We end our spring 2018 season with program featuring the work of prolific interdisciplinary artist Joan Jonas.

Jonas is a pioneer of performance and video art whose career spans more than five decades. As one of the most important female artists to emerge in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Jonas has pushed the boundaries of these two disciplines through large scale installations and collaborative projects. Her work is currently the subject of a massive retrospective exhibition at the Tate Modern.

This week, we feature an excerpt from an article written by Jonas for the Guardian in which she discusses the numerous and various influences that have helped shape her work.

Mirror mirror

Joan Jonas

I am always reading something: newspapers, periodicals, poetry, philosophy, fiction and non-fiction. I’m interested in many forms of narrative, of storytelling – movies and television, dance and theatre. Naturally not everything I read or see ends up becoming a part of my work, but sometimes a story sticks in my mind – I can’t get rid of it, and then I begin to analyse what it’s about, how it works and why it has taken such a hold on me.

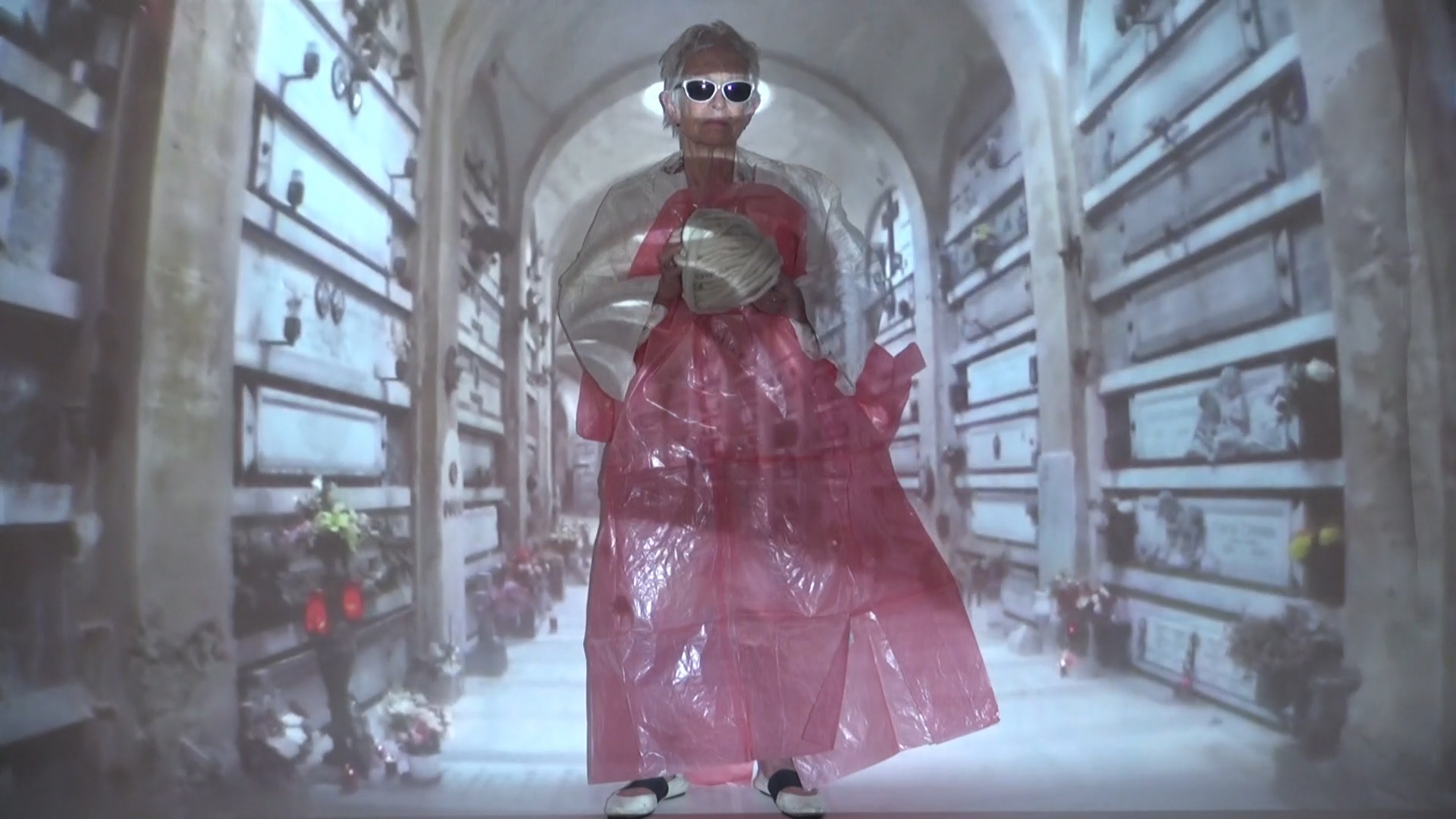

In the early 1960s, when the writings of Jorge Luis Borges were first published in English, reading his work was a transformative experience. For one of my earliest solo performance works in 1968, I made a costume that had mirrors of various sizes attached to the material. For the text, I took every reference to mirrors from Borges’s Labyrinths and assembled the excerpts into a script, which I memorised and recited aloud.

Mirrors and poetry, as well as myth and fairytales, refract reality in unexpected ways. Mirrors can collapse or confuse the distance between performer and audience and disrupt visual frameworks. When I use a myth or a story or a literary text in my work, I often extract particular passages from a larger narrative that resonates with me. In performance, the audience hears the text, recorded in advance or recited in real time, in fragments, and sees components – such as movements, props, drawings and video – that may relate only indirectly to the text. I don’t change the language, but rather I change the context, which opens up the text to different possibilities of meaning. I don’t illustrate; I juxtapose.

Read the full article here.