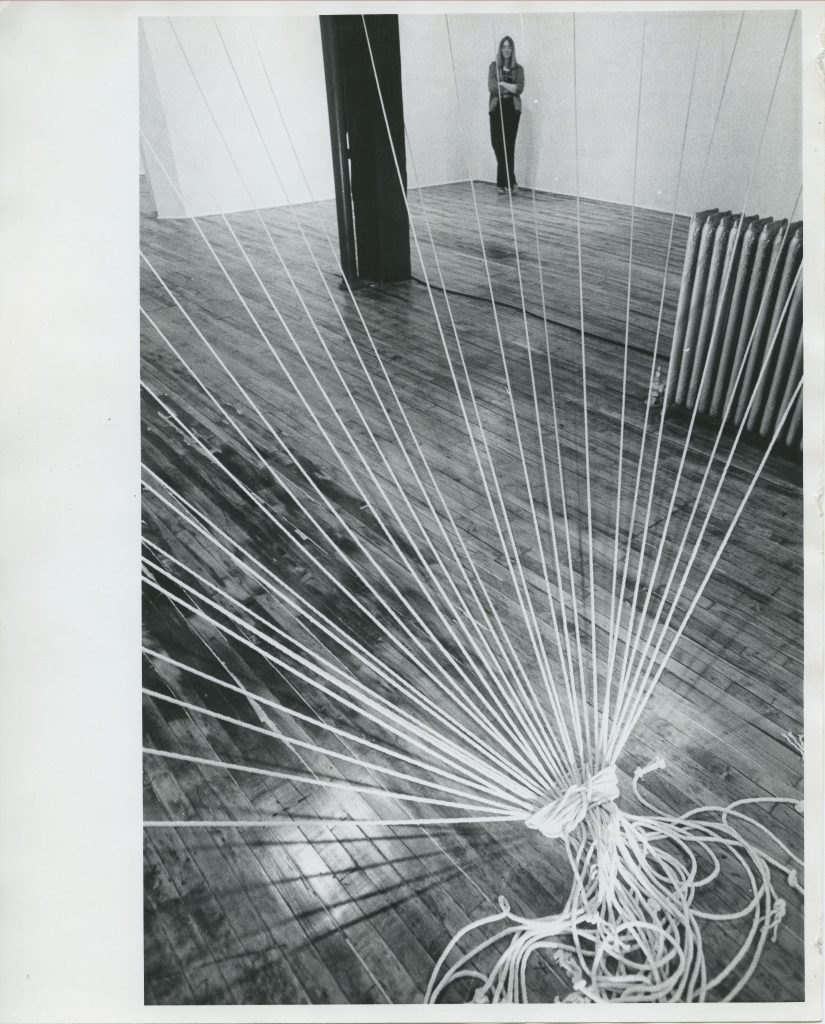

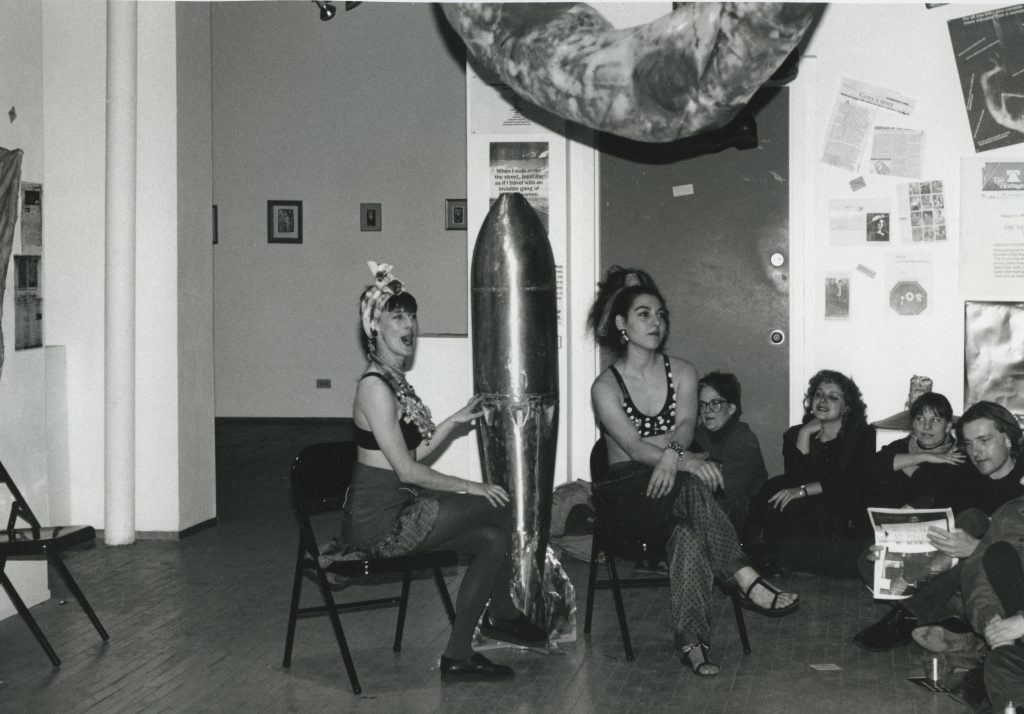

In its first few years alone, the gallery brought in a diverse array of female guest speakers. Working artists, professors, and curators—including but not limited to faculty at the Art Institute of Chicago and The Whitney—came to Artemisia to facilitate lectures and workshops on the topic of women in the arts. From the systemic erasure of women in the study of art history to the challenges of being a woman in the male-dominated field of architecture, Artemisia’s relevant programming offered members the opportunity to reflect on–and tactfully navigate–their identities as women artists. While not all such programming was overtly political, some was. In 1979, Artemisia hosted a seminal group show entitled Both Sides Now: An International Exhibition Integrating Feminism and Leftist Politics. Guest-curated by feminist critic/art historian Lucy Lippard, the exhibition featured the work of contemporary women artists from across the world, including Martha Rosler, Donna Henes, Betsy Damon, Leslie Labowitz, Susanne Lacy, Alexis Hunter, Mary Kelly, Margaret Harrison, Marie Yates, and Adrian Piper.

That same year, the gallery became the subject of nationwide controversy when Joy Poe staged an exhibition entitled Ring True Taboo. Though she intended to make a commentary about societal complicity in sexual assault against women, her means of doing so—by enlisting a male actor to publicly “rape” her in the middle of opening night—outraged and disturbed her audience members. Ring True Taboo received national media attention, splitting followers of the feminist movement into two camps: those who believed Poe’s performance was a necessary provocation, and those who believed it was a needless and harmful violation of the social code. Poe’s performance raised the question of consent and censorship in the public consumption of art: by entering a gallery space, were you consenting to anything the artist might subject you to? Where was the line between intentional subversion and abuse of power? Many of the Artemisia members to whom the rape performance was a surprise believed an irredeemable transgression had occurred, and called for Poe’s resignation. When they ultimately put it to a vote, the members elected to have Poe stay, but a month or so later, she resigned of her own accord. Joy Poe’s personal archive accounts for a significant portion of the Artemisia records housed at the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago. Including candid journal entries from the period as well as scrupulous accounts of the gallery’s programming, Poe’s archive testifies to the extent of her dedication to Artemisia and her life as an artist.

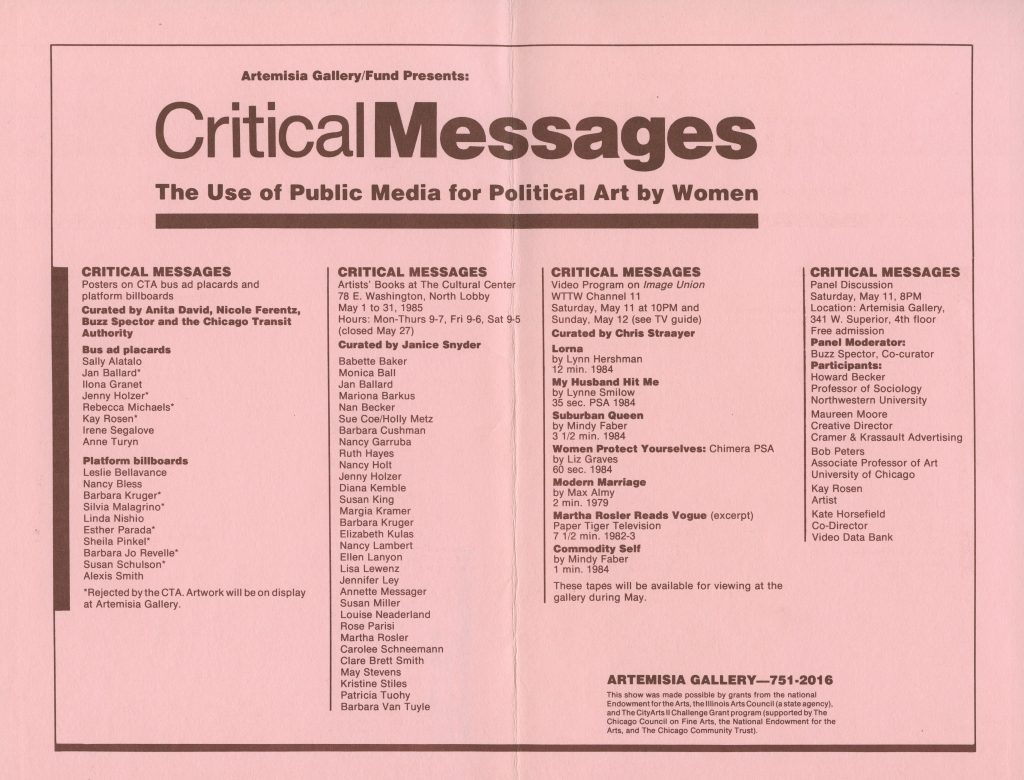

In 1985, Artemisia made another splash with the exhibition Critical Messages—Public Media for Political Art. The original plan for the exhibition was to enlist 18 artists from across the country, including Jenny Holzer, Kay Rosen and Barbara Kruger, to create reproducible images that could fill 500 ad spaces on Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) buses, subway stations, and train platforms. However, shortly before the show was supposed to mount, the CTA rejected 10 of the 18 pieces that addressed or critiqued issues of misogyny, race, war, the military industrial complex, nuclear proliferation, and President Ronald Reagan. Though the CTA’s censorship prohibited more than half of the artworks from appearing on public transit, the rejected pieces did make it to the walls of Artemisia’s gallery space, and many were reprinted in local newspapers covering the controversy.

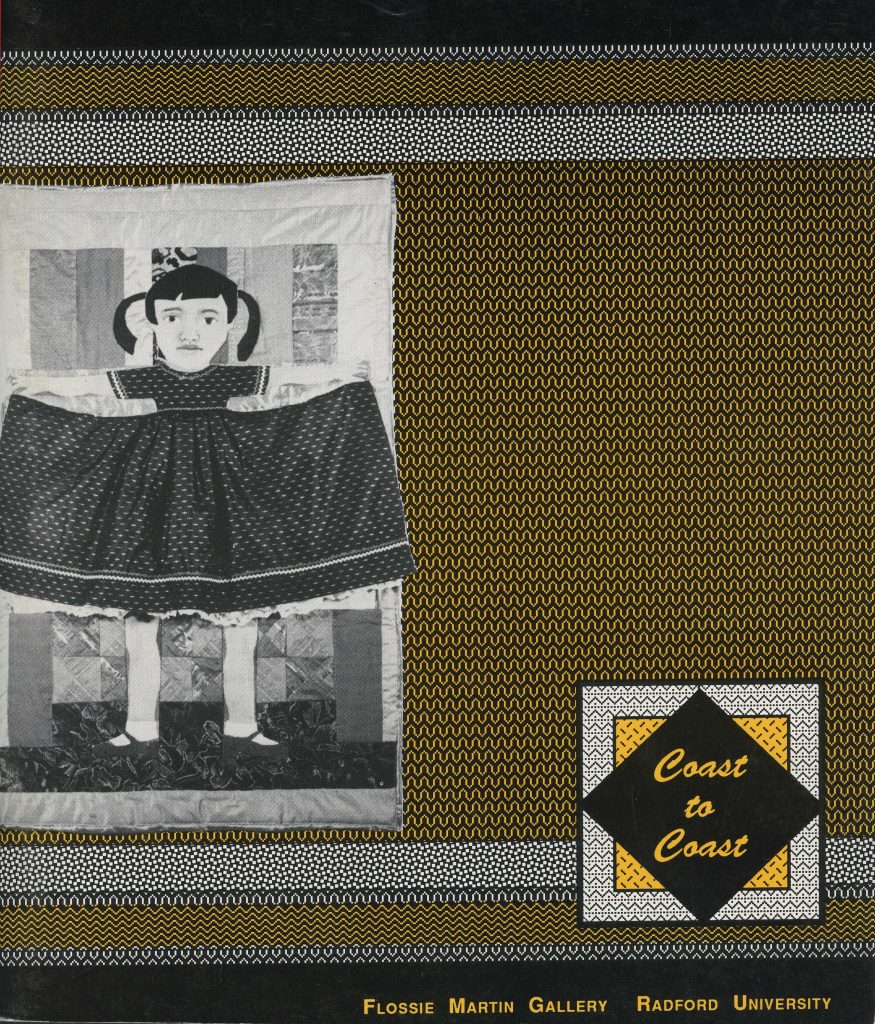

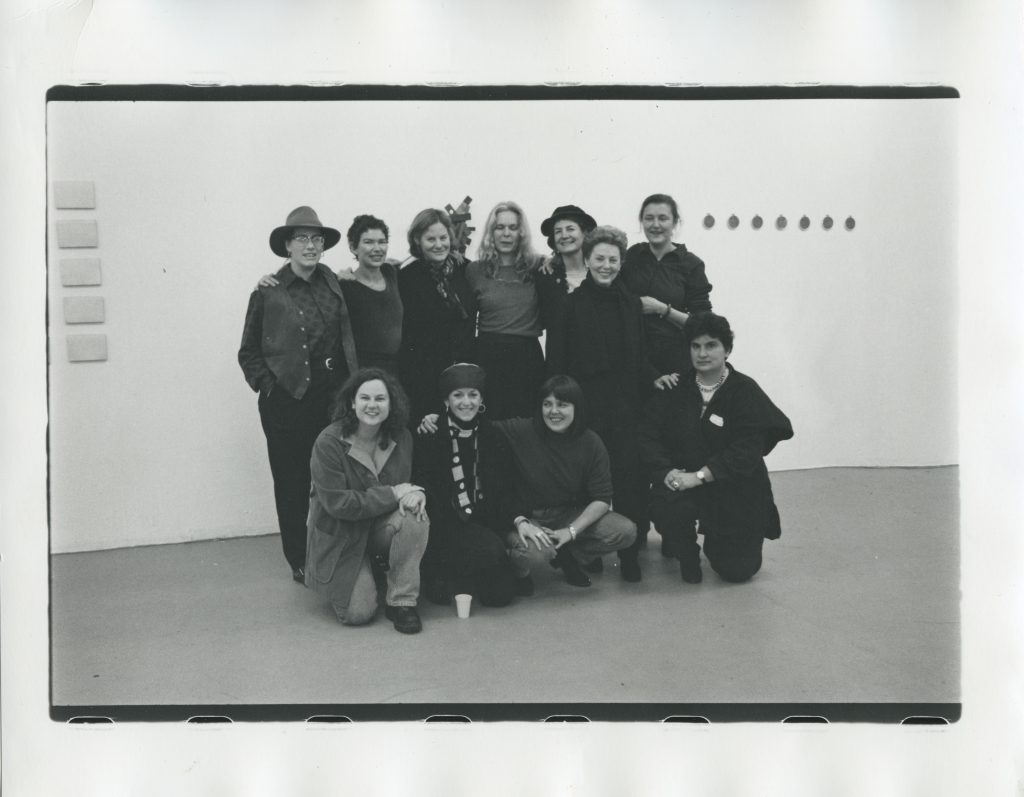

By the late 1980s/early 1990s, Artemisia’s separatist feminist ideology had proven to be effective in creating community and access for a particular demographic of women—mainly, middle class white women. In an attempt to reach more women of color, in 1990 Artemisia hosted Coast to Coast, a traveling exhibition featuring books made by over 130 women artists of color. In 1994, Artemisia expanded its diversity and inclusion efforts by creating an annual mentorship program that aimed to recruit new art school graduates and women who had been working on their own but had not yet made the leap into the professional arena. Consisting of lectures, practical workshops, individual meetings, and exhibition opportunities, the program succeeded in bringing a wider range of women artists into Artemisia’s circle.

In addition to its regional and national programming, Artemisia participated in a number of international art exchanges aimed at fostering cross-cultural dialogue and exposure. In August 1997, the exhibition Between Ego and Society: Exhibition of Contemporary Women Artists of China featured emerging women artists such as Yin Xiuzhen, who has since achieved international status and was included in the Brooklyn Museum’s 2007 exhibition Global Feminisms, the first international exhibition dedicated exclusively to feminist art from 1990 to the present.

Artemisia maintained a steady roster of exhibitions and programming until 2003, when a suspension of a major grant from the Jahn Foundation led to the gallery’s permanent closure. Gardner-Huggett 2012, 69