This week, we present The Nation’s Finest, a program that deconstructs the athlete body – how it is used for national, political, and social agendas, and how it is viewed and re-crafted by artists (who are sometimes athletic!). Curated by Astria Suparak and Brett Kashmere, The Nation’s Finest is part of A Non-Zero-Sum Game: Sports, Art, and the Moving Images, a series of exhibitions and events launching, and part of INCITE: Journal of Experimental Media’s newest issue, Sports.

For this post, we welcome School of the Art Institute of Chicago alum, Jacqueline Surdell (MFA 2017) to reflect on the work in this screening, relating back to her own interdisciplinary artistic practice and past experience as a former athlete.

The Nation’s Finest

Jacqueline Surdell

Writing now from the perspective of a practicing artist and washed up athlete, I work, struggle, and play with sport on personal and philosophical levels. I see the general sphere of “sports” as a genre of labor relating to contemporary society. The latter is considered through representations of the commercialized and increasingly brutal field of sport.

The Nation’s Finest features work by artists Haig Aivazian, I AM A BOYS CHOIR, Tara Mateik, Nam June Paik, Keith Piper, Lillian Schwartz, and the Internet. The work included in this program is an apt conduit in which to study, probe, and consider the overlapping spaces sport occupies within popular culture. Employing sport as a framework, the artists present sport-like/sport-ish performances and videos to ask questions about gender roles, nationalism, anger, and resulting violence in contemporary society. Overall, these artists demonstrate that the actions of sport — gesticulations both in, around, and through the actual game — are inherently political.

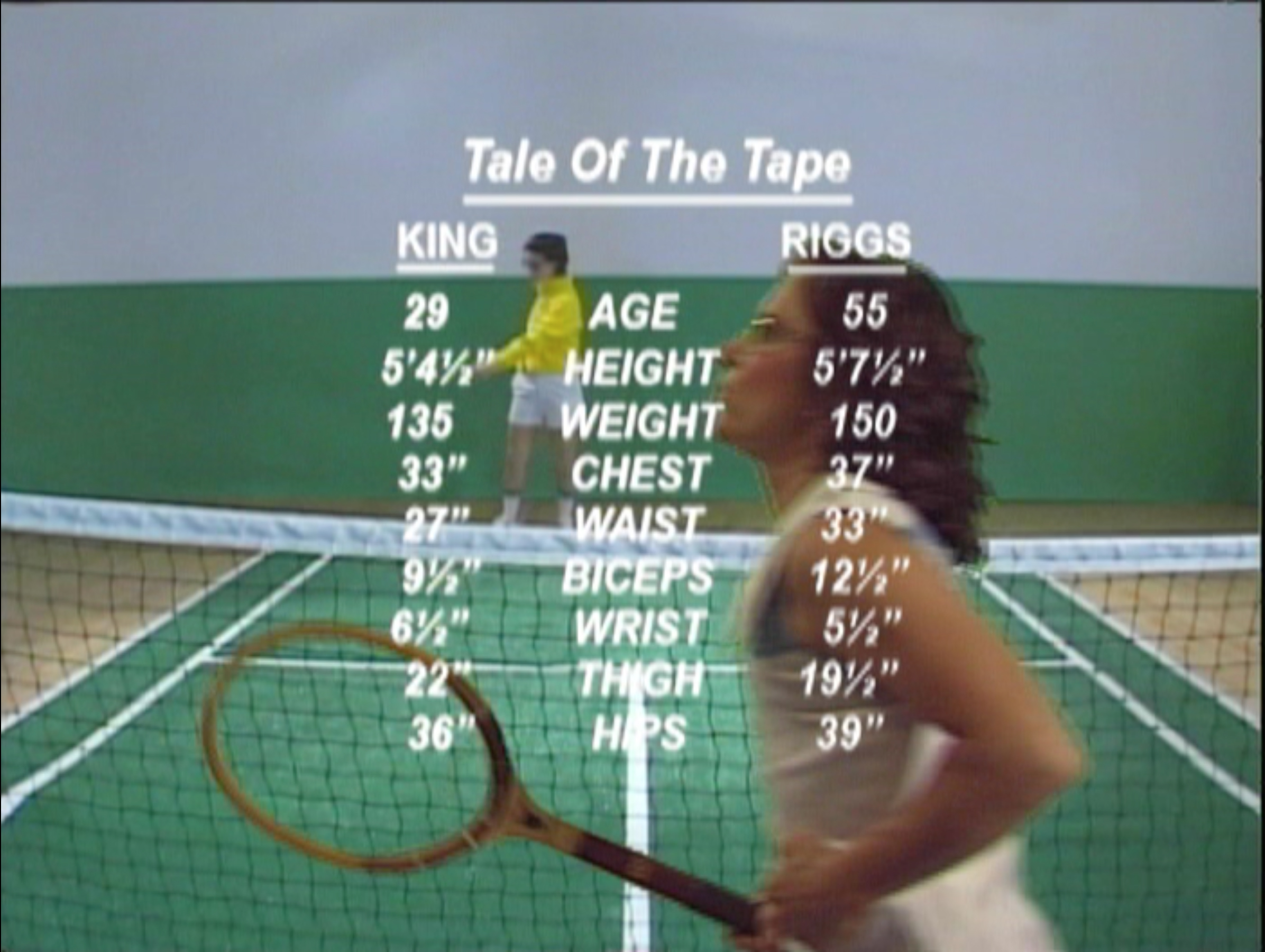

Tara Mateik considers the changing roles of women in contemporary society through a playfully tactful rendition of the historic 1973 tennis match, Battle of the Sexes. Beginning with collaged images and interviews of actual news coverage, Mateik’s consideration devolves into a performance where the artist himself plays both Billy Jean King and Bobby Rigs in the infamous match. What begins as an almost cliche montage of sexism and pushback of the women’s movement during the 1970s evolves into a smart and savvy consideration of the ways remnants of this latent sexism reverberate in the now. Mateik accomplishes this through a well-crafted video installation that includes a large screen, a green plane, white lines, a blue cooler, sideline chair, and complete with ball handlers. Mateik incorporates the illusionism of theater set culture in order to play out an epic saga of gender play. The result is a visual reminder of the ways in which gender is coded, performed, and stereotyped as unnatural occurrences that are socially constructed courts of difference.

Humor is a key player in what makes Mateik’s gender theater accessible, relatable, and deeply resonant. Similarly, demonstrating the imaginary body by I AM A BOYS CHOIR employs a glitterful-twisted humor and role-play forcing the spectator to think through gender performances, sexuality, and openly confront the disavowal of queerness present in contemporary sport. Collaged scenes of men squeezing into blue sparkly uniforms, standing on cement platforms and performing figure skating poses for the camera are paired with a spit-fire verbal rendition of the ways we are coded to understand how someone is “supposed to look”. The work further serves to challenge stereotypes associated with the masculinity of sport and constructed effeminate nature of art. Something curious of note is the effort to think about the performances of gender and sexuality through what is largely considered a “feminine sport”.

The endlessly elaborate costuming of glittery, strappy, and short dresses over skin toned tights combined with the actions, the stereotypical thinness of figure skaters, even the demonstrations of extreme athleticism never confront watchers with a question of her sexuality. Yet the sexuality of male figure skaters is always questioned. Spectators can be objectively safe in assuming the women they are watching are attractive not only in their athleticism and idealized bodies but also in their perceived straightness and purity. demonstrating the imaginary body challenges viewers to consider the reasons perhaps women figure skating is relatively visible whilst other female sports (i.e. rugby, lacrosse, etc.) are left out of the broader conversation. Demonstrations of queerness or possible queerness are quenched and silenced in their invisibility. In response, I AM A BOYS CHOIR highlights and glorifies queerness in lieu of straightness.

Both Keith Piper’s The Nation’s Finest and How Great You Are O Son of the Desert!, Part I by Haig Aivazian consider the devastating realities of race relations deeply intertwined with nationality, classism, and violence as played out and mirrored in sport. In The Nation’s Finest, the viewer is confronted with images of blackness contrasted with gyrating images of the English flag — presenting black athletes as equatable with the symbol of national pride. Incorporating a very literal juxtaposition of glowing black bodies performing on top of the red, white, and blue coloring, Piper calls upon the histories of countries such like Nazi Germany and the GDR that historically used their athletes as tools — a means to an end — in attempts to construct a sense of international respect and internal nationalism. The work forces viewers to contend with the ways in which the labors of the successful athlete of color functions as both liberation and entrapment. By employing historical images reminiscent of modernist propaganda, Piper strategically and subtly leads to the sense of violence happening beneath the surface of sport — referencing the lack of agency of individuals in a broader system of constructed powers.

Aivazian, on the other hand, uses a historically violent sport scene — “the headbutt heard around the world” — to reveal a dark underbelly of anger, conflict, and the ugliness of human nature. Aivazian sets the scene: a soccer match between France and Italy, two countries with historically competitive histories. Within the first minute of the video we are presented with an extraordinarily violent act of Zidane headbutting Materazzi in the chest, causing Materazzi to crumble to the ground, writhing in pain. In post-game analysis, lip readers determined Materazzi verbally assaulted Zidane calling him, “the son of a terrorist whore” before being headbutted square in the chest. Aivazian uses this instance as a narrative through which to consider the complicated internal and external conflicts of race, class, and nationalism within France and beyond. This instance of “combustion” on the field represents a general feeling of disquiet. Like Mateik, Aivazian uses the symbolism and signs — the language — of drawing up sport plays in order to reveal internal violence, racism, and police brutality within France. A sense of “unfair play” is highlighted here as a representation of the uneven playing field that is life for individuals of color, immigrants, and youth.

My understanding of discipline, hard work, dedication to craft, and social sensitivity comes from my years as an athlete. I was not someone who identified with the entirety of “sport”, which typically evokes an image of the football playing male dominant. I was a volleyball player. This specificity is important as I consider, in hindsight, my “sport experience” as a powerfully feminist, and queer, fantasy-like space of shared growth. My teammates and fellow volleyball players remain some of the most badass, beautiful, strong, fierce women I know. Our coaches, head of the club, and trainers were predominately gay men or female. In this way, my understanding of sport subverts broader connotations of sport as conventionally masculine.

Within our utopian-volleyball space, social issues were always present. When participating in tournaments in some of the white-washed suburbs, other teams would ask our team (predominantly women of color) if we were “from Chicago” and if so were we from “the inner city”. Such instances marked my first blatant experiences with the ignorance that belies bigotry, racism, and classism. We had no set rhetoric (or time for that matter) to discuss critically the ways in which these experiences impacted us. In fact, it is without a doubt that my whiteness functioned(s) to shield me from other present transgressions. Instead, we used the experiences to fuel and uplift our level of play — moving on with our bodies and shared knowledge of being collectively, and unwarrantedly, underestimated.

On a broad scope, sports represent an acute, stripped down, rendered, and commercialized version of contemporary society. There are endless examples of sport touching on issues of gender, race, national identity, and beyond. The Nation’s Finest is a positive representation of the interrogation of sport and art, further increasing scholarship on the evolving relationship between these cultural siblings.