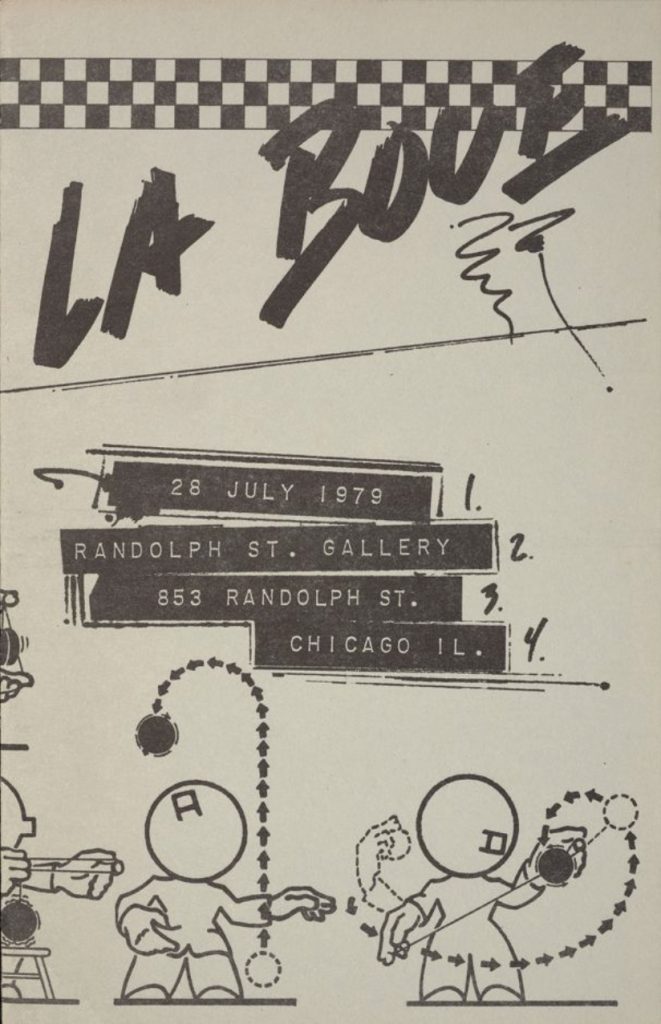

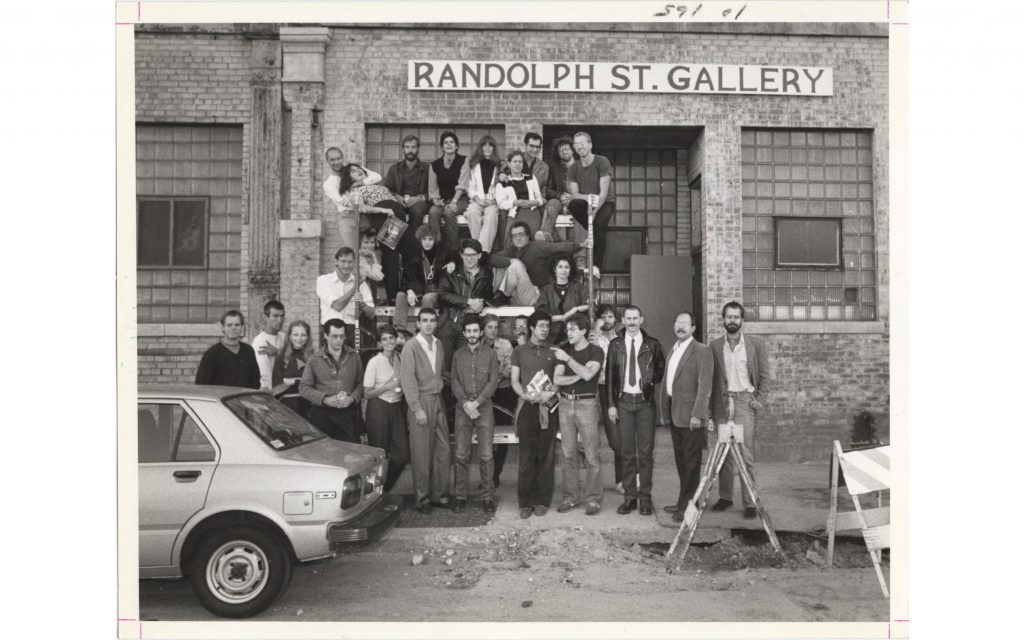

Randolph Street Gallery (RSG) was founded in 1979 by friends Sarah Schwartz, a sculptor with a degree from the School of the Art Institute (SAIC), and Patricia Miller, a trained art therapist. Blackstone 2023, 17 Having observed the limitations of the cooperative model in spaces like A.R.C., Artemisia, and N.A.M.E. Gallery, the women strove to create an artist-run space that was “an alternative to the alternatives.” Blackstone 2023, 35 Over the course of its first three years, RSG exhibited around three hundred local artists in and around Schwartz’s industrial warehouse apartment on West Randolph Street, which doubled as the gallery space. Photographs from this period document a series of outdoor installations staged in alleys, gangways, and vacant lots near Schwartz’ apartment, reflecting the founders’ initial intent to exhibit “noncommercial, large-scale” artworks. In 1981, the gallery moved down the block to 835 W. Randolph Street. By this point, Schwartz and Miller were both on their way out, and a new flock of leaders had begun to revamp RSG’s programming with thematic group shows and performance art. Sorkin 2018, 268

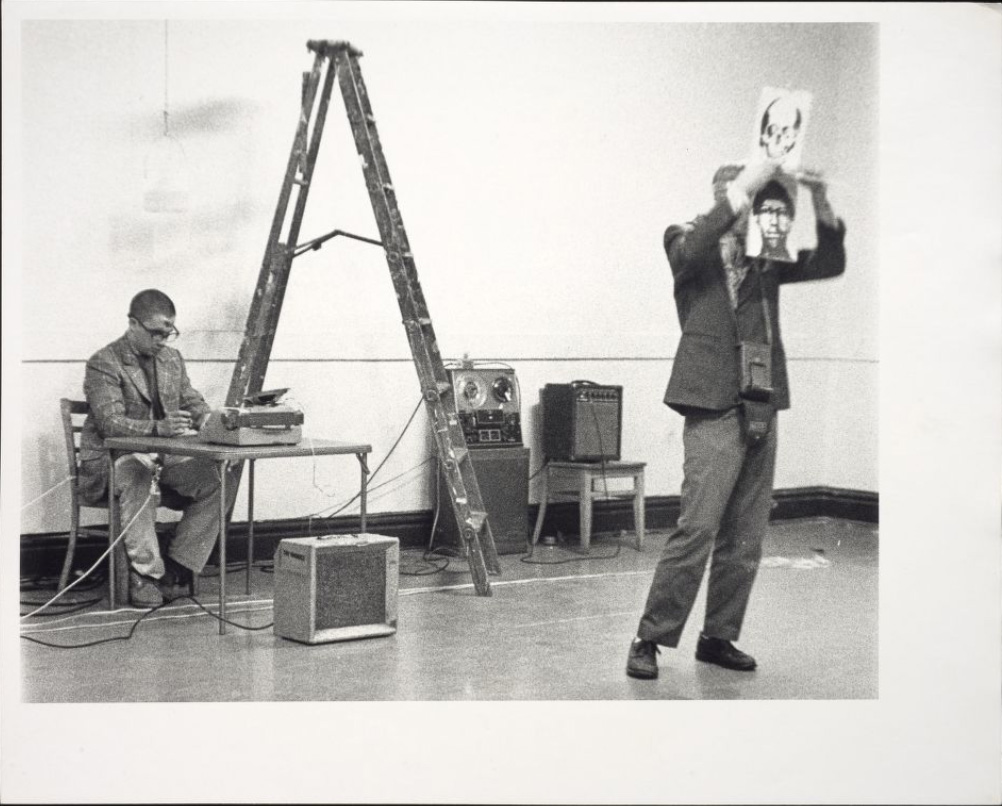

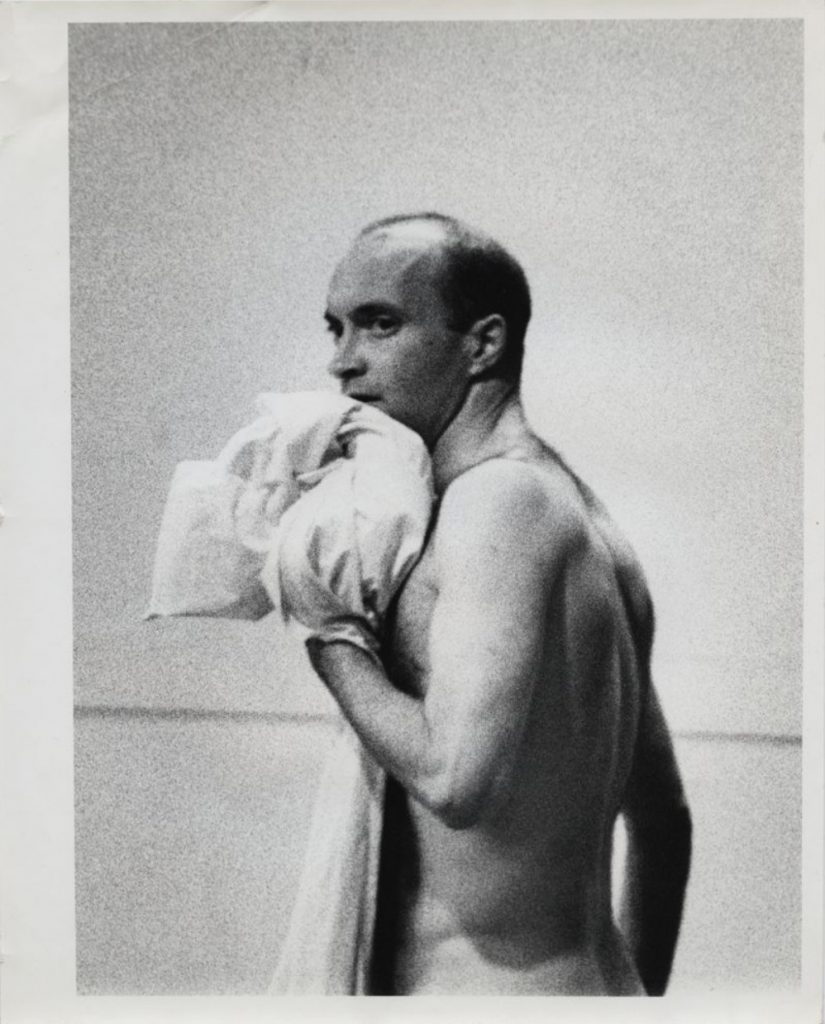

In 1982, RSG moved again to the space that would become its long term home: 756 North Milwaukee Avenue. (As of 2023, the address is now home to yet another iconic Chicago gallery, Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.) The new space was significantly larger in order to accommodate RSG’s rapid growth. By this time, the gallery had attracted the support of notable local art dealers and professionals, including Rhona Hoffman, Donald Young, and Lewis Manilow, all of whom served on RSG’s advisory board. Mary Min, a founding member of ARC Gallery, was hired as the executive director. Sorkin 2018, 260 Meanwhile, the multidisciplinary artist and dancer known as Hudson became the gallery’s first curator of “Time Arts,” a designation that encompassed experimental performances, video art, staged productions, poetry readings, and more. Blackstone 2023, 27 Like many of the artists and curators who passed through RSG, Hudson would go on to develop an illustrious career of his own, most notably as the esoteric, trend-averse director of Feature Gallery. Smith 2014 In 1986, Director Mary Min was succeeded by Peter Taub, Blackstone 2023, 50 who ran the gallery for a decade before becoming Director of Performance Arts at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Chicago Dancemakers Forum 2023

Throughout the 1980s and into the ‘90s, RSG shaped the creative and professional approaches of many seminal artists and curators. The gallery’s anti-establishment ethos created a space in which the ultimate goal of the artist was not to promote and sell their work, but to partake in a collective effort to advocate for the exhibition of new and experimental art. As a result, artists took on more responsibilities within RSG’s governance, blurring the line between artist and administrator. Taub and Hixson 2018, 369

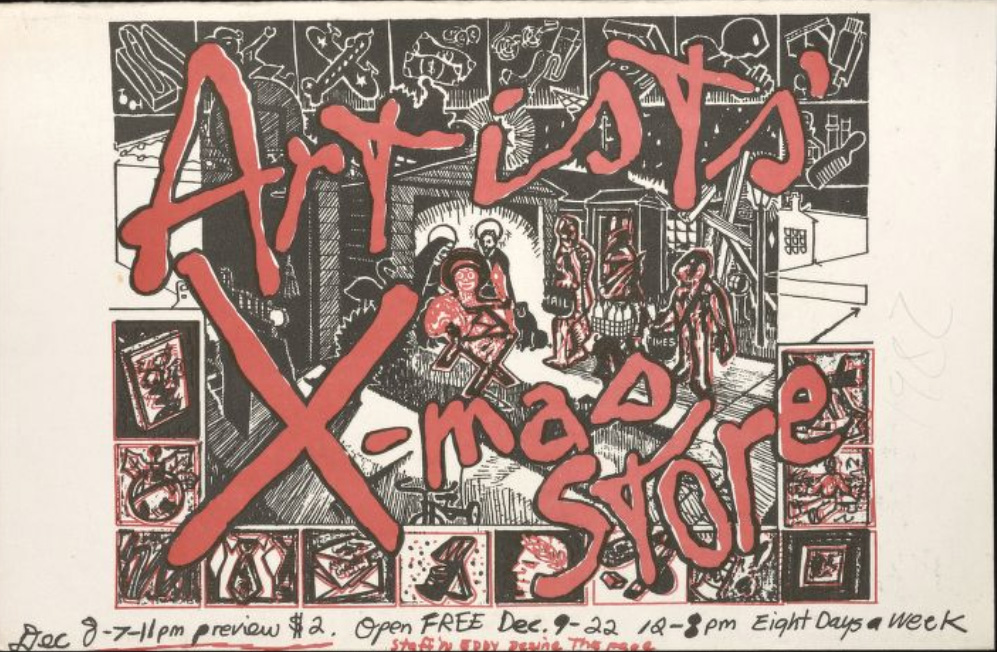

RSG’s provisional structure and inventive programming attracted artists whose work was, by nature, multidisciplinary, shapeshifting, and transitory. In 1986, Peter Taub and performance artist Brendan de Vallance launched P-Form magazine, which provided vital documentation of the performance art happening at RSG and other venues across the city. In the pages of P-form, one-time performances that would have otherwise been overlooked by anyone other than the original audience could be preserved through photographs, interviews, and commentary. This, along with RSG’s growing practice of taping performances, established performance art as a medium worthy of Chicago’s attention and patronage.

Throughout its existence, RSG was careful not to align itself with any one style or ideology. Instead, it opened its walls (and floors) up to a large range of artists and cultural figures. An annual performance and event series called In Through the Out Door brough in international LGBTQ figures such as the lesbian poet Eileen Myles, queer theorist Lauren Berlant, and zine artists G.B. Jones and Jena Von Brucker. RSG further extended its reach by collaborating with local and national organizations, such as the Cultural Center and the National Afro-American Museum, with whom RSG developed the Regional Artists’ Project (RAP), a grant program for individual artists and small collective groups whose projects challenged or extended cultural traditions or artistic expressions.

As RSG’s reputation grew, so did the pressure to secure funding in the form of government grants. From its inception, the majority of RSG’s operating budget was funded by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), which freed the gallery from seeking revenue through the sale of artwork or membership fees. In 1990, RSG was awarded $72,000 in the form of an NEA Advancement Grant, a sum it was expected to match by the following year. While the grant money bolstered RSG’s ability to hire staff and expand its programming, it also forced the gallery to think more like a commercial institution—toward sustainability and public appeal. In the following years, the gallery struggled to maintain its original ethos while conforming to the NEA’s evolving agenda. Blackstone 2023, 66-68

By the late 1990s, the NEA had undergone a significant budget cut, impairing its ability to fund RSG. Meanwhile, the nonprofit sector was professionalizing. RSG employees who were previously fueled by passion now sought proper compensation, while the gallery pursued property ownership as a means of long-term stability—or else be forced out of the rapidly gentrifying River West neighborhood. Though RSG was able to secure a downpayment on their building with the help of outside funding, their financial precarity reached a breaking point when Peter Taub left for the MCA in 1995. Unable to fund the salary of someone qualified to replace him, RSG inched toward collapse. By 1998, the gallery had reached an impasse, and decided to close its doors for good. Blackstone 2023

RSG’s legacy remains one of the most celebrated in Chicago’s history of artist-run spaces. Its massive archive (450 linear feet) of administrative records, publications, posters, ephemera, photographic documentation, video footage, and more has served as an indispensable tool to scholars, artists, and arts organizations alike.