Directions to the Zhou B Center:

Take the red line

Past Cermak-Chinatown,

At Sox and 35th.

Then, take bus 35 to Morgan.

Keep walking in the direction of the bus, until you see,

Two large red statues.

Walk between the statues

Towards the head relief of the Buddha.

You will find a car there, waiting.

Its ghost has escaped and is traveling

With an ensemble

As an ensemble

That is free.

While you are out at Sox and 35th,

Take a moment and listen to the cars

Speeding on the highway.

The car is driving on a highway.

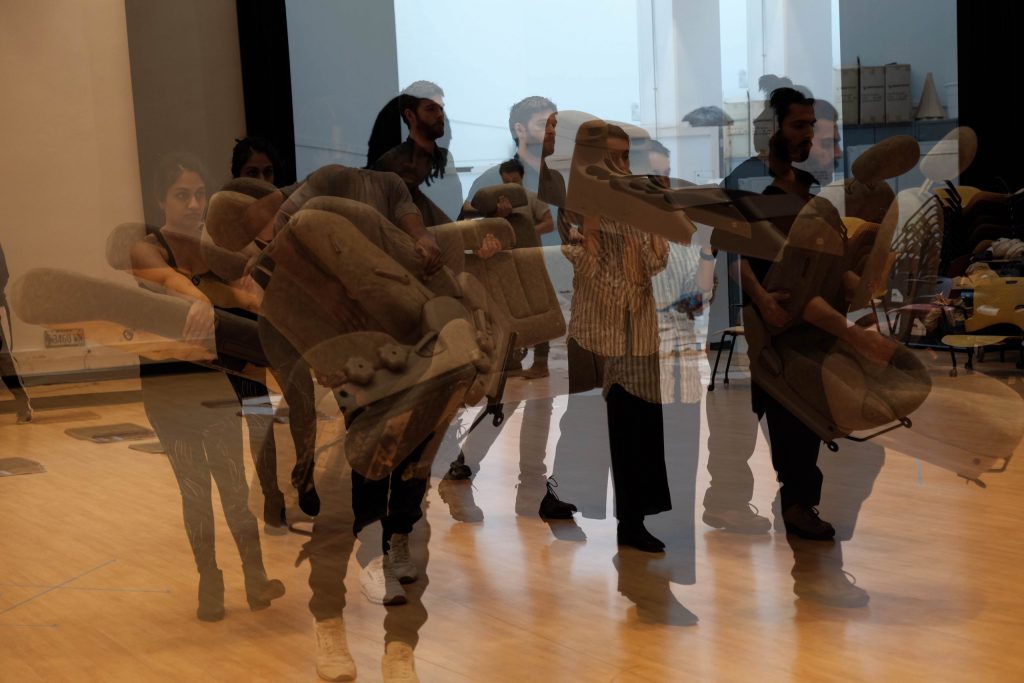

Members of the ensemble, like puppeteers, focus on the parts of the car they are holding, accompanying this floating ghost as it drives along, keeping the spirit of the car alive.

In order to achieve this, the performers will need to be able to lift objects (sometimes heavy) at a slow tempo for a long duration and place it back on the ground carefully without hurting themselves. Basic anatomy discussions and body mapping will prove useful, and some physical suggestions will be offered for body safety. Once the performers are ready to move comfortably while carrying large objects in slow tempo, ensemble movement will be emphasized. Through exercises of flocking, the ensemble may attune itself to its members, who will begin to widen their viewpoint and point of audition. Then, the ensemble may be able to move together as one car, safely.

In our training of slow tempo, we are taught the basics of walking, stopping, and turning around. The turn around is a deceptively simple gesture, which everyone will practice and explore. It is here where tempos are introduced not as metronomical, but as living, breathing timelines that should feel continuous: for instance, the head might move faster than the shoulder in the turn. Group turning, under flocking exercises will allow us to observe how the gesture travels in space across the ensemble from the source to the next person to the next person and so on, till the last person, turns and realizes they were the last person to receive the signal. The movement will be prolonged.

In this event, simultaneity is stretched out, and a natural travel of signal will unfold over time.

Then various forms of “explosion” will be tried and tested. By explosion, I essentially mean a fragmentation of the car and the ensemble into various parts of the room, splitting the room into two parallel opposing highways. Parts of the car will join and form other “cars” on the highway, moving in opposite directions. At this point, the audience can join the pedestrians.

Fragmentation leads to accidents. One by one, the core group may encounter traumatic memories either being involved in, or directly observing a car accident. These memories will be worked with, and acknowledged by the ensemble.

A soloist will be introduced in the “middle of the highway”, and groups of pedestrians begin walking along the highways in slow tempo.

Somewhere off in the distance, at a four-way intersection, four groups are ready to cross the street, or are perhaps crossing the street. One group of cars is usually waiting, while the other breaks off into a shoal and zooms past. It takes a while to notice that some people are crossing the street slowly, their slowness influenced by the flow of traffic signals. Somehow, an audience of strangers arranges itself in this cacophony. At the cue of a train passing by, the spare tire of a car enters the scene, making a cross. The pedestrians return to their normal walking pace.

The motivation/intent behind this project is to remember/piece together a dream — one that features my old beater car moving along on a long empty stretch at an ambiguous speed either 70 mph or at slow tempo, I cannot seem to remember which (the two are indistinguishable in my memory); slowly, however, the car “explodes”, and its various parts expand outward. (dream unfinished)

The content of my work is process-driven, beginning with a deconstruction of my automobile (auto = self, mobile = moving) and somewhat pataphysical reconstructions. The deconstruction began when my car finally broke down off the I-94 S (Dan Ryan expressway) on my way south to Urbana-Champaign. After trying everything I could to get it started again, I bushwhacked to the Red Line and went home, hoping that the Illinois State Troopers would tow it eventually but I was mistaken. I returned to the same spot the next morning and finally towed the car to a church near my house. After negotiating with my landlord, I struck up a deal to clean his garage (one that had been untouched for decades) in exchange for being able to use it for a month. In a week, my friend Luan and I pushed the car into the garage, and I finally began taking the car apart, moving my way inside out.

The strategy I employ in making the work mainly involves using my car as the primary source material for the work while recalling dreams and various memories of enduring long distance drives while working various odd jobs in the United States. I gathered an ensemble consisting of circus folk, puppeteers, dancers, musicians, and filmmakers to meet once a week to practice mundane “pedestrian” movements in slow tempo.

A collaborative protest, this slowing down, a public demonstration. What started off as a strange pursuit of a pataphysical vision soon began to find some historical context. The car symbol in conjunction with a rhetoric of speed reminded me of Futurism, guided by its obsession with speed/motion and technological advancement. I was aware that the car served as a Futurist symbol in early 20th century art and I slowly began to think of ways of acknowledging this connection within my work.

“Car: at Waveforms” involved a pedestrian who was crossing a street with her bicycle, and a car (operated by the rest of the ensemble) that was implied to be in motion. The car ensemble performs a single gesture over the course of 10 minutes: a slow knob turn of the radio, playing out of the speaker on the right, and a slow crossfade of a continuous sound work (a slow knob turn on the EMU analog synthesizer) playing out of the left speaker; a solitary wheel turning slowly, and an ambiguous driver/passenger smoking a cigarette; two camerapersons flank the two headlamps of the car, hand-cranking 16 mm Bolex cameras slowly. The theatrical set up was arranged in part to reference the car accident as outlined in the original Futurist manifesto, in which the author F. T. Marinetti swerves his car to avoid crashing into two cyclists — his car falls in a ditch, and he hallucinates a vision of Futurism. Strangely, while setting up for this performance, I had a sudden flashback of a memory from when I was in fifth grade: I met with an accident, I was run over by a car, whilst riding my bicycle. I remember the basketball court, destroyed. People talked about it, not knowing what had happened. None of us wanted to make it a serious matter.. I remember chocolates, and flowers. A card. I remember hearing the sound of skidding. I remember the car was blue. I remember my mother was there, it happened in front of her.

Slow tempo refers to the performance practice of Ōta Shogo and the Tenkei Gekijō theatrical company (1968-1988) in which the performers move very slowly. It is a concept distilled by Ōta from traditional Noh and Kabuki theater. Slow tempo is a passive form, revealing itself slowly over the course of a performance like a picture book revealing its contents one page at a time. Ideally, the performance may be in a public location, and will be short enough to perform at most one or two gestures in slow. The work will passively invite an audience to slow down and to experience reality in a tempo different from what it is so accustomed to. Spectatorship and audience participation in slow may prove to be difficult given short attention spans and growing impatience, especially if we consider the normalcy of cinematic illusion of rapid flickering frame rates, and an exponential desire for faster and more efficient processing for our computing units. Slow tempo does seem to have its strongest effect when realized as an ensemble, providing a greater sense of time dilation and allowing for a self-referential performer-audience feedback loop within the ensemble itself. Thus, ideally the work should hold ground by itself in a public space unless it is deemed unsafe and/or disruptive.