This week we are thrilled to present the animated films of Suzan Pitt! I am excited to welcome SAIC art history graduate student Lara Schoorl to the blog. Schoorl reflects on the psychosexual nature of Pitt’s films while describing their visually stunning style.

Suzan Pitt’s films from the 1970s through the 2010s show us dream worlds, female desire, depression, sexual fantasies, the beauty of nature, and its destruction. They share with us a human lust for life that is both beautiful and annihilating. Influenced by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung and the liminal spaces between dream and reality, consciousness and unconsciousness, inside and outside, Pitt’s films have a stimulating and layering effect, yet one that never reaches climax. Moments don’t end; instead, they hover and continue to begin. This evokes a feeling of being between waking and dreaming–never completely one or the other. This interstitiality is reinforced by Pitt’s quivering, hand drawn lines–characteristic of the techniques of cel and stop-motion animation she uses.

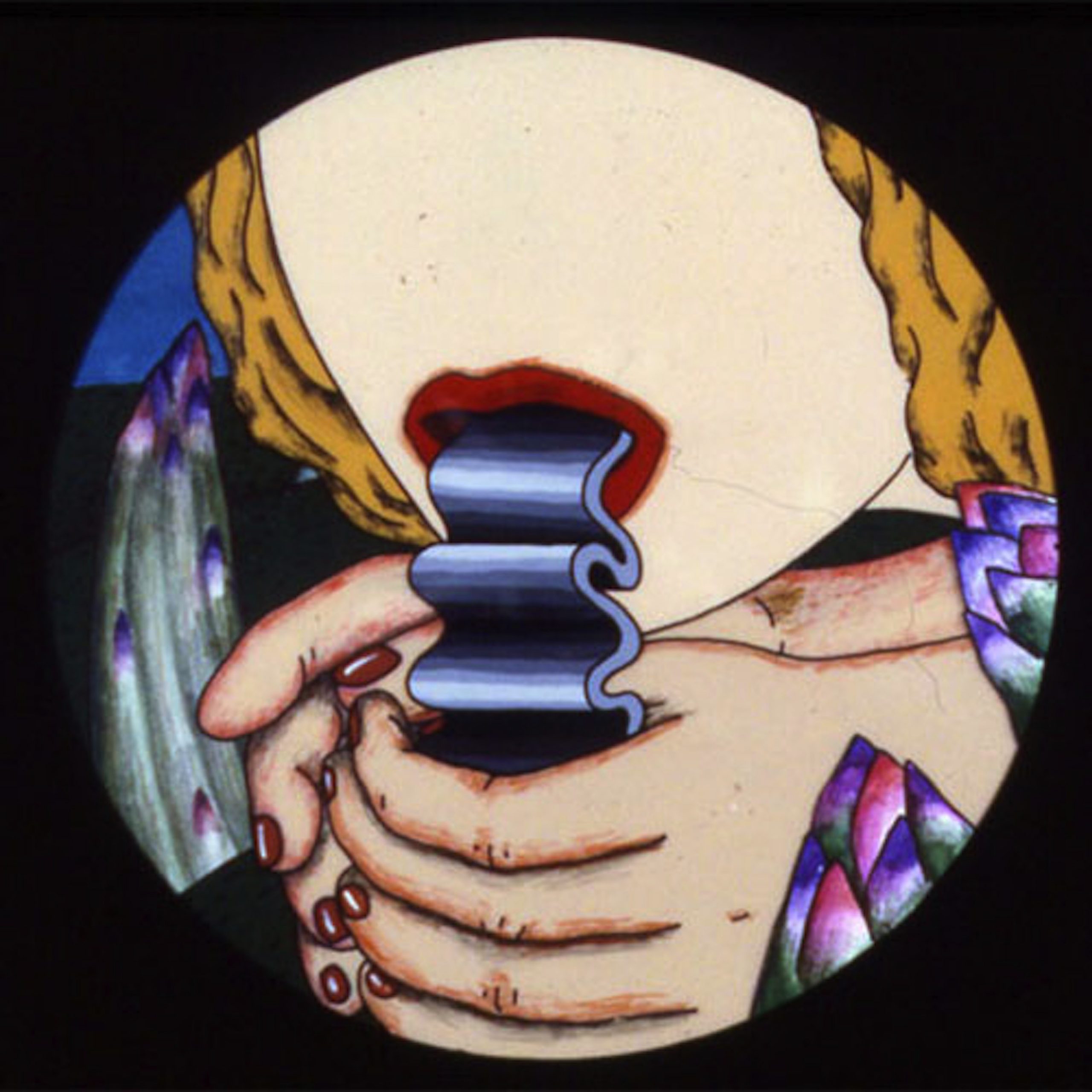

Suzan Pitt is a painter and an animator, and as such she draws and hand-paints each cel of her cel animations, which literally bring her touch into her films. In Asparagus (1979), her most famous film, and one of the five shown this week at Conversations at the Edge, the viewer follows a woman without a face who follows her own psyche and desire. In colorful and trembling scenes she wanders through the spaces of her home, her mind, and a theatre where she sees, creates, touches or transforms vulval and phallic shapes. The unfurling of images–of the woman excreting asparaguses, of the woman seeing a large hand caressing an asparagus in the flamboyant garden outside, of the woman looking at a miniature of her own house, of the woman as the only drawn figure in a claymation theatre stepping on stage and unleashing dreamy shapes from her purse, and finally, of the woman fellating a shape-shifting asparagus–have a mise-en-abyme-like effect. Scenes unfold and fold back into each other. We look at a woman looking inside herself; we look inside ourselves. At least I do.

A more recent film, Pinball (2013), shows a frenetic composition of images and music, which causes corollary associations to erupt. A whirlwind of colors, geometrical shapes and of figures moves to theatrical music. The result is reminiscent of early cartoons, opera, dance, perhaps of Interbellum modernism. Although the images are paintings by Pitt herself, some of the formal qualities resemble the work of, for example, Vasily Kandinsky, whose paintings also investigated the spiritual. The film is a visualization of the 1952 revision of George Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique, originally composed in 1924 to accompany a film by Ferdinand Léger. In Pitt’s interpretation of Antheil’s score, spinning movements and music suck the viewer in and toss around myriad associations, changing, morphing, and ricocheting off each other.

The fantastical, but recognizable, images in Pitt’s animated films invite the viewer to wander to where it leads you, to what you long for. Longing is the feeling that moves through Suzan Pitt’s animations, longing is what her films make me feel.

Lara Schoorl is currently pursuing a Master of Arts in Modern Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her research and writing concern narratives of contemporary art, translation theories, and more recently different understandings of the concepts of language, space, distance and love in poetry as well as visual art in the baroque and now. To approach her academic interests from a creative and subjective perspective she co-founded and is involved in collaborations with the Amsterdam Writers’ Guild, Potluck Salon and an experimental class called Shadows of Desire.