We close this season of Conversations at the Edge with a performance and video by New York-based interdisciplinary artist Sondra Perry whose work critically examines the technologies and power relations that affect representation and black identity.

This week, we welcome School of the Art Institute of Chicago graduate student Lindsay A. Hutchens to reflect upon Sondra Perry’s Lineage for a Multiple-Monitor Workstation.

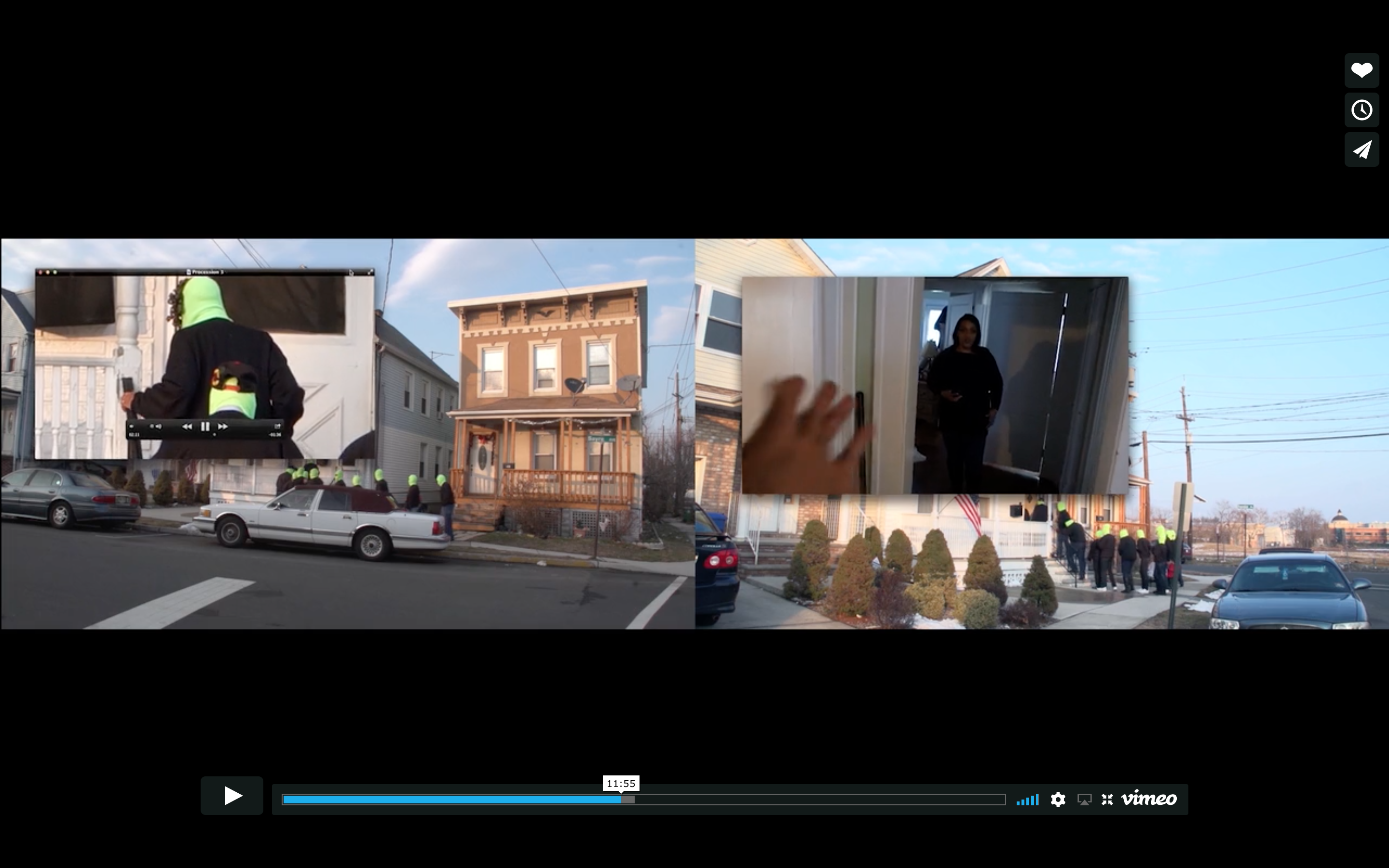

Sondra Perry’s Lineage for a Multiple-Monitor Workstation: Number One (2015) begins in the midst of a time-honored tradition: staging a family photograph. The viewer is positioned so that we are across the street looking back at a family in matching black sweats and chroma key green ski masks arranged in front of a home. They look cozy and warm on what would otherwise be a miserable cold and grey day. “You don’t have to do it if you don’t want to,” is shouted from the camera, from Perry. Directions to aunts and uncles are given and repeated. “CCCHHHHHHEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEESSSSSSSSEEEE. CCCHHHHHHEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEESSSSSSSSEEEE.

CCCHHHHHHEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEESSSSSSSSEEEE.”

Perry frames this video against a chroma key computer desktop, which she uses to choreograph multiple windows and files of her family and more. While her works have been installed at MoMA PS1 and screened in theater spaces, I have only ever seen Sondra Perry’s Lineage for a Multiple-Monitor Workstation: Number One, or any of her videos on her website. There, I’ve viewed them by myself, and in a way that mirrors many of the visual systems she references.

Sondra Perry’s work first came into my consciousness thanks to my good friend and curator, Natalie Zelt, who lives in Austin, Texas, but is from Houston where Perry has been a CORE Artist in Residence at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston. I regularly make photographic and video work using my own family as subject matter, and Natalie knows this. Coming from what seems to be a much larger family than myself, Perry has fascinated me by drawing attention to the role of photographic mediation in intimate relationships. The camera is the loudest of all participants in the video, highlighted in layered windows, visible access to play buttons and runtimes, audible direction from behind the camera, and its presence repeatedly in the hands of those being recorded. Country also plays a role. Rituals involving the American flag are played out, first subtly and then explicitly. But it is the moments of specificity to Perry’s family that bring us closer, provide access, and establish the stakes. Perry’s grandmother is trying to tell about her process of burying flags too worn to fly, while her mother loudly proclaims “It’s under the collard greens!”

In one early scene, Perry shows her hand as a director. Handing the camera off to a relative, she asks her mother to respond in a certain way to the sweater she is wearing. For a moment, the audience is just as confused as Perry’s mother. She knows the sweater, but is she meant to know the sweater? She’s acting surprised, but is she meant to have expected it? Direction is given from on-camera Perry as well as the male voiced videographer, both telling the mother in so many words, “you do you.” Mom, perform mom. Not mom, but you as a mom. That’s not how you use your hands. Perform yourself, with direction. Act natural. To which Perry’s mother obliges, and ends the scene by reminding, “Well, you are my baby. You can’t take that away from me.”

Perry introduces heavy bass with Venus X’s 2015 track “Beautiful. Gorgeous. Golden. Girl,” leaping generations with music as well as casting. Three young women cheese in selfie mode and dance on the sidewalk, two with long glossy ponytails popping out the top of their chroma key green ski masks. They record themselves in a way no one else has yet. Flipping hair. Giggling. Performing without being directed on-camera. Their youth brings attention to the hyper-visibility of the chroma key green ski masks, and pushes against Perry’s control as maker. These women have literally cut a hole in the masks for their hair to poke through, which Perry combs with care in return.

The final scene shows Perry’s entire family together at the table, poised to peel sweet potatoes or yams, again in matching black sweats and ski masks. Another family tradition, warm and cozy, which makes me almost smell Thanksgiving. Perry asks if her grandmother has chosen a song for everyone to sing while they peel, and eventually accompanied by hand claps, together they sing a gospel about family caring for one another. Another direction is given from Perry to “try and connect with each other, somehow, without talking.” Nearly to the end, Perry’s grandmother is seen at the table, having finished with peeling, attempting to remove her mask. She has a ponytail of her own, greyed and in curly tendrils but just as playful as the three young women, and Perry’s mother along with a masked female relation reach over to help so as not to mess the matriarch’s hair.

Perry’s Lineage for a Multiple-Monitor Workstation: Number One embraces conversations about agency and representation in lens-based work, as well as the ways traditions and ritual are passed down through family But it’s through these in-between acts of care and affection–ponytails being guided in and out of ski masks–which Perry seems to have picked up on in the moment, in the middle of construction and long after suggestion of non-verbal intimacy, that do something more for me. They remind me of sitting in front of my grandmother’s chaise lounge so she could brush my hair while we watched The Golden Girls together. That is the thing that pricks me—these moments in which media is entwined with care.