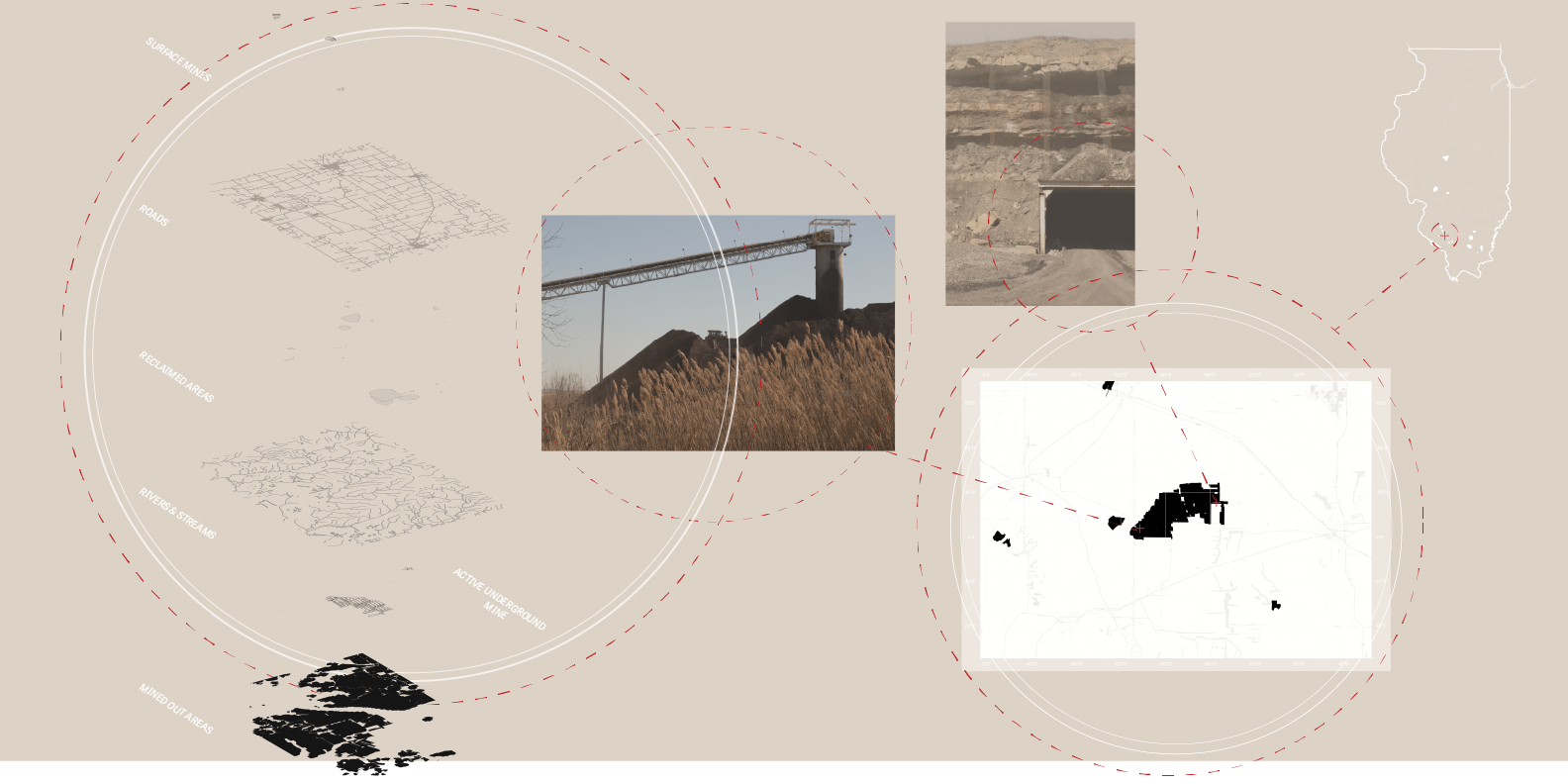

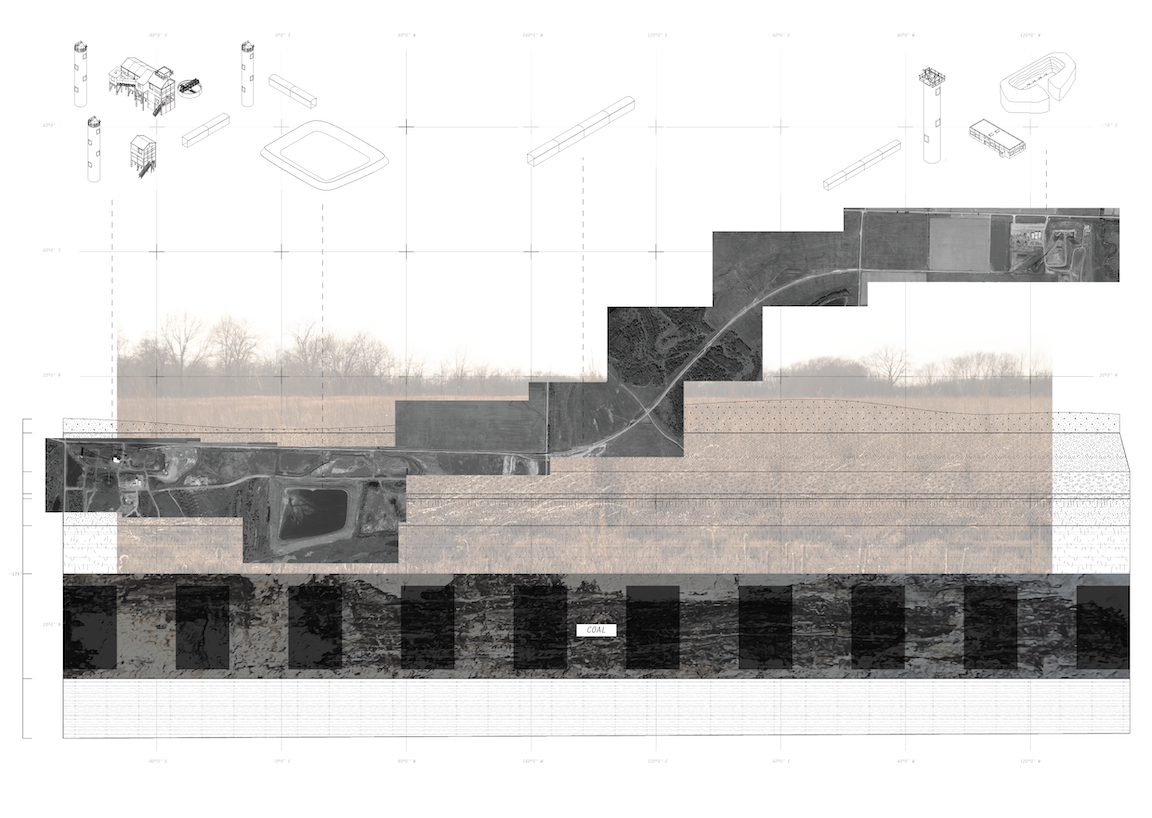

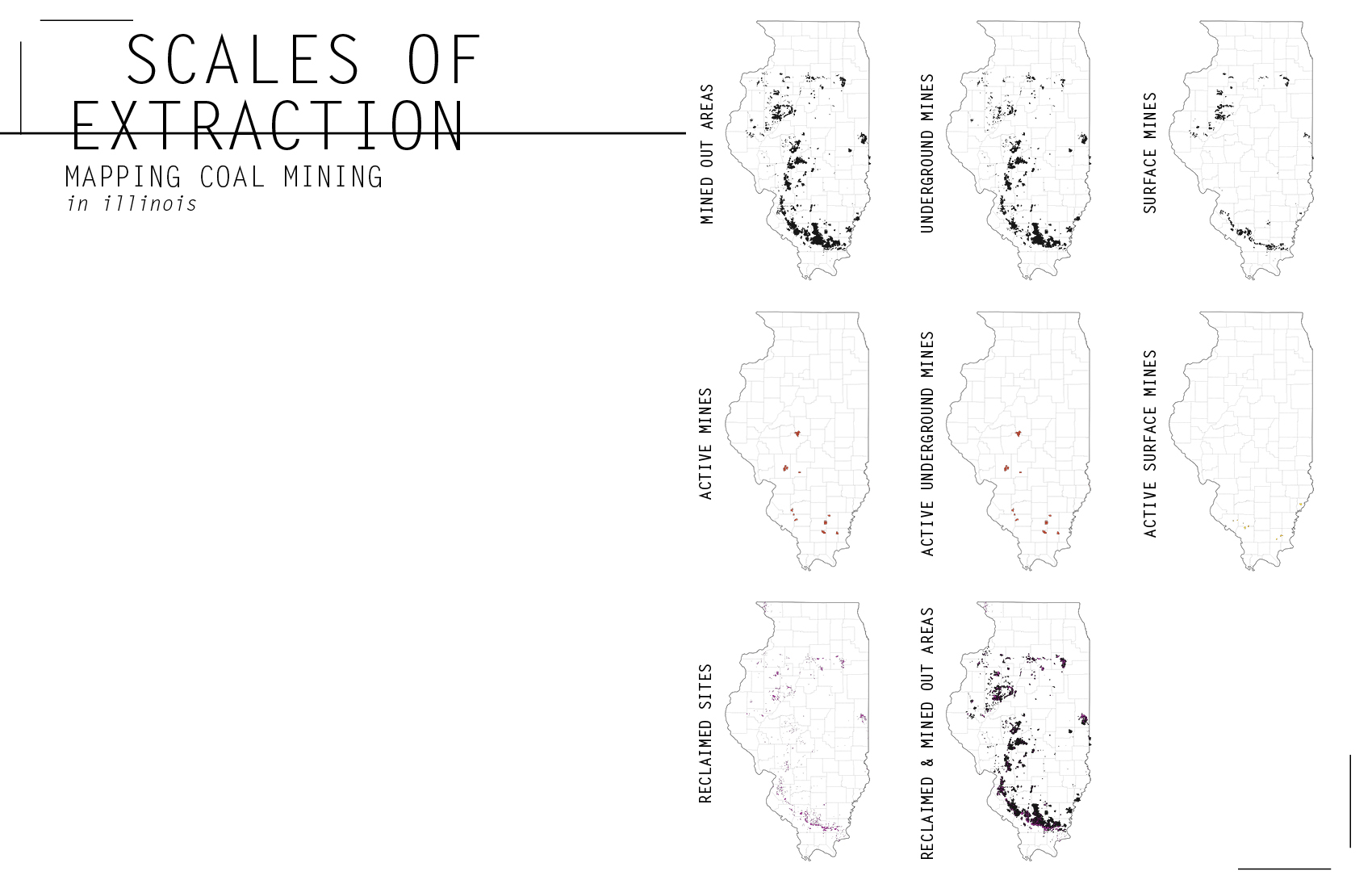

Coal was first discovered in the United States along the Illinois River in the early 1600s. By the 1800s, settlers had discovered coal’s economic value as an energy source and began extracting coal for commercial value. This discovery would set not only the state of Illinois but the entire nation on a nearly 200-year trajectory of extracting coal using exploitative processes with little to no restrictions or regard for environmental consequences. To date, nearly 1.3 million acres of Illinois’ prairie land has been mined out from underground and through surface coal mining.

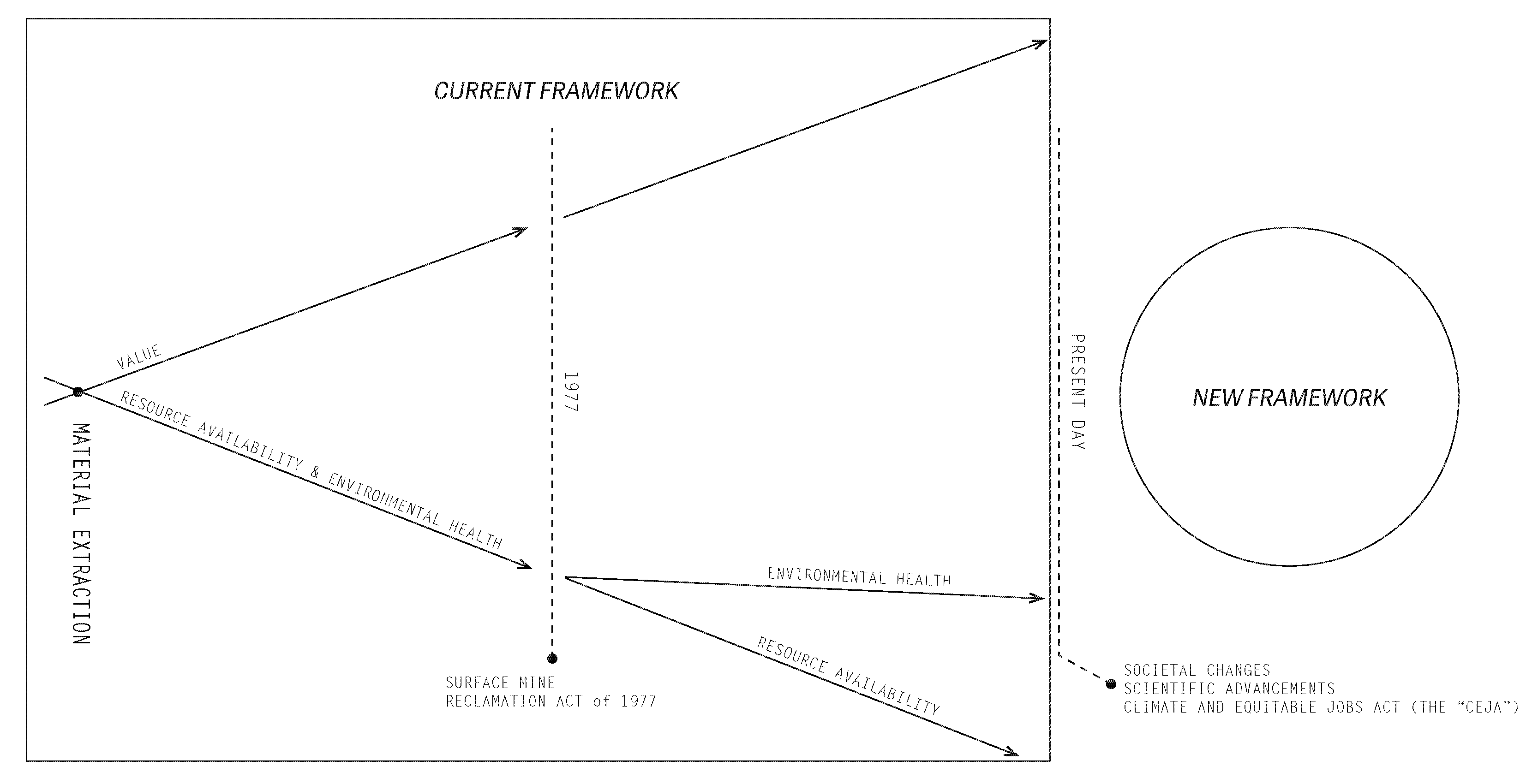

Out of growing concern for the environment, legislation was introduced in 1977 to help regulate active coal mines and help reclaim abandoned mines. This law enforces reclamation practices that have one singular focus—to return the surface level to their “pre-mined conditions”. This resulted in reclamation strategies that only conceal and camouflage the environmental cost of modernity.

Despite the global push to move towards clean energy, coal extraction is set to rise to its highest-ever levels in 2022. To truly transition away from the extractive economy that’s been built on coal will be a complex and lengthy process. This thesis explores future possibilities of a post-mining site—one that responds to both the visible industrial landscape above and the altered geology below while also honoring the memory of all that has been lost in this process.