This week, we are excited to welcome graduate student, Julia Sharpe, to write for us! In her essay, Sharpe reflects on Jenny Perlin’s The Perlin Papers, an unsettling exploration of the United States’ culture of paranoia during the Cold War.

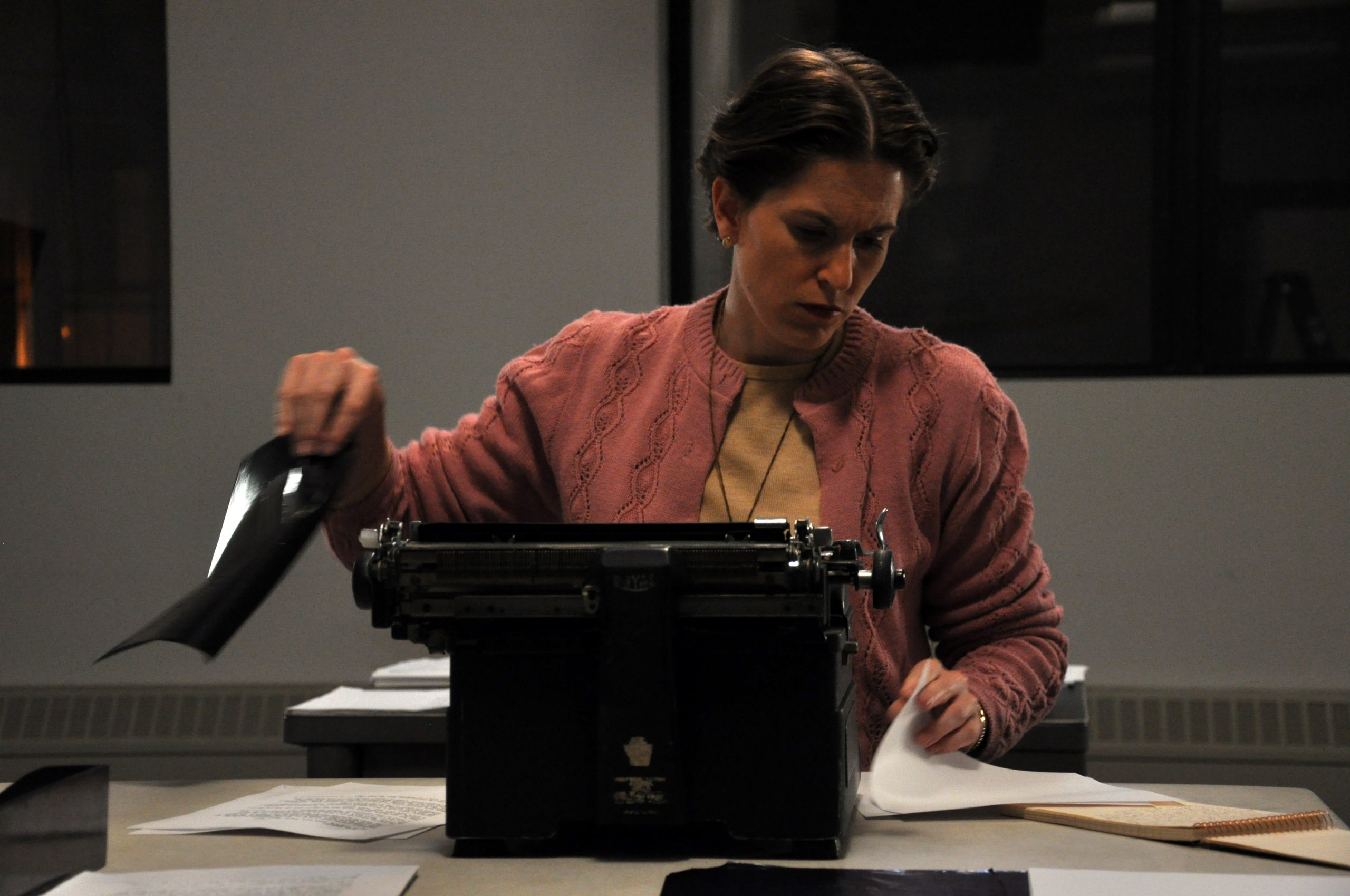

Jenny Perlin’s The Perlin Papers is an archive at Columbia University of declassified FBI documents on nearly 200 people peripherally related to the trial and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in the early 1950s. The first six films of this series reconstruct transcripts, recordings and hand-written materials from the archive. The seventh film is the fictitious depiction of two female transcribers at their desks. The eighth film is surveillance footage of a storage warehouse. As Perlin states at the beginning of the series, the films search around the “edges of the main story, unknown names, forgotten records, bad copies, scraps and bits.” Through the exploration of these mundane, bureaucratic and incomplete records, Perlin highlights the problematic nature of both surveillance and the archive; both are created in a context that allows for a specific interpretation of the materials gathered within it. That is to say, materials gathered under suspicion seek out the suspicious and therefore find the suspicious.

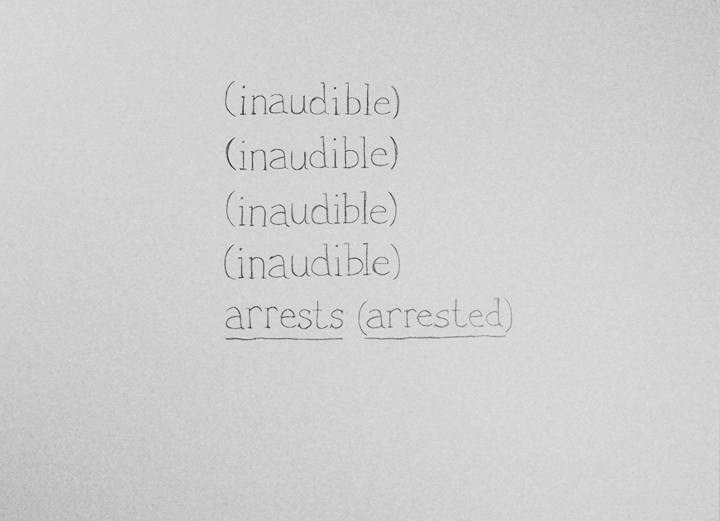

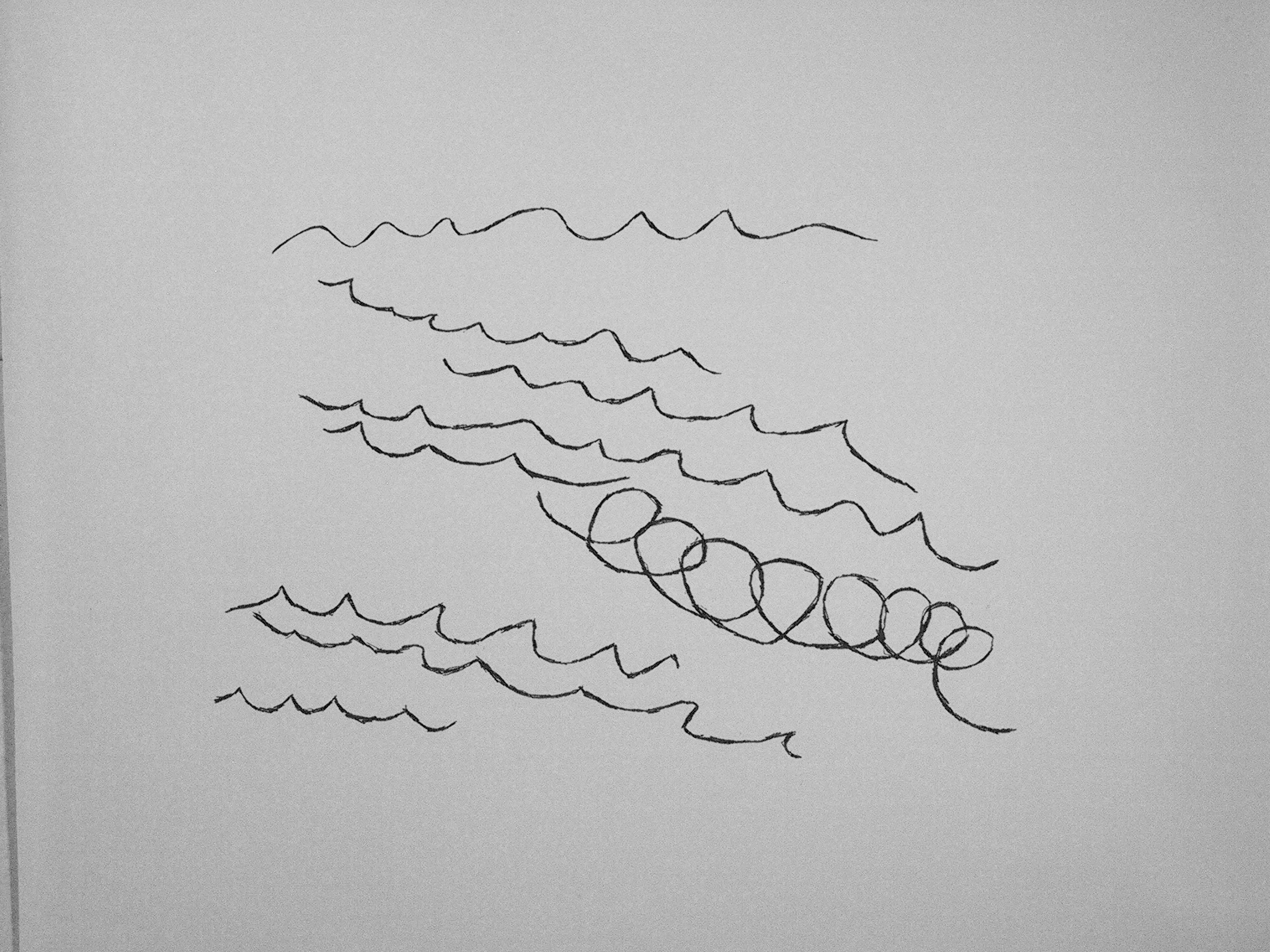

The fourth film in the cycle reenacts a transcript and recording from a 1953 dinner party, demonstrating this pattern. We listen in on the conversation from outside of the dinner party apartment. The camera moves from the entrance to the building up to the door of the apartment. We get close to the people speaking, but we never see them. At times, it is difficult to hear what they say. We hear words like “committee,” “meetings” and “witnesses.” But we also hear muffled sounds. When this scene closes, the voiceover notes, “the informant fills in words he cannot understand.” The fifth film shifts to the writing of this transcript, which appears as a vocabulary list because the most common word is “inaudible”—an indication that the informant cannot hear what is being said. The focus on this inaudibility calls the rest of the transcript into question. By emphasizing this unreliability, Perlin leads us to see that when taken out of context words can be used to reinforce a certain interpretation. In this way, the dinner party becomes self-fulfilling. Because the informant is looking for certain words, the informant finds them. The atmosphere of this reenactment displays an aspect of surveillance and the archive that are often unaccounted for in the legal system. Both are prescriptive; both are curated interpretations. In order for each to exist, there must be a set of criteria necessary for a document to be included.

The Perlin Papers suggests that material collected under surveillance is unreliable. Because we cannot see the people speaking at the dinner party or hear everything they say, we cannot contextualize their words. Once language becomes separate from its immediate context, it’s meaning can be interpreted so as to fit another’s purpose. During the McCarthy era of unilateral indictment, this kind of interpretation inculcated a society of fear. Perlin unmasks this process, revealing the ways “those who work to make things visible and those who work to make themselves invisible.”