Tomorrow English filmmaker Louis Henderson will join us for his first Chicago appearance! Video Data Bank‘s Lindsay Bosch blogs about Henderson’s references to the Internet and computing in his complex meditations on neo-colonalism and contemporary Ghana.

Most of video art I watch, I watch on my laptop. I dream of creating a perfect screening space—uninterrupted hours, big screen, dark room—but can never fully realize it in the rush of the day. Of course, when I watch on my computer screen, the Internet is in the background, pulling me in and intruding on the images. Messages pop-up, emails ding and news alerts assert themselves, pushing against my screening experience. The thump and whir of the world is always there, behind the screen, dragging me away. I feel guilty about this, knowing that my full attention is required, believing that I should be cut off from the world to view correctly.

When I first began watching Lettres du Voyant (2013) by Louis Henderson I was (as always) on my computer… As this complex work unfolded, I allowed myself to give in to the pull of the technological. (Ok Google: Where is Agblogbloshie?). The artist’s documentary-fiction about contemporary Ghana invites a continued search for information, welcoming Internet deep dives into the beautiful and the strange practices it introduces. Henderson thrives in the grey area between fiction and non-fiction, calling forth (but not satiating) our desire for information on his subject.

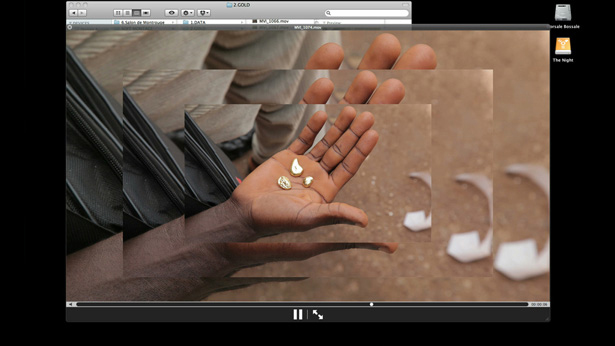

“I can move over and beyond national boundaries…Through the sub ocean Ethernet cables… I haunt the technological” recounts Voyant’s nameless narrator. Henderson’s practitioners of Sakawa Internet scams resist neo-colonial power by reaching out through their digital connections. While viewing Voyant, I paused it to reach back through the same digital portals to learn about this new subject. (Ok Google: What is is Sakawa?) Henderson himself has discussed how his process of discovery begins online: “My location scouting always begins on the internet, with Google images and Google maps.”

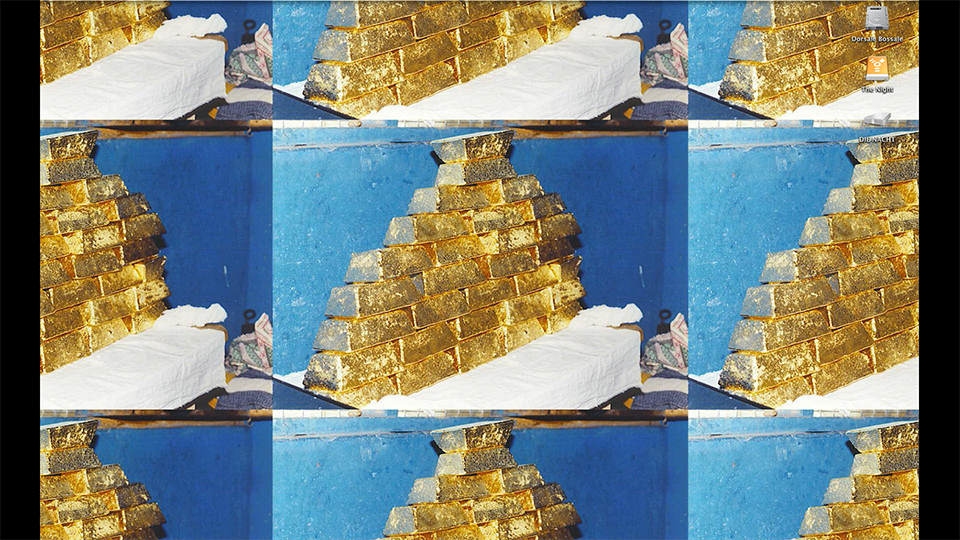

We are all together, then, in these sub ocean connective cables: viewer, filmmaker, and subject each moving toward each other. The recurring digital images of golden tunnels, mines of gold and mines of information, connect scenes to each other, and make this metaphor material. Henderson’s work in Lettres du Voyant and the desktop-documentary All that is Sold (2014) both introduce careful ethics and poetic beauty into the documentation of a complex, post-colonial African history. The artist’s digital alchemy allows for the fact that, most often, it is through the technological that we encounter the world, and that it encounters us.

“We have to work to make ourselves visionaries,” notes Voyant’s narrator. Henderson allows himself (and his viewers) to give in to that “thump and whir” of the digital, to reach beyond and through the screen itself to confront the “rubble of history” where we find it. Throughout his practice, Henderson demonstrates new ways to use our mediated tools to dive deeply toward the fascinating, the complex, and the foreign. We need to be connected to the world, not cut off, in order to view his work correctly.

Lindsay Bosch is the Development and Marketing Manager at the Video Data Bank. Founded at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) in 1976 at the inception of the media arts movement, the Video Data Bank (VDB) is a leading resource in the United States for video by and about contemporary artists. The VDB Collection includes the work of more than 550 artists and 6,000 video art titles.