During his visit to SAIC in this week, Peter Burr sat down with CATE Curatorial Assistant Nicky Ni for an interview about his background in painting and drawing, his iconic computer animation style, and his multimedia practice that spans from video, performance, to immersive and interactive game installation.

NN: Could you give a brief summary of where you’re coming from and how you got to where you are today? I notice that your earlier body of work is different from the program you screened at CATE last night.

PB: I went to Carnegie Mellon University for undergrad, a school that had so much expensive technology and radical professional discourse. I grew up using computers, but nothing to the magnitude of the access that I had at CMU. Initially I studied panting and enjoyed putting a lot of labor into each individual image. I gravitated toward time-based work in part because of the labor that was involved. After I discovered After Effects as a tool to collage things that I found on the Internet I got excited about using the media I grew up on—the games, movies and television—and reverse this firehose of mass media by switching from full-time user to full-time maker…There was something cathartic about it.

After CMU I started the video label Cartune Xprez, which was born out of my connection to the Bookmobile Project: An Airstream trailer that took yearly curated zines and publications on tour. I joined this project in the early 2000s and ran it together with a group of artists and activists from North America. One of the core goals of that project was to take art forms and ideas that are confined to a small output (in this case we exhibited zines and artist books) and distribute them to a larger community. My former interests in animation, performance, installation, and my exposure to the Bookmobile Project, made me realize that instead of making work for film festivals, I could create my own mechanism and take the work on tour. So, I started Cartune Xprez, sort of a touring roadshow, and my work became intertwined with a community of artists who worked at an individual capacity with a sensibility of bridging high-brow and low-brow cultures.

That changed a lot several years ago. I was turning 30, and there were just a lot of factors in my community and in my values that were changing. I realized that my practice as I had built it thus far wasn’t serving the person I was becoming, so I took a break. When I reemerged, my practice looked more like the work we saw at CATE.

NN: You once said that you wanted your work to be scalable — from festival screening, performance, to Time Square take-over — how is this versatility important to you both conceptually and strategically?

PB: For me that doesn’t seem to be a very conceptual maneuver. I get motivated to make new work by thinking of some radical formal gestures that I have never made before. Like Dirtscraper, I was motivated to make a room-size multi-projection interactive computer simulation. I was able to devote an entire year making a work that thus far has only been seen in one room in Richmond, Virginia, in part because of the knowledge that I could fluidly translate it into other forms. In terms of access, I want people to see this work, so I think of it in an open-ended capacity. As the CATE program revealed, all of this installation and performance work has the potential to become a work of cinema to continue its life long after the genesis form has disappeared. I guess you could also trace my interest in this approach back to the moment when I graduated from university. At the time I no longer had access to a computer after primarily making computer-made time-based work for the previous few years, so I just started to make zines and comics. I think this idea of scalability and self-sustainability has always been at the core of how I operate.

NN: I was re-reading Hito Steyerl’s “In Defense of the Poor Image” and was thinking about this question of accessibility. She argues for wider accessibility at the expense of sacrificing some quality, and it seems to me that your being very fluid about translating your work into various forms is aligned with that.

PB: I love that. One of the things that plagues me is that I don’t always have access to spaces that have a high standard of quality to show the work. I make work to each individual pixel, and the way I have been dealing with this over the past few years is to simplify the resolution of the materials. Now I have a 4k monitor and I spend a lot of time working with all these images, feeling really bound to the integrity of each individual pixel. So, when shown at places without certain standards of output, the work just won’t be as powerful—I know that and I’m fine with it. It still has these visceral and blunt gestures, but there are details that are lost–the micro nuances that create certain key effects.

NN: Indeed, you have a very iconic animation style that visualizes every pixel and generates dazzling moirés, which seems to underscore the digital nature of the work. Can you talk a little bit about this aesthetic choice and how it conceptually folds into the narrative?

PB: As I said, I was using digital tools as a way to collage different sets of imagery, but when this strategy no longer served me at an emotional level I stopped making work. When I came back to my practice after a healthy break I had begun Freudian psychoanalysis and was encouraged to dig into older aspects of my own life. I thought a lot about the first tool I used to make digital graphics: a software called MacPaint on a black-and-white Macintosh computer. So, I started to make drawings using a MacPaint emulator and I got really excited playing with different fill patterns. There I saw a formal continuity between the maximalist collage work I used to make and the much more sober work coming out of this MacPaint doodling. Over time I taught myself to translate these tools into more contemporary technologies. The works we included in the CATE program underscores the continuum of this translation.

There are also practical reasons this work looks the way it does. This aesthetic sensibility you’ve pinpointed is also a workflow in which broad strokes can contain a lot of detail. I can make longer films from larger gestures that otherwise would take a huge team to accomplish. Like if I were to make the next Red Dead Redemption game, I would need to hire 400 people and it would still take over five years, haha.

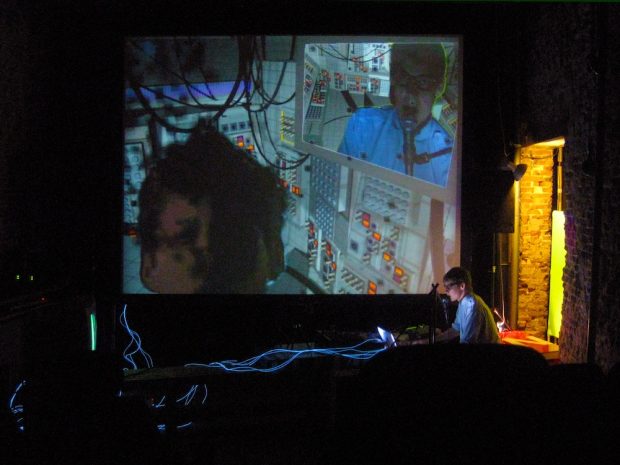

NN: One of the films you screened at CATE, Special Effect, originally was a performance. Do you still perform it?

PB: I think after I had traveled for some 50 shows over the course of a couple of years, the act of performing started to lose its shine. As a result, I was thinking more about how to archive its liveness within a digital spectrum. And that’s how I got thinking about video games and how to translate this project into something where I replace myself as the actionable center with someone from the audience.

NN: You have done some VR projects and have expressed interest in turning existing work into more immersive installation. What do you think full immersion can provide to the participants in relation to your work? From what I observe there are so much skepticism and hype around this type of technology.

PB: Sure, I would say that there is a lot of hype around all kinds of new technology. Comparing forms of media, AR, VR, cinema, painting, and games, I think books are still the best interactive medium. When I’m reading a good book and I’m immersed in it, it creates this fusion of my own experience and the world that I’m living in. Perhaps what I find exciting about VR—or WR for “whatever reality”—is that the rules around it haven’t been so codified yet. Cinema, for example, has been around for more than a century and many core conventions of how to tell a cinematic story have already been discussed. For these newer technologies, the grand scheme of things hasn’t been set yet and it feels very exciting to be making these discoveries.

NN: Thank you Peter!

Nicky Ni is a graduate student in art history and arts administration at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.