Bee is an illustrative artist/art therapist. Their practice as an art therapist is one where they incorporate the philosophy of “play,” a space for themselves and whoever they’re with to explore a sense of experimentation and exploration. Their body of work is made of comics and figurative art, both of which are pertinent to the population they strive to work with—the disabled population, of which they also consider themselves a member. Disabled bodies and stories are too often stripped away, taken as mere lines of data and information on a medical chart, and they wish to create spaces where disabled folks can take that control and agency back. Their favorite works as a facilitator have involved an exploration of the senses and experimentation with art materiality, which exemplifies their belief of the importance of play and fun in a space.

My work seeks to explore and allow a voice to the tension that exists between medical trauma as a result of iatrogenic harm—that is, harm caused by the medical system, normally invoked to explain issues of malpractice, but in this case has been altered to refer to the harm of treatment itself. My past exists in a torrent of dehumanizing medical records which at the onset called me “Randolph, Baby Boy” out of sheer necessity, and the continued narrative within those records never grew more in-touch with myself as a human being, or a child. My self exists instead in the form of my own original characters, through the humanity offered through the stories of their time together as friends, and through the physical act of creating soft sculpture artworks of dolls and bowls comprised of yarn and fabric. If my trauma is a ghost, a haunting, a specter which bumps in the night, then my art is the flashlight that illuminates, and the Ouija board which allows me to “speak” to these ghosts with love and a sense of play.

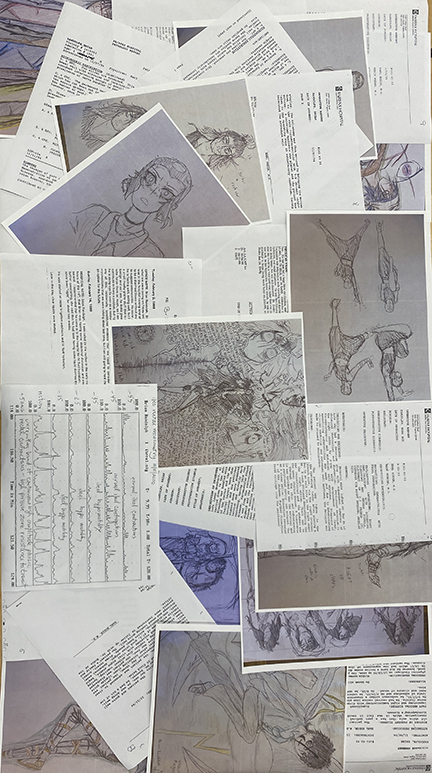

The multi-faceted nature of my work as it pertains to this graduate project means that the exploration of materials and forms of artmaking are vast and, at first glance, disparate. That said, they instead speak to each other through the ways they reflect my experience as a pediatric patient in dozens and dozens of hospital beds. My dolls and bowls are made of yarn wrapped around fabric, a physical action which reflects the wrapping and coiling of the pipe-cleaner animals I made during one of my more major surgeries at seven years old. The dolls, too, reflect the iatrogenic harm, as playing with the dolls (their prescribed function) is an act the dolls have potentially not consented to, and any damage incurred by the act of “play” acts as a parallel to the harm of the prescribed role of “patient.” The comic has elements of the work of comic artist Bryan Lee O’Malley, specifically his debut novel Lost at Sea in the ways that the ghosts of the characters lead them to places of honesty and connection. My comic created here features two of my original characters Elliot and Arryn having a “meet-cute,” and while the flickers of ghosts are present, the focus is instead in the humanizing of the two. The collage speaks to the tension of humanizing artwork and dehumanizing medical records, laying them out plainly for all to see.

As my work continues to evolve, the primary element I wish to focus on is the nature of play, and of the joy that comes from making art about the things I wish to see and experience. A primary struggle throughout the process of this graduate project has been the internal confusion of whether a cute comic about cute characters “counted” as being part of this collection. Ultimately, I landed on the idea that, in fact, this was the most important element. Just as I feel more human and embodied, so too must my characters. Healing from iatrogenic trauma (and, perhaps, trauma in general) is through each other, and perhaps denying Elliot and Arryn their meet-cute would be ignoring the ghost. Perhaps this is what the ghost of trauma speaks through the Ouija board of art: “See me.”

"What's a Doll's Function?" and "Holding Bowls." Dolls wrapped in a manner to reflect pipe-cleaner animals made after the loss of my large intestine, in bowls to rest their weary heads.

"What's a Doll's Function?" and "Holding Bowls." Dolls wrapped in a manner to reflect pipe-cleaner animals made after the loss of my large intestine, in bowls to rest their weary heads.