Thursday, September 11, 6pm | Restored 35mm blow-ups!

Joyous, restless, audacious and witty, Robert Breer’s animated films are like no others. Time and again Breer marries his playful perspective to cutting-edge techniques to create formally innovative, non-narrative films filled with humor and charm. Tonight’s program features a selection of sparkling new 35mm blow-ups, including Breer’s rapid-fire collages (Blazes, 1961; Fist Fight, 1964), gentle line drawing exercises (A Man and His Dog Out for Air, 1957), formal geometric abstraction (69, 1968), and films combining representational action with stylized drawing and fractured continuity (Fuji, 1974; Swiss Army Knife with Rat and Pigeons, 1981). Also featured are Eyewash (1959) 66 (1966), 70 (1970), 77 (1977) and Bang! (1986). Preservation by Anthology Film Archives, with the generous support of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. Image courtesy Anthology Film Archives. 1957—86, Robert Breer, USA, 35mm, ca 70 min.

——

A Man and His Dog Out for Air

1957, 35mm, 2 min.

A funny, farcical line animation. This film was shown as a short before Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad during that film’s initial NY theatrical run.

Eyewash

1959, 35mm, 3 min.

A dizzying array of images flows like water on the screen. Breer hand-painted each print, adding color into particular sections to create different levels of texture.

Blazes

1961, 35mm, 3 min.

“100 basic images switching positions for four thousand frames. A continuous explosion.” (RB)

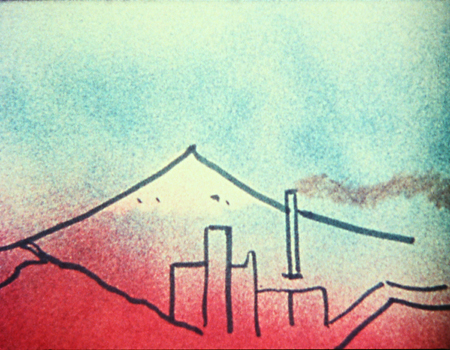

Fuji

1974, 35mm, 9 min.

“A poetic, rhythmic, riveting achievement…in which fragments of landscapes, passengers, and train interiors blend into a magical color dream of a voyage. One of the most important works by a master who – like Conner, Brakhage, Broughton – spans several avant-gardes in his ever more perfect explorations.” -Amos Vogel

66

1966, 35mm, 6 min.

“Abstract, quasi-geometric study in interrupted continuity.” (RB)

69

1969, 35mm, 5 min.

“It’s so absolutely beautiful, so perfect, so like nothing else. Forms, geometry, lines, movements, light very basic, very pure, very surprising, very subtle.” -Jonas Mekas

70

1970, 35mm, 5 min.

“Made with spray paint and hand-cut stencils, this film was an attempt at maximum plastic intensity…

[P]laces Breer for the first time among the major colorists of the avant-garde.” -P. Adams Sitney

77

1970, 35mm, 7 min.

“Breer is a consummate master of cinematic space. Like Hans Richter, he constantly provokes a sense of depth through changing the scale of his shapes.” -Noel Carroll

Fist Fight

1964, 35mm 9 min.

Created as a component of Allan Kaprow’s 1964 staging of the opera Originale by Karlheinz Stockhausen which featured Charlotte Moorman and many of NYC’s other avant-garde luminaries.

Swiss Army Knife with Rat and Pigeons

1981, 35mm, 7 min.

“Displays sinuous cutting between live action and animated images, rapid-fire associations and transformations, freedom in collaging the everyday with the imaginary in sound and image, and a diabolical moment of synthesis at the climax when the rat trap is sprung.” -Amy Taubin

Bang

1986, 35mm, 10 min.

“Breer sustains ten dense minutes of collagistic mayhem that’s as potent as anything he’s ever done. Television images of a boy paddling a boat and an arena crowd cheering, plus filmed shots of bright pink flowers and a toy phone with the receiver off the hook, are intercut with frenetic drawings in Breer’s trademark heavy crayon, principally of baseball games.” -Katherine Dieckmann

——

Robert Breer’s career as an artist and animator spans over four decades, from paintings and early flipbooks to kinetic sculptures and his seminal animated films. He entered film through painting in the early 1950s when he was living in Paris and deeply influenced by Neo-plasticism as defined by Mondrian and Vasarely. Breer channeled his interest in geometric abstraction into his remarkable first group of films, Form Phases (1954-1956), which explored the role of movement in the understanding of form and space. Breer’s wonderful kinetic sculptures also tie directly into the concern for movement, composition and space perception which has remained central to his films. Combining a meticulous attention to form and rhythm with an acerbic wit and talent for satire, Breer provides an important link between the abstract films of Richter, Eggeling and Leger and the lyric and radical traditions of the avant-garde, from Brakhage and Baillie to Kubelka and Sharits. (Biography courtesy Harvard Film Archives)

More