This week, we welcome back graduate student, Mev Luna, to conclude our Fall 2016 season with some thoughts on László Moholy-Nagy’s films and experimental music group, Text of Light.

Line. Movement. Composition. Transparency. Layered forms. All of these adjectives can be applied to the large breadth of work by László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), as seen in his recent retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago, Future Present. They are most pointedly expressed in a series of films he made in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In Marseille Vieux Port (1929), we enter the city through a map, a composition of criss-crossing, parallel, and perpendicular lines of various thicknesses. The map is punctured by a pair of scissors and becomes a view hole to footage of the city. The relationship of these collaged elements–that the city is an extension of the lines on the map, and conversely, that the map is a representation of the city– highlight the correlation between image and signifier. In the way that the line lends itself to the representation of streets, there is an inherent geometric nature to the metropolis, which yields these diagrams that have a strong relationship to formal compositions. In this way, Moholy-Nagy primes the viewer in his approach to the film. The metropolis, is a dynamic space when activated through Moholy-Nagy’s film becomes a study of light, composition and form.

In Berlin Still Life (1932), Moholy-Nagy’s sensibility towards the subjects in this film–be they architectural, human, or animal– is equally weighted. The camera follows the sidewalk patterns as much as the feet walking on them. It gazes down at a smiling toddler, and yet later repeats the same composition with a similarly bemused alley cat. Much of the film is shot from above, watching the city over the ledge of a building and skewing the frame. But the camera is also autonomous, moving through alleyways, busy streets, and gazing up in as steep an angle as when it looks down. Moholy-Nagy’s use of jump cuts reminds the viewer that the film is as much about the composition of each shot, as it is about its subjects. A sort of look here. No, not just at that person walking, look at the archway, the stacking of the repeated pattern of light, shadow, light, shadow, from the sun casting it’s way between the buildings that share this tunnel. The film ends with a street vendor selling windup pigeons, an unusual reference to the intersection of life and technology at the time, but nonetheless a strong indication of Moholy-Nagy’s own interest in these subjects.

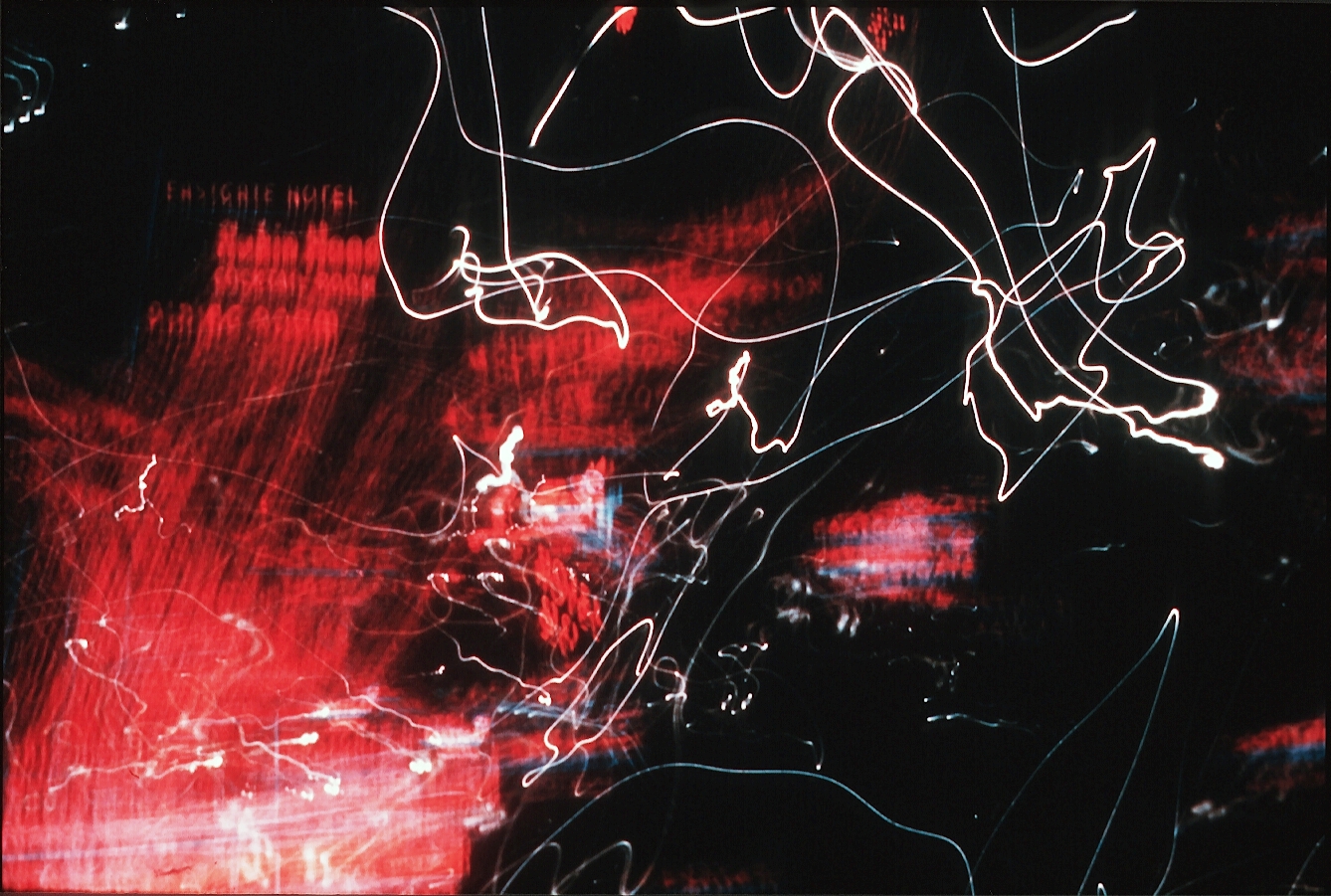

In Light-Play: Black-White-Gray (1930), made by filming the reflections and refractions of light through his kinetic sculpture, Light Prop for an Electric Stage, the first image features the words “Moholy-Nagy zeit” printed on a translucent spinning sphere. In this initial instance, the filmmaker places himself as part of the machine, an appropriate place for this innovator and artist that regarded design as “the integration of technological, social, and economical requirements, biological necessities, and the psychological effects of materials, shape, color, volume and space.” As if revealing cinema’s relationship to these properties, the next frame is light pouring through a roll of film and casting layered shadows as the artist manipulates its form, bending and wrapping it around itself. From there we are quickly whirled into a kinetic composition of shadows, geometric shapes, and lines that seem to collapse in and out of flatness. These forms reconstitute themselves through the employment of double exposure and motion, embodying the interdisciplinarity of Moholy-Nagy’s artistic and design practice.

Seven years after making this film, and and four years after Bauhaus was closed, László Moholy-Nagy relocated to Chicago, where he became the first director of New Bauhaus. The New Bauhaus (eventually renamed the Institute of Design) was founded to bring the principles of the Bauhaus to North America. There, Moholy-Nagy rethought the Bauhaus’s original curriculum, adding photography, filmmaking, music, and poetry. It’s only appropriate that for this special screening, the experimental music group Text of Light will accompany these films. Founded by Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth and Alan Licht in 2001, the group will be joined by percussionist Tim Barnes of Silver Jews. Together, these musicians layer sound, creating an improvisational soundscape for Moholy-Nagy’s radical imagery.