On the occasion of her program with CATE, curator Andréa Picard spoke with Kyle Riley about the Toronto International Film Festival’s experimental film and video program, Wavelengths. Picard illustrates the program’s history and evolution, the challenges of curating shorts programs, her curatorial vision, and her first encounters with film. Coming from an art history background, Picard highlights the many intersections between the visual arts and moving image worlds and discusses the changing festival landscape.

Kyle Riley is a MA candidate at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the dual degree program in Modern Art History, Theory and Criticism & Arts Administration and Policy.

Kyle: I wanted to talk first about Wavelengths. I am interested to hear you describe it in terms of what it means to you, what your motivations are and how you see it playing a role within the film community in general and in the festival world in particular.

We’re now heading into our 13th year, so Wavelengths has accrued its own history within TIFF, and has grown a tremendous amount. When Wavelengths was launched, it did so with four programs of shorts on opening weekend, as a forum to celebrate experimental film within a large festival, not unlike Views from the Avant-Garde at the New York Film Festival. Susan Oxtoby, who was the former Director of Cinematheque Ontario at the time, was the section’s founding-curator. The city of Toronto has a very rich experimental film community and history, and the organization’s commitment to non-commercial film and video has always been significant. In that way, Wavelengths was a natural progression, especially given Susan’s curatorial tastes and expertise. The Toronto International Film Festival is a big, very well attended public festival. It doesn’t have a market; its efforts are largely directed toward connecting an engaged and enthusiastic public, as well as attending industry from around the world with the films in its selection. The atmosphere can be electric, charged with the promise of discovery.

The section was named after Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), not only for the film itself but for Snow’s enormous achievements and contributions as one of the world’s greatest interdisciplinary artists. Despite his international engagements, Michael has remained very active in the Toronto scene. While he no longer plays free jazz on a regular basis, he still comes to the Cinematheque on occasion, attends the festival, and has recently been the focus of several exhibitions. It’s been a lovely, longstanding dialogue, and he continues to inspire not only the ethos of the program, but also many of the artists who come to present their work.

While Wavelengths began fairly small and modestly as a showcase for new work, it did so presciently with an eye towards the history of cinema. If I recall correctly, the first year included a gorgeous hand-tinted film by Segundo de Chomón. When Susan left to become the Senior Curator at Pacific Film Archive, I stepped into the role and grew the program. I wanted to ensure a space for visionary feature-length filmmaking as well. At the time (2005) filmmakers like James Benning, Harun Farocki and Heinz Emigholz had not played the Festival in a long while and I felt it was important to re-introduce them to the fold, especially given their recent contributions.

Though still modest within the scope of TIFF, Wavelengths has considerably expanded and now provides a curated space for short, medium and feature-length films and videos that defy easy categorization, such as cinematic essays and hybrid documentaries. Last year marked a major turning point in the program’s evolution, when we collapsed the former “Visions” program under Wavelengths’ umbrella. This new section dismantles the traditional boundaries between experimental film and narrative filmmaking, though we ensure that the feature-length works are definitely made by artists. We champion autonomy, risk-taking—aesthetic and political—unusual collaborations, a sense of urgency and experimentation in a broad use of the term. The former Visions section was my favorite in fact, as it showcased young auteurs making uncompromising works of cinema—ones which are likely to withstand the test of time. There you’d find films by some of today’s most important filmmakers, such as Argentina’s Lucrecia Martel and Lisandro Alsonso, Tsai Ming-liang from Taiwan, Bruno Dumont from France, and one of your most famous alumni, Apichatpong Weerasethakul. As a section that encouraged the pushing of boundaries both formal and of storytelling, its merger with Wavelengths comes at a time when increasingly diverse programs are teaching us that the term ‘experimental’ varies greatly from nation to nation, and story needn’t be incommensurate with formalism.

The shorts programs remain the core and still screen during opening weekend, while the features are spread throughout the entirety of the festival. I was a little apprehensive going in last year, but the changes were enthusiastically embraced. We saw much crossover with the audience and press, confirming my belief that true cinephiles are those with a near-inexhaustible curiosity and a thirst for great cinema, be it that of Nathaniel Dorsky or Tsai Ming-liang, Athina Rachel Tsangari or Aldo Tambellini, Luther Price or Wang Bing—each of whom is avant-garde in their own way. Wavelengths advocates for film and video as art across genres, and beyond categories. We certainly share affinities and a view of cinema with many international colleagues, but I think the merger of “Visions” and “Wavelengths” makes this section unique within the festival world. At least, we aspire to be!

So Wavelengths began as a way to create bridges between underrepresented film and video work and more well-known avant-garde pieces.

It was begun as a sidebar for experimental film, a section to celebrate great artists like Ken Jacobs and Peter Tscherkassky and to discover a new generation of film and video artists. Over the years, the section has grown to reflect the changes in the field, such as the inclusion of visual artists working with moving images. Recently, we’ve presented such celebrated artists as Thomas Demand, Tacita Dean, Mark Lewis, and Francesca Woodman. This facet has become an important progression, as it mirrors the changes in moving image culture while still insisting upon art on screen, and not just in the galleries in installation form. It has, perhaps not surprisingly, also changed my job immensely because I’m now not only working with distributors like the Video Data Bank, Vtape and the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Center, but also important galleries like Marian Goodman, Mathew Marks, David Kordansky, Eigen & Art, etc. Let’s say in some cases, there’s way more paperwork! One of the most exciting things about Wavelengths is the inclusion of little or unknown artists alongside legendary ones and how it surreptitiously shuttles between disciplines while exploring the art of cinema.

That’s one thing that really interested me about your screening last night. You really seem to demonstrate an interest in moving image work that operates parallel to or even directly integrates object-based work. For example, during your Q&A when describing the importance of Michael Snow you made it very clear point to address his object-based practice, and you included works like Chris Kennedy’s 349 (for Sol LeWitt) which makes a direct reference to a visual artist, and T. Marie’s Slave Ship, whose method of manipulating each pixel individually to slowly change the scene seems to be an extremely object-based way of working.

T. Marie calls them ‘moving pixel paintings’…

Yeah, exactly.

As distinct as the history and evolution of cinema have been from those of the art world, its history and discourse, the trajectories have not been entirely separate all along. They’ve run parallel. I think there is a little bit of cultural amnesia that comes with the fervent discussions about moving images suddenly being embraced by the art world. One can look to the history of several avant-gardes, from Russian Constructivism, to Surrealism or Dada, through Fluxus to see a dialogue between disciplines, including painting, photography, film, poetry and performance. Of course, it’s much more complex than that but in thinking of film as an art form, rather than popular entertainment, that dialogue has a long history, relatively speaking. That’s not to say that cinema has been completely understood or properly embraced by the art world, especially when we see just how poorly installed many moving image works are within galleries or museums. But we’re certainly at a point in time where moving images are so prevalent within the museum space that in the art world there is renewed interest in the cinema and its own history, narrative and otherwise. Artists like Francesco Vezzoli for instance, or even, it’s too obvious now perhaps, but Christian Marclay, Jesper Just or Douglas Gordon, are mining the history of cinema. Cinema as spectacle, cinema as popular entertainment and iconography, while the form largely becomes subsumed by their own formal preoccupations; in some instances, their lack thereof…and suddenly, the ethics of appropriation is one hot topic!

I think we’ve finally reached a time when the art crowd will commit to attending film programs with a set start time, as opposed to wading in and out of a black box. Wavelengths attempts to harness this interest by including a few big named artists to lure them in, to act as hooks, as say Francesca Woodman did last year. Once there, many appreciate the dialogue between experimental film and video with other disciplines like painting or sculpture or are simply impressed or inspired by what they see, and hopefully want to see more. This renewed interest in the cinema has also resulted in flourishing film departments in museums throughout the world. The best ones don’t just showcase film and video as supplements to their exhibitions but celebrate the art of film for its own achievements and merits and draw an enthusiastic crossover audience. Tate Modern and Le Centre Pompidou do this very well. I’m speaking generally here, of course, but I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that much of the art world needs to learn how to think, write and theorize about cinema. I don’t mean a formal education per se but Cinematheques should be benefiting from this desire to see cinema presented in true museum-quality conditions, and in increasingly rare archival prints. The internet can provide plenty of context (true and false!) but the real experience is still to be found on the big screen. Real and romantic.

An exciting intervention, at least I found the gesture to be wonderfully polemical and incisive was Austrian Filmmuseum Director and curator Alexander Horwarth’s impressive film program for documenta12, which acted as celebration, as much as a speculative corrective. Presenting key works of cinema across all genres, from Classical Hollywood, Modernist European masterpieces to experimental film, the list could be interpreted as the non-existent archive or history of films that could have or should have been included in what is arguably the world’s most important art event. The films were shown in the cinema every day for the entirety of that documenta, the history of their non-inclusion rendered cheekily implicit. His inspired programming put Hitchcock, Chris Marker and Robert Smithson on the same program, linking notions of memory and utopia. His program (at least on paper, I was not there), while avoiding the trappings of pure chronology provided a fascinating excursive through film history, one which is too often shrouded in myth or hews to a staid historiography. The series also made it very clear that cinema is an art form reliant upon the conditions of its exhibition, i.e. that something special happens when films are properly projected in a cinema and collectively viewed. Similar issues are what compelled me to found the Film/Art column for Cinema Scope magazine. In some ways, it was a reaction against so many of the poorly installed moving image installations in galleries and museums that did a great disservice to the artworks by not honoring or understanding their fundamental properties and exhibition needs. The damage done to poorly installed film works is so much greater than that of a poorly hung painting.

That really speaks to what I thought was an interesting contrast between Chris Kennedy’s 349 (for Sol LeWitt) and Henri Storck’s Pour vos beaux yeux. The intentionality of that contrast seemed so apparent.

It was a bit crazy!

Yeah! That was so interesting to me, but it makes perfect sense in light of what you’re saying about trying to collapse that perceived distinction between art and cinema in an attempt to show that it is a very similar dynamic that has existed throughout the twentieth century.

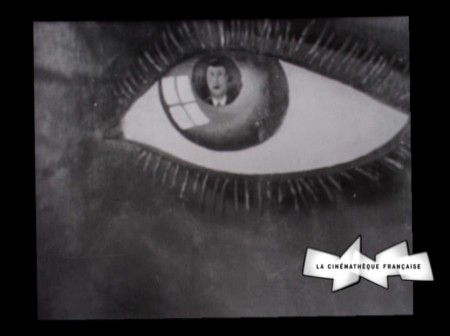

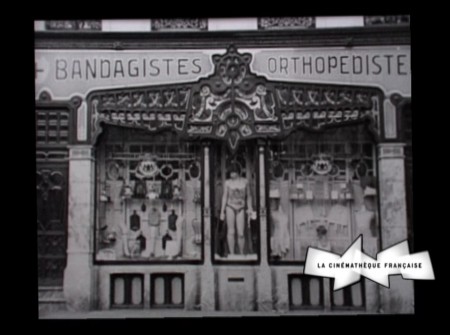

Absolutely. Just thinking about that artwork by Sol LeWitt: it’s a wall painting, and what is a wall, if not traditionally very flat. So is video. It’s flat, or as filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin colorfully puts it, it’s a big block of Formica! Its compression affects your perception because of its pronounced lack of depth (also with the color-melding as can be seen in Chris Kennedy’s hyper-edited video). There’s an internal binary occurring, however. Then to segue immediately to the Storck, which is also relatively flat in that it was largely shot on a stage, is very theatrical and awkwardly and charmingly artisanal. But it was shot and projected on 35mm and thus we feel the depth of field with its swirling grain, despite the acute foreshortening of its mise-en-scène. I knew it would be jarring but I wanted to know how it would affect the senses to go from one to another, with their 70 year gap.

I liked how you described it as ‘disjunctive programming,’ because visually it is such a stark contrast. Is that a strategy or device for you to sort of jolt people out of thinking about film genres?

It’s not a strategy, but I am very much aware of giving works their own breathing space, which is a very difficult to do, especially in a festival context. Creating shorts programs is more difficult than perhaps people perceive it to be. One doesn’t simply want to put works together that deal with the same theme. Whether films are 1 minute or 23 minutes long, I consider them original works of art, and want to ensure that they have the right context and the proper breathing space, which is always a challenge. I don’t want to create a program in which everything melds together and produces an overall impression, as I wouldn’t be doing justice to the individual works. You have to find a way to allow them to exist on their own, while also complementing the other works in the program. I tried to do that in last night’s program, despite it being a sampler, it meant to give the audience an idea of the kinds of films and videos we’ve championed. I wanted to ensure a few threads to awaken the audience’s imagination. Whether it was the painting thematic, or the more political works—and how they’re implicitly political, not overt—the films contributed their own textures and expressions while forming a cumulative one that worked along several lines. Compelling and mysterious ones, I hope. Mystery as strategy? Or perhaps contradiction or paradox, such as the sensual in the austere. Maybe we should be talking principles over strategy!

When you say that the way that you structured the screening last night in a way that you wouldn’t normally do, how would you describe what you would do in a more institutional context? How would you describe your curatorial practice as a film programmer? How do you approach curating Wavelengths, either thematically or structurally?

That is a difficult question to answer categorically because programming for Wavelengths is very different from curating for other institutions or other contexts, where I might attempt to subvert or fill in the canon. Wavelengths is very much a forum for new work, as festivals mostly are, with a few restorations to enrich the dialogue. Four fairly taut short programs (lengthy shows can be a drag and deter from the strength of the individual works) means that the competition is fierce with very limited space relative to the number of submissions. In all cases, I look for films that move, surprise and inspire me, that momentarily quell my existential panic, that remind me of the power of art to change the way we look at and feel about the world, that evince a certain urgency, that restore the power to moving images in a world run rampant by so many meaningless ones. I am a formalist at heart so if something doesn’t appeal to me on a formal or aesthetic level then it’s difficult for me to engage with it. I try to make the program as diverse as possible while never making any token concessions. In that way, the curating process is collaborative as my reach only extends so far. I rely on the generosity of others from around the world to suggest works that eschew or do not have access to traditional distribution channels. I solicit directly from filmmakers, galleries, artists, distributors and other curators. By and large, the programs cohere around a theme, not so much for convenience’s sake (such as marketing concerns for instance) but under a certain curatorial rationale that when successful is also provocative and surprising, like the art it represents. Disjunction can also work wonderfully in this context.

Last year, for instance, I showed Pipe Dreams by Lebanese artist Ali Cherri. The video deals with the rapidly changing situation in Syria and how artists grapple with history as it unfolds. I juxtaposed it with a Lillian Schwartz restoration because Cherri’s video is about the first Arab astronaut, and Schwartz’s is a completely abstract (and newly revealed to be 3D!) film called UFOs. It was a somewhat cheeky move to segue from a political work to a playful, eye-popping one, but I think the effect was greater for both because of that difference. One could argue that they are both dealing with space: the space of history, actual space, cinematic space. Disjunction can sometimes awaken rich readings, rattling our brain out of our customary ways of thinking. I like to play, to be conceptual on some level, but never (at least I hope not) to the detriment of the films I am showing. I often think about curating films and videos in terms of sculpture, whether or not that is a “proper” approach. Conceptual sculpture, then! Texture plays such an important role, even more so now that we are living in a multi-multi-multi media world. I think of texture as an elusive quality that one must attempt to bask in, like time regained. I love the paradoxes that cinematic texture conjures, in all of its illusionism. This again points us back to proper presentation conditions, and the splendor of the big screen for film and video works alike (though different). I wish all curators and film programmers, myself included, had the luxury of pre-screening works in their exhibition copies projected on the big screen. It makes a world of difference—laptop viewing does a poor job of representing an artist’s expression meant for large-scale in-cinema projection.

So you began curating Wavelengths in 2006. Is this sort of process that you are describing, the things that you are interested in and the spaces and conversations you are interested in creating, something that you arrived at as an approach right from the start or has there been a gradual movement towards this in your practice at Wavelengths?

Prior to that I was programming at the Cinematheque, and I continued to do both for six years. In some ways, I am always looking toward the past in order to grapple with the present. I have such a profound love for so many films from the history of cinema that I am motivated to discover new work that will withstand the test of time, to find traces of greatness from artists I’ve never heard of. In all of my work, I’ve attempted to veer from a prescribed canon, have attempted to suggest alternate ways at looking at bodies of work, to fill in gaps and to look in unorthodox places, to follow my convictions, to risk being unpopular in my choices in order to defend work I belief in, to take a chance on work that I don’t fully understand, as well as to say no to certain artists or works which can be the most vexing of all. I think the canon is obviously important, but by its very nature, it exists because of visibility, because someone championed and wrote about those works. It’s overwhelming to think about the films that we will never see or even heard about. The internet of course complicates this by granting access, but way too much. It’s a floodgate that both helps and hinders discovery. Many Farber’s seminal essay on termite art certainly guides in me in endless search.

That’s great. My last question is for you personally. Again, given our discussion about your art history background I was curious how you arrived at your interest in experimental film and video.

Well, it’s because of one work! And it’s not related to film or video at all. It’s an 18th century painting by Jean-Siméon Chardin called The Jar of Apricots from 1758, which belongs to Art Gallery of Ontario. I fell madly in love with this painting, which is, in my opinion the masterpiece of their collection. It’s a still life, but for Chardin a very unusual one as it’s oval-shaped making it both very rare in his body of work, and some argue a lesser painting informed by the fashion of the times. I disagree, of course! While I was studying art history at the University of Toronto we were often sent to the Art Gallery of Ontario to study works in the flesh for our papers so I was there weekly. I would often be writing on Rothko or Agnes Martin or Sol LeWitt, and then I would go visit “my” painting. I would spend obscene amounts of time with it much to the bemusement of the guards, one whom became a great friend over the years. I was a bit obsessive. Then one night the loudspeaker announced that ‘the film is about to start downstairs.’ I wasn’t aware that the Cinematheque was located in the building because I was new to Toronto, so I went down to investigate. The film was Pierrot le Fou by Jean-Luc Godard. I had seen it on television before, but seeing it on the big screen for the first time, I immediately thought ‘this is a moving painting!’ That’s what it is. It’s a perverse work of pop art. Everything is painted in bold, primary colors, and watching it on the big screen in a beautiful 35mm print was a complete revelation, especially with my gaze sharpened from spending so much time looking at paintings. Then I saw Antonioni’s Red Desert, which for me crystallized the relationship between painting and film. My passion continued from there, and obviously led me to the avant-garde, with real paint on celluloid…

That’s an amazing story, and it makes complete sense too in terms of how you approach your curatorial practice.

Yes, that’s when I first saw film as a real art form. With Red Desert especially, I was mesmerized by the painted sets, and how the shots visually rhymed with one another. It was both a startling and beautiful realization. The film became more sexy but also more menacing. I was caught in its grip. I still am…