Everything that grows is inarguably shaped by its environment. The land that hosts and holds us when we’re young becomes part of our very beings. The land where I grew up was haunted. It’s true that the South is haunted in many ways–the region’s history is as ugly as it is bloody. Slavery and civil war, generations of racism under Jim Crow, divides that still exist today. As steeped in horror as the American South is, it’s no wonder that sometimes, these horrors manifest physically.

When I was 6 years old, or maybe 7, I saw a ghost. A young girl, in a nightgown, translucent and glowing, walked across the hallway and into my grandmother’s room. I froze; I was the only one awake, staying up late watching cartoons because my grandmother said I could. It took the better part of an hour before I managed to get up, turn off the lights, and crawl into bed. I didn’t tell anyone. I didn’t sleep.

Before I uprooted and came to Chicago, I focused on documenting my hometown of Greenville, SC. I chose to photograph at dusk and dawn, in-between times for a town in-between phases as it undergoes a population boom. Like William Christenberry and Sally Mann before me, I turned my camera to the land. Christenberry, when asked why he only ever photographed the South, said, “This is and always will be where my heart is. It is what I care about.”

Sally Mann, in turn, says the land has a memory. I never feel that more than during the gloaming, especially in places that still feel untouched by time. The land remembers, the good and the bad. That’s never far from the mind, that the sounds in the woods might not be raccoons. That some lights on the edge of the field are fireflies, but some are too steady and too watchful.

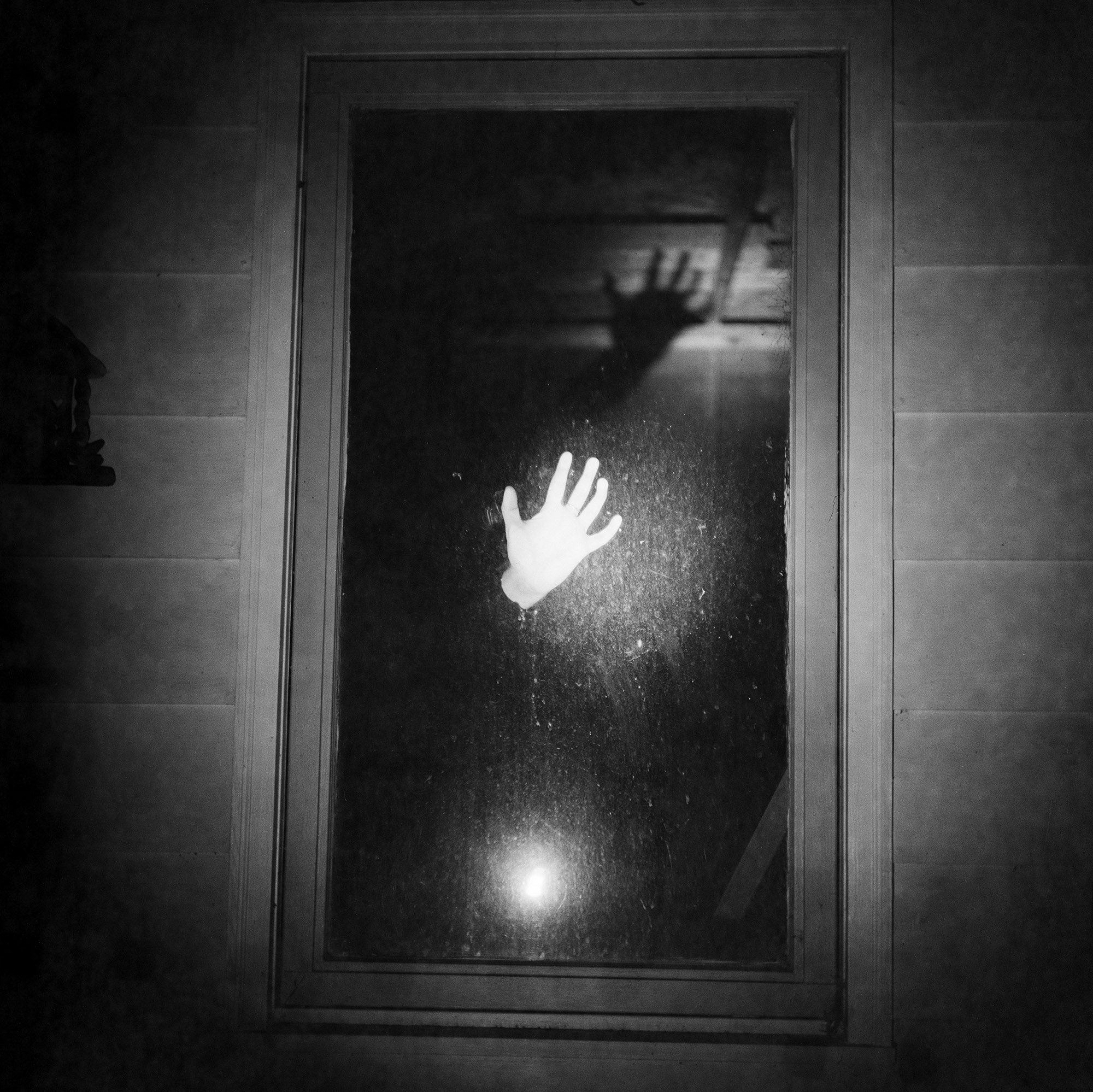

As I explored the city, I came upon a tent standing, alone, in the middle of a park. The urge struck, not just to photograph it, but to put my body in the frame. The tent alone would make Bradbury proud, but the blurred figure of my body gave it the final push into Something Wicked. What did it mean, then, that the wicked thing was me? How often were women depicted as the monster? Is she ghost? Creature? Witch? I began to play with the idea of haunting and the feminine.

Horror is, after all, the only film genre where women are seen on screen more than men, holding 53% of the screen time according to research from the Geena Davis Institute. And yes, while the female lead is often the victim in these movies, she still exists. Moreso, the audience is more often than not forced to identify with her. The ghosts she sees are real. Despite the disbelief of the people in the narrative with her, the audience knows the things she’s seeing exist.

So, what happens if instead of being reactionary, the female lead take charges? Or, to push it further, what happens when women are the source of terror? Instead of just being terrorized? “Who, surprised and horrified by the fantastic tumult of her drives (for she was made to believe that a well-adjusted normal woman has a … divine composure), hasn’t accused herself of being a monster? Who, feeling a funny desire stirring inside her (to sing, to write, to dare to speak, in short, to bring out something new), hasn’t thought she was sick? Well, her shameful sickness is that she resists death, that she makes trouble.” Helene Cixous, The Laugh of the Medusa. To identify as a woman and choose to speak, choose to push against the established boundaries, choose to make noise instead of be still and silent….to choose this is to become something uncontrollable and thus monstrous.

So, I’m turning women into ghosts. But not the silent type, treading footboards after the house has gone to sleep. I give my ghosts teeth.