Tomorrow Wayne Boyer, Michael Golec, Associate Professor of Design History at SAIC, and Anne Wells, Collections Manager for the Chicago Film Archives (CFA) will join us at the Gene Siskel Film Center post screening for a round table discussion. This week Anne Wells of the CFA writes for us, reflecting on her personal relationship with the filmmakers as she also re-introduces and premiers their highly innovative and visually stunning work.

I first came to know Wayne Boyer and Larry Janiak through Chicago Film Archives’ Mort & Mille Goldsholl Collection, which contains over a hundred industrial films made by the Chicago-based design firm, Goldsholl Design & Film Associates. Both Boyer and Janiak worked for the firm in the 1960’s and played a significant role in shaping the look of their playful sponsored films. I didn’t get a full understanding of Boyer and Janiak’s fierce experimental vision for film until CFA acquired Janiak’s films in 2011 and Boyer’s in 2015.

Wayne and Larry share strikingly similar biographies. Both were born in Chicago (Wayne in 1937 and Larry in 1938), attended the same high school and college (Lane Tech High School and the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology), worked at the same Chicago-based design firm (Goldsholl Design & Film Associates), helped found an artist-run film co-op (Center Cinema Film Co-op) and went onto teach and develop art programs at Chicago universities (Wayne at University of Illinois at Chicago and Larry at IIT).

Their biographies first converge in the early 1950’s in the hallways of Lane Tech High School, where the two collaboratively made their first films–the first such films ever made by students in the Chicago Board of Education system. The two later honed their filmmaking skills at the Institute of Design and then at Goldsholl Associates, two environments steeped in Bauhaus traditions.

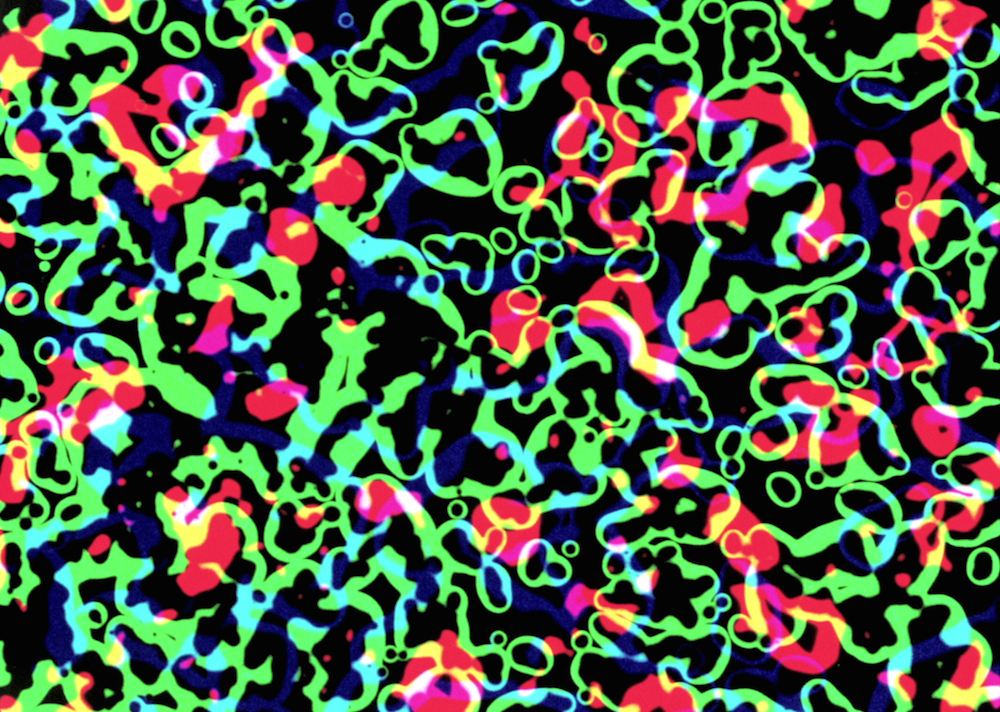

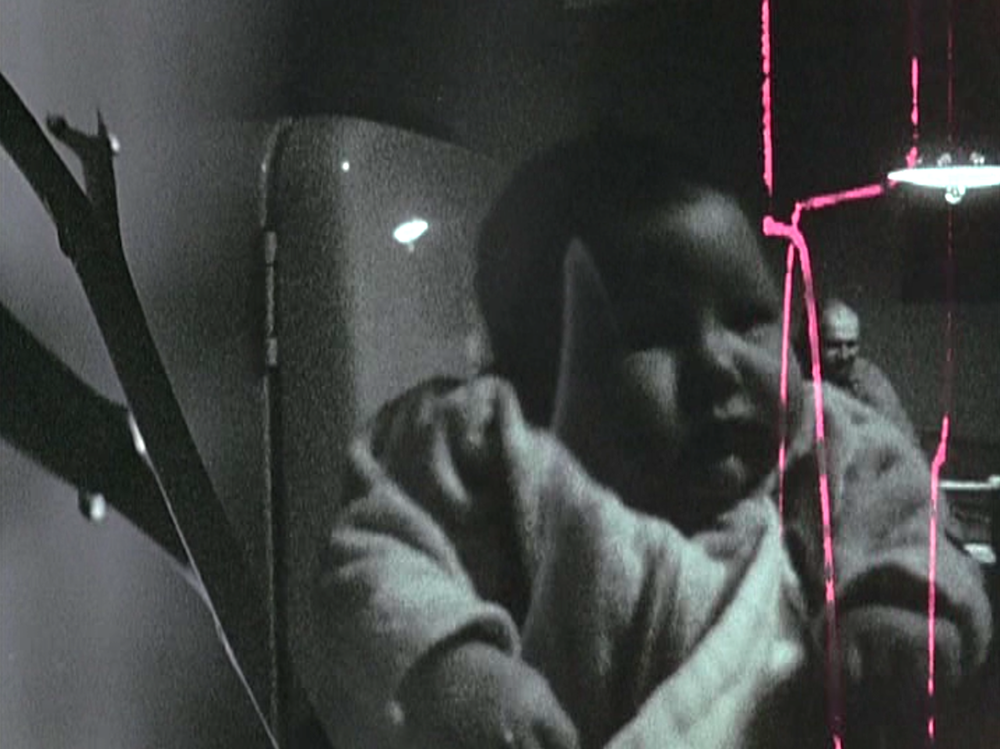

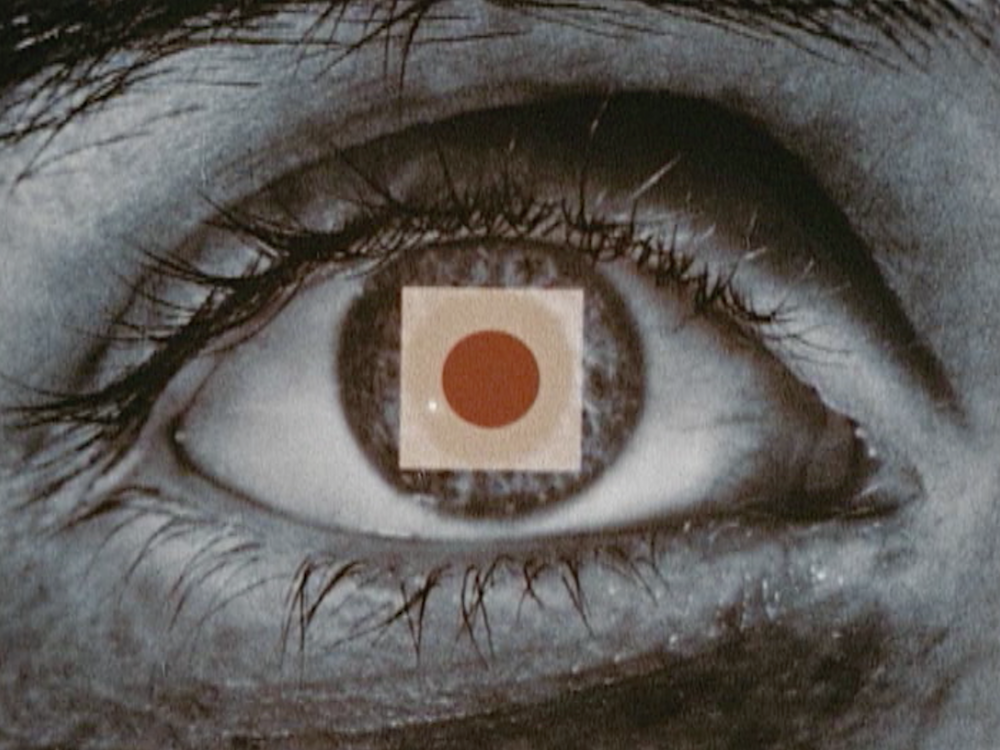

But despite these similarities, their styles and filmmaking techniques are unmistakably distinct. As our concise blurb states, Wayne explored visual abstraction via technical mastery and appropriation, while Larry utilized direct animation techniques and personal fragments of everyday life. The subjects and moods of their films also differ. Boyer’s work approaches historically rooted subject matter with unbelievably precise skill, while Larry’s work reflects his own quest for meditative transcendence through both unfamiliar and familiar imagery.

I’ve been working with Janiak’s films for a few years now and I’ve begun to connect with them in a deeply personal and emotional way. A lot of this has to do with the delightful conversations I’ve had with the very private Larry over the years, but also from the indescribable places that Larry’s films seem to take me. His films are both emotional and physical for me. I feel them in my gut.

I’ve only just started to work with Boyer’s oeuvre. I find his films to be similarly emotional and absorbing, but due to their more defined subject matter, they transport me to more specific times and places. The structures Wayne documents–the Chicago Stock Exchange Building and Drop City, for example–are no longer with us. Through this loss, his films gain further significance by granting us the opportunity to just simply experience these past environments.

The one for-hire work presented in this screening–Faces and Fortunes (1959)–presents an early example of both of their styles within a very unique commercial framework. As a filmic treatise on corporate identity, Faces and Fortunes explores the legacy and importance of “personality” achieved through the branding practices of industries, organizations and companies. Through the inventive use of live action, animation and optical techniques, this Kimberly-Clark sponsored film stands out as a stellar example of the industrial film genre. We see Wayne’s hand through the film’s innovative use of superimposition and Larry’s through the film’s spirited drawings and direct animation.

This screening is not just a re-introduction of these two artists to new audiences, but also the premiere of newly restored film prints funded by the National Film Preservation Foundation. We are so delighted to share these prints with Chicago audiences for the first time, and in general, excited to screen all of these titles on their native format–16mm.

Chicago Film Archives is a regional film archive dedicated to identifying, collecting, preserving and providing access to films that represent the Midwest. Our purpose is to serve institutions and filmmakers of this region and elsewhere by establishing a repository for institutional and private film collections; serve a variety of cultural, academic and artistic communities by making the films available locally, nationally, and internationally for exhibition, research, and production; and serve our culture by restoring and preserving films that are rare or not in existence elsewhere.