Daedalus and Icarus take flight in Chicago: Insight into Roger Brown’s mosaic at 120 N. LaSalle St.

Saturday, November 10th, 2018 » By James Connolly » See more posts from Blogging the Archive, Staff Projects

Twenty seven years ago on a summer day in 1991, the Roger Brown mosaic at 120 N. LaSalle St. was unveiled. Standing confidently among Chicago’s portfolio of public art by famous artists – the Picasso, Calder’s Flamingo, Dubuffet’s Standing Beast, among many others – Brown’s two winged men soar high above the heads of pedestrians walking below on Chicago’s North LaSalle Street, across the street from City Hall. Against a brooding sky of dark clouds flecked with gold, the men appear to soar steadily upward, though those familiar with the tale of Daedalus and Icarus know what fate awaits the two men. Brown worked for almost two years to see the mosaic through to completion, beginning on the project while the building itself was still in the planning stages.

The property at 120 N. LaSalle St. has a modest history. Completed in 1891, an eight story office building was erected and called simply the Oxford Building. As in the building that occupies the site today, lessees were primarily law, architectural, financial, and real estate firms. The Oxford Building was demolished in 1935 to make way for a parking lot[1], at a time when the automobile was growing in popularity as an alternative and individualized form of transportation over mass transit.

120 N. LaSalle St. remained a parking lot until November 1989, when construction began on the current 40 story building in a project that would combine the functionality of the two previous developments, with the six bottom floors dedicated to parking, and the rest of the 390,000 square feet of rentable office space spread over the remaining 29 floors. The first project in Chicago by Los Angeles based developer Ahmanson Commercial Development, the building was designed by internationally renowned architect Helmut Jahn of the architectural firm Murphy/Jahn[2]. Jahn’s previous projects in Chicago included the 1982 addition to the Chicago Board of Trade as well as the Thompson Center, built in 1985. The building at 120 N. LaSalle remains a notable point of interest in the Loop not simply for its celebrity architect (Jahn is known for his flashy dress and demeanor), but also for its mosaic by our very own Roger Brown.

It was in late July 1989, before groundbreaking for the new building had taken place, when Brown was initially contacted about the possibility of a commission for the soon-to-be constructed building at 120 N. LaSalle Street[3]. Helmut Jahn was familiar with Brown’s work, as he had previously worked with George Veronda, Brown’s late partner, and had suggested Brown for the commission; Veronda and Jahn had been colleagues at the architectural firm of C. F. Murphy (of which Jahn later became a partner, forming Murphy/Jahn). Both Murphy/Jahn and the developer, Ahmanson Commercial Development Company, were supportive of Brown’s involvement with the project[4].

While at first deciding on the subject and overall feel of the mural, Brown took into account the building’s location, across the street from City Hall, where the mosaic would stand to greet the then Mayor Richard M. Daley and other local and state level politicians as they entered and exited city hall. Brown was cautious to avoid a subject that might feel dated with the passing of time; rather than make any direct commentary on current events or social issues, Brown sought a theme that would have the same impact in fifty years as the day it was created.

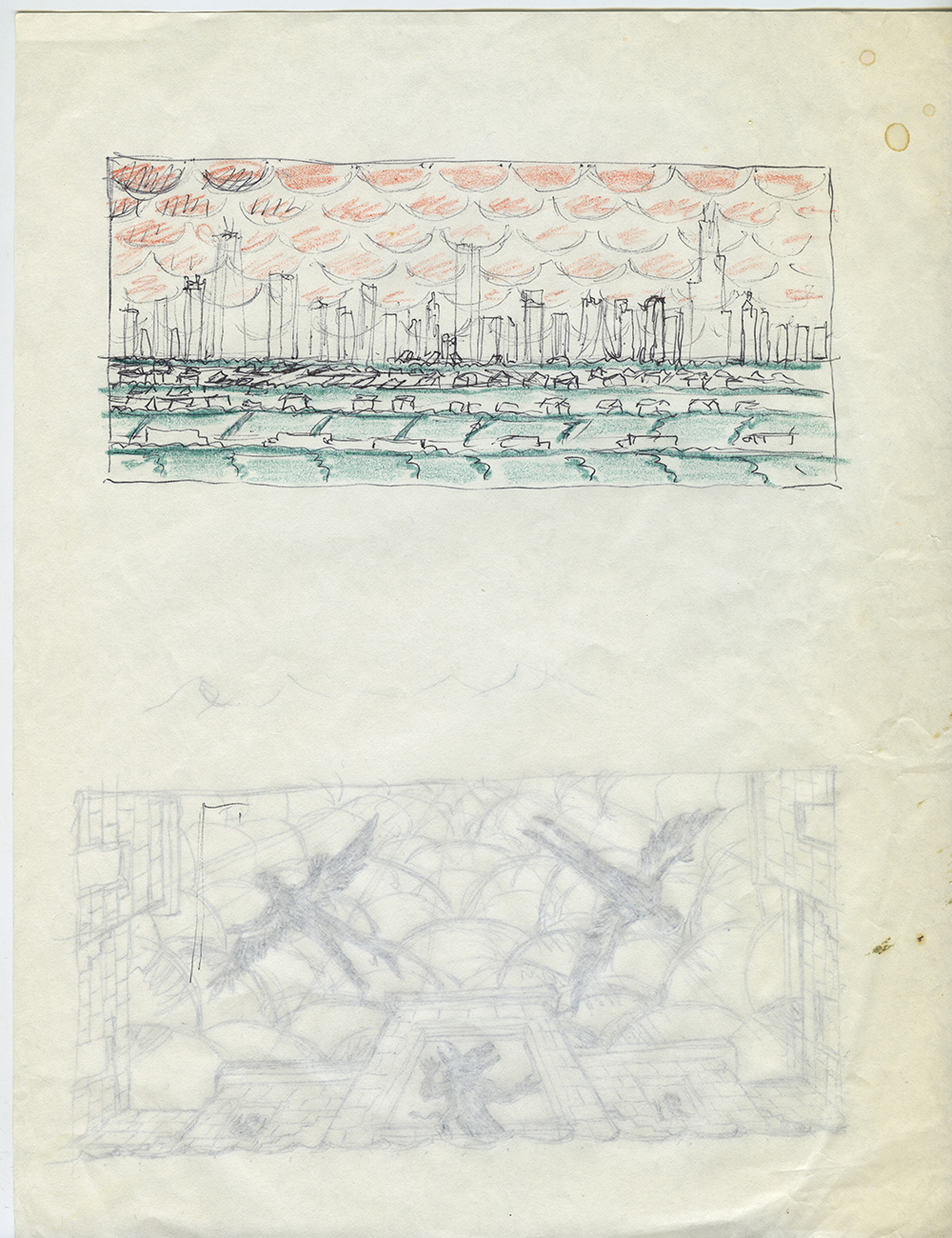

Figure 1: Roger Brown, “Untitled Sketch 05,” Pen on paper (n.d.), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

Brown felt the subject of the mosaic should both stand in context with and pay homage to Chicago’s rich architectural history. Initial ideas for the LaSalle mosaic featured the skyline of Chicago “rising from the ashes” of the fire (Figure 1), and share many similarities with City of Big Shoulders, another public commission Brown was working on at the same time (Figure 2). However in considering the concave ceiling upon which this mosaic would appear, high above the heads of pedestrians, Brown realized that incorporating imagery of the sky would be better suited for the location[5].

Figure 2: Preliminary sketches for City of Big Shoulders and the Arts and Science mosaics share the front and back of the page. Roger Brown, “Untitled Sketch 09,” Pen and ink on paper, (n.d.), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

In drawing connections between architecture and the sky, Brown came upon the tale of Daedalus and Icarus. The ancient Greek myth tells the story of Daedalus, the first architect, hired by King Minos of Crete to create a labyrinth that would contain the Minotaur. After a major event enraged King Minos and drove him to imprison Daedalus and his son Icarus on the island, Daedalus, ever the ingenious inventor, created wings of wax and feathers for him and his son so that they could take flight and escape the wrath of King Minos. Before their flight, Daedalus warned Icarus to “fly the middle path”—not too high, for the sun will melt the wax, and not too low, for the sea will wet the feathers, both resulting in failure. Ultimately, Icarus is so taken with the thrill of flying that he forgets his father’s advice and flies too close to the sun, melting his wings and plunging him into the ocean, where he drowns.[6]

Brown felt that this myth was an appropriate choice for the mosaic. Aware of Chicago’s lineage of corrupt politicians and nefarious innerworkings, Brown may have felt the tale’s cautionary stance against the perils of gloat and excess would be an appropriate image to greet politicians entering and exiting City Hall across the street. Brown also chose the tale for its celebration of technological innovation, where through grit and ingenuity Daedalus bestowed mankind with the gift of flight.[7]

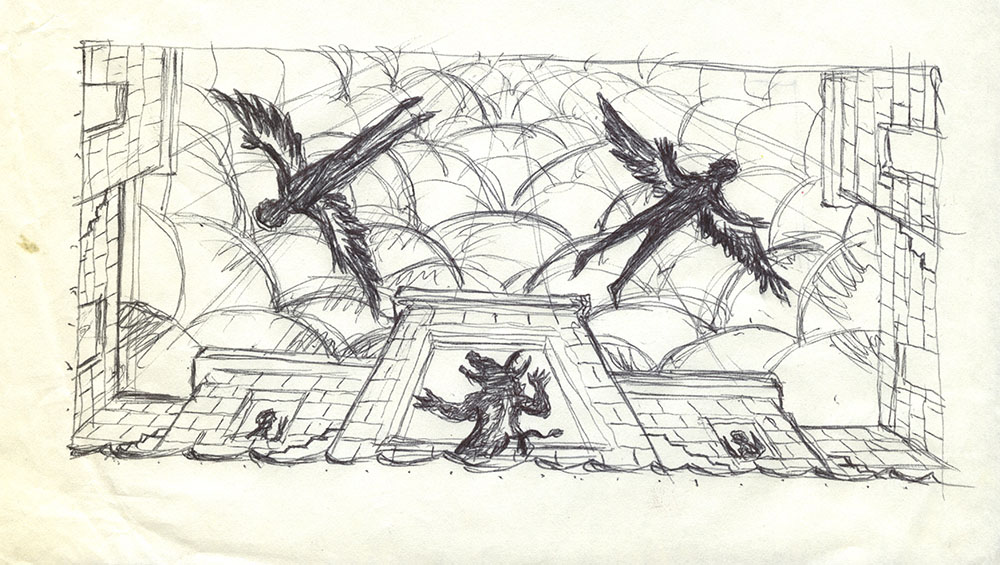

In beginning sketches for the LaSalle mosaic, color and composition varied greatly from sketch to sketch. Earlier drawings feature the failure of Icarus prominently, focusing on the precise moment when Icarus falls toward the sea. Several iterations of the sky were explored, with some versions featuring clouds in a dark red palette or dark dusty hues, and the direction of the clouds drifting downward in one, upward (as in the final composition) in another. In yet another sketch, the Minotaur threatens the mens’ escape (though the sequence of events would have been incorrect, as the reason Daedalus was imprisoned in the first place was because he aided Theseus in the defeat of the Minotaur). (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Roger Brown, “Untitled Sketch 09,” Pen on paper, (n.d.), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

Once Brown settled on his subject, the initial proposals featured two silhouetted figures set against a sky of patterned billowing clouds in Brown’s signature style (Figure 4). Brown was well-known for his use of black silhouetted subjects in the foreground (which usually included people with the likeness of his mother and father, animals, and/or elements of nature, like plants) against a patterned background – repeating clouds and rhythmically undulating landscapes are recurring motifs.

Figure 4a: Roger Brown, “Arts and Science of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus, modello in Red,” Oil on canvas, (1989), private collection.

Figure 4b: Roger Brown, “Arts and Science of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus, modello in dark colors,” Oil on canvas, (1989), SAIC Roger Brown Estate and Kavi Gupta. (click to enlarge)

Responses to the first round of sketches were that the mosaic was too dark – both formally and metaphorically. Out of concern that the message would be seen as too critical or too cynical, it was requested that the composition be changed to be more “uplifting” in tone. Brown bristled at the initial feedback. In a letter to a colleague, Brown reflects:

“By giving up the strong gradation from darkest to lightest and by giving up the silhouetting of the figures one level is being eliminated from the work. That level is the level of mystery. I realize now that what those people saw as ominous is what I see as mystery and perhaps for more people mystery is not an acceptable experience! …What they don’t realize is that it is the mystery and formal elements what is drawing them in, and the mystery is created by the effects of illuminating clouds, people, trees, and other content from behind – by not illuminating everything from the front and therefore not giving all the information. By doing this the viewer is forced to fill in some of the information himself.”[8]

Brown adjusted the tone and focus of the composition in response to the feedback. Additionally, after researching his subject further, Brown chose instead to draw upon Joseph Campbell’s commentary on Daedalus’s success and Icarus’s failure in his book History of Myth:

“For some reason, people talk more about Icarus than about Daedalus, as though the wings themselves had been responsible for the young astronaut’s fall. But that is no case against industry and science. Poor Icarus fell into the water–but Daedalus, who flew the middle way, succeeded in getting to the other shore.”[9]

Brown decided instead to highlight the beginning of the tale, just after the two men begin their flight. Interpreted as a moment brimming with hope and optimism, their flight is a celebration of science and technology, and the innovation that made such a feat possible. To accommodate the request of a more colorful and “illuminated” rendering of his subjects, Brown moved the light source to the front of the composition, illuminating both the foreground and background, rendering his subjects in full color (though, in Brown’s words, removing “the mystery” of the composition)[10].

Despite this turbulent start, Brown ultimately felt satisfied with the shift. He later wrote a colleague stating, “I loved doing the mosaic and I even think the initial process of compromise and changing the design was much for the better. I read recently that Louis Kahn did the same thing for Jonas Salk for the Salk Institute in La Jolla when Salk experienced an uneasiness with Kahn’s first design. So if Louis Kahn can do it and end up with a better design, so can I!”[11]

In the final composition, titled Arts and Science of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus, two men soar upward in unison into a sky of billowing clouds. Just above the reaches of the sea, the men appear steady and calm in their ascent. Devoid of any signs of movement (their robes lie smooth and creaseless against their bodies, their hair perfectly stiff), the figures appear to float against the sky, suspended. The tops of the clouds are flecked with gold, carrying the eye upwards and away from the dark sea below, casting a feeling of optimism on the overall composition. At the very right of the composition Brown designed a trompe l’oeil rendering of the H-shaped column that would stand in front of the mosaic once installed. In the final mosaic, the column is rendered using the same granite that clads the face of the building. The direct reference to the building on which the mosaic is installed gives the mosaic context and grounds this cautionary tale in the present moment, bridging the ancient and modern worlds. It also is a nod to its specific location, as if to say, this placement is not incidental. (Figure 5)

Figure 5: The final composition. Brown was especially careful to pay attention to detail in this painting as this would be the final image used by the mosaic studio to enlarge and reproduce in glass tesserae. Roger Brown, “Arts and Science of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus,” Oil on canvas, (1990), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

While the initial contract was for the design of the exterior mosaic, the project grew to include a smaller mosaic for the interior of the building. Titled Arts and Science of the Modern World: LaSalle Corridor with Holding Pattern, the smaller mosaic reflects the outdoor mosaic and again connects myths from the ancient world to reality in modern world. The mosaic itself is a stylized depiction of a modern-day view down the LaSalle street canyon, with the Chicago Board of Trade standing tall at the horizon. In this mosaic, Brown returns to his signature use of black silhouetted figures and simplified buildings rendered in various shades of cool grey. Set against the same sky where Daedalus and Icarus once flew, planes circle overhead waiting for their turn to land at O’Hare. The myth of human flight is now realized.

While the mosaics are a direct nod to Chicago’s legacy of architectural innovation, the works also contain autobiographical parallels to Brown’s own life and his relationship with his life partner, George Veronda (1941-1984), and can be interpreted as an ode to Veronda and the important role he played in Brown’s life. In Brown’s depiction of Daedalus and Icarus, rather than portraying a demonstrable age difference of a father-son relationship, the two men appear to be the same age, and decidedly similar in appearance. In discussing the mosaics (both of the winged men and airplanes in holding pattern) with Mary Mathews Gedo, psychoanalyst-turned-art historian and publisher of several books that employ a psychoanalytic approach to art criticism, Brown remarked that for him the two men “soaring away [served] as symbolic of our trips together”[12].

Veronda had an immeasurable influence on Brown’s own development as an artist, cultivating Brown’s interest in architecture. After all, it was through Veronda that Brown had become familiar with Helmut Jahn and his work. In Brown’s writing, For George: An Autobiography in Pictures, a memoir about time spent with his partner, Brown wrote, “George introduced me to the importance of Mies van der Rohe and to the style of contemporary Chicago architecture… and drew my attention to the importance of the pattern and repetition”.[13]

Through Veronda’s influence, Brown began to draw connections between the midwestern landscape and architecture. After a formative trip together to the Black Hills of South Dakota, the artist “began to treat landscape in an architectural manner, creating very formal patterns and placing cities, objects, and people within this setting”.[14] In Brown’s own words, “This observation [represented] an exciting expansion of my own work and became a dominating factor” in his art from that point forward.[15]

The mosaics were realized and installed by Crovatto Mosaics, a studio in Spilimbergo, Italy. Brown communicated closely with Constante Crovatto, head of the studio, to ensure a smooth interpretation of the design. In a letter to Crovatto, Brown insisted, “I prefer they have the quality more related to the earlier Italian “primitives” (so-called): Giotto, Masaccio (sic), Duccio, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca. I even look forward to the increased stylization which will inevitably result from the mosaic technique.”[16]

A team of six people took four months to complete the 27’ x 54’ mosaic[17]. Workers prepared the mosaic in sections, to be shipped overseas assembled on site (Figure 6). During this time, Brown flew to Italy for ten days near the end of the completion of the mosaic to conduct a final review of the project. Back in Chicago, a team of Crovatto employees were flown in for the installation and took three weeks to complete. The final exterior mosaic consisted of almost 1 million individual tiles.

Figure 6: Photos taken by Brown of the mural construction during his trip to Italy. (1991), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

The mosaics were unveiled on July 31, 1991 in a ceremony that was attended by friends, collectors, and local officials. Later that year, on November 12, 1991 the grand opening for the entire 120 N. LaSalle Building was held, almost exactly two years after ground was broken on the site (Figures 7, 8).

The mosaics at 120 N. LaSalle were the first of several public commission for Brown. Happy with his first experience working with Crovatto mosaics, specifically their successful translation of his style into the mosaic medium, Brown worked with Crovatto to complete two other public commissions, Twentieth Century Plague: The Victims of AIDS, completed in 1995 for the lobby of the Foley Square Federal Center in Manhattan, and another Chicago commission in 1997, Hull House, Cook County, Howard Brown: A Tradition of Helping, for the lobby of the Howard Brown Health Center.

Figure 7: Photo of mosaic as installed at 120 N. LaSalle Street. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

Figure 8: Photo of interior mosaic as installed in the lobby of 120 N. LaSalle Street. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

From the very beginning, the 120 N. LaSalle Building was steeped in Chicago culture. Both architect and artist were men of international stature who made a home and carried great influence in Chicago: Helmut Jahn, whose numerous architectural projects shape Chicago’s urban landscape (and will continue to shape the landscape as Jahn’s firm is still designing projects for the city), and Roger Brown, among the most celebrated and well-known Chicago artists. Brown’s contemporary use of classical subject matter fits in with Chicago’s collection of classical revival style architecture, and marries the contemporary moment with the past, situating 120 N. LaSalle Street comfortably within Chicago’s portfolio of public art and lineage of distinguished architecture.

Alessandra Norman, 2018

[1] Steve Kerch, “Apartments Hold Investment Allure”, Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1992

[2] Ahmanson Commercial Development Company, “Installation Of Roger Brown Mosaic At 120 North Lasalle Street Adds To City’s Public Art Collection”, News release, Chicago, IL, July 31, 1991, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_009_003

[3] Tamara Thomas, “Thomas To Brown: July 31, 1989”, Letter (1989), Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago

[4] Thomas, “Thomas to Brown: July 31, 1989”

[5] Andrew Gottesman, “Pieces Fall Into Place For Craftsman”, Chicago Tribune, August 02, 1991.

[6] Edith Hamilton, Mythology, 14th printing, (New York: 1961), 139-40 and 151-2, as referenced in Mary Gedo, “Public Art/Private Iconography: Roger Brown’s Transformation Of The Myth Of Daedalus And Icarus”, Art Criticism 11, no. 2 (1996): 53.

[7] Roger Brown, “Untitled Notes”, Notes, (n.d.), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_003_003.

[8] Roger Brown, “Brown to Thomas”, Letter, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_001.

[9] Mary Gedo, “Public Art/Private Iconography: Roger Brown’s Transformation Of The Myth Of Daedalus And Icarus”, Art Criticism 11, no. 2 (1996): 41.

[10] Brown “Brown to Thomas”

[11] Roger Brown, “Brown to Thomas”, Letter, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_003.

[12] Roger Brown, “Brown to Gedo”, Revisions/annotations to text by Gedo, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_010_007.

[13] Roger Brown, “For George” (unpublished memoir), transcription of hand-bound book on Arches paper, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago: 2.

[14] Brown, “For George”: 2.

[15] Brown, “For George”: 3.

[16] Roger Brown, “Brown to Crovatto”, Letter, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_002. *my best guess, handwriting was difficult to discern

[17] Gottesman, “Pieces Fall Into Place For Craftsman”

Bibliography

Brown, Roger. “For George” Unpublished memoir, transcription of hand-bound book. Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Brown, Roger. Letter from Brown to Constante Crovatto, 1990. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_002.

Brown, Roger. Letter, attachment with revisions/annotations to text originally by Gedo from Brown to Mary Gedo, 1990. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_010_007.

Brown, Roger. Letter from Brown to Tamara Thomas, 1989. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_001.

Brown, Roger. Letter from Brown to Tamara Thomas, 1989. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_003.

Brown, Roger. Miscellaneous notes on the LaSalle mosaic. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_003_003.

Gedo, Mary “Public Art/Private Iconography: Roger Brown’s Transformation Of The Myth Of Daedalus And Icarus”, Art Criticism 11, no. 2 (1996): 41.

Gottesman, Andrew. “Pieces Fall Into Place For Craftsman.” Chicago Tribune, August 02, 1991.

Hamilton, Edith. Mythology, 14th printing, (New York: 1961), 139-40 and 151-2, as referenced in Mary Gedo, “Public Art/Private Iconography: Roger Brown’s Transformation Of The Myth Of Daedalus And Icarus”, Art Criticism 11, no. 2 (1996): 53.

“Installation Of Roger Brown Mosaic At 120 North Lasalle Street Adds To City’s Public Art Collection”, News release, Chicago, IL, July 31, 1991, Ahmanson Commercial Development Company. Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_009_003.

Kerch, Steve. “Apartments Hold Investment Allure.” Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1992.

Thomas, Tamara. Letter from Thomas To Brown, 1989. Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_001_001.

Tags: Alessandra Norman, Roger Brown