To prepare for the MFA Show, our curatorial team visited forty studios. In many, we became curious of the artist’s associated department because they were working with a wide range of media or using unexpected materials. To give a sense of the diversity of the practices at SAIC, I wanted to share my conversations with three artists’ on their experiences of working interdisciplinarily.

Abel Beruman, FVNMA

Abel grew up in Logan Square, but there was “no Starbucks back then.” He spent 18 years as a fashion photographer, shooting in New York, Miami, “all over the place,” before coming back to Chicago to attend SAIC.

As an MFA student, he works in different media and also choses to work with advisers with a range of practices and backgrounds, as well:

“My advisers are from all over. Mr. Mofffet (Video), Ms. LaToya Ruby Frazier (Photography), Mr. Eisenberg (Video), Ms. Harris (Painting). I pick my advisers based on their work and how it speaks to me. Not on resumes. I really don’t care if they had big museums shows, it’s all about the work. It’s all about their souls. For that, SAIC has the best faculty in the world.”

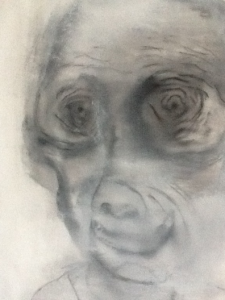

Even though Abel often works with oil paint, he describes his work in the language of video. When we met to talk about his work for the MFA Show, he described the presentation of his paintings as a film–arranging them in a long row, each work like a frame. When I asked Abel why painting, he remarked:

“I thought painting was the best way to capture my thoughts. Seeing 9/11…being across the street from the towers…I was speechless for a few months. And [I witnessed] my girlfriend battle cancer. I’m trying to capture with oil and canvas the anger and hopelessness I’ve felt.”

He went on to note that he does still works in various media, “oil on canvas and paper, video, 16mm Bolex, sound…”

Sammi Skolmoski, Writing

Sammi calls herself a “compulsive hobbyist.” When she was considering MFA writing programs, she felt trapped by having to choose to between one of two options – fiction writer or poet.

“A lot of my self-doubt came from an unrelenting thought that a lot of multidisciplinary artists have, which is: shouldn’t I just choose one of these things I enjoy and am good at and focus all of my attention on that one thing? And when Janet Desaulniers called me for my admissions interview she began by saying, ‘Hey, I bet you’re thinking: shouldn’t I just choose one of these things I enjoy and am good at and focus all of my attention on that one thing? Well DON’T! That would be the exact wrong thing to do. Instead, come here and do even more things.’ How could I say no to working with someone who addressed my neuroses before ever meeting me?”

The Writing Program at SAIC approaches writing as a studio practice. And for Sammi, that makes it “a perfect fit.” It has allowed her work to grow enormously.

“I would say I am 5% responsible for the way my practice has exploded, both in scale and ambition, since starting at SAIC, and faculty member and artist Dana [Carter] is responsible for the other 95%.”

When I asked Sammi about challenges of working in various media, she reflected:

“I tend to work both in and in between form in my writing, so sometimes critique panel feedback—from non-writers especially—can stall on the matter of labeling the work or assigning it a genre, instead of excavating content and process…I make it a priority to circumvent it in favor if the meatier parts… People also like to hear if/how the actual processes of writing and visual work overlap.”

I went on to question how she views the overlap between her visual and writing practices:

“I am interested in the metaphysical, the quantum, the ether, the other, the what-have-you, the it. With writing I can sketch it with adjectives, I can ponder it, I can describe everything around it, but I can’t touch it. I realized that if I want to touch it, I have to make it myself. And I want to represent it to the best of my ability, which requires deep consideration of materiality.

Something I’m very interested in both as a writer and artist is the question of accountability, and ways in which embroidery machines can be a sort of translation device, wherein interpretation is left completely up to them. It begins to feel more like a collaboration with another entity, rather than just using another piece of equipment.”

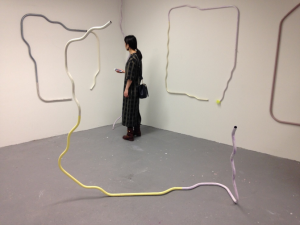

J. Michael Ford, Painting and Drawing

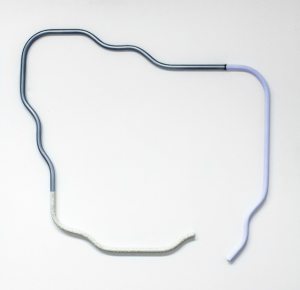

J. Michael’s background in sculpture is immediately apparent in his work. What’s less obvious is his background in photography. For me, this helps explain why these sculptures feel so different in photographs than they are in person.

“After [undergraduate], and not really having a studio, I spent a lot of time taking photographs that echoed [a bodily, personified] interpretation of objects I would find on the street. In addition, drawing was always a way to maintain a connection to the hand, and much of it had more to do with touch and mark making than articulating form, although a vocabulary also began to emerge through that over time. These combined to form much of what my work is today, both object based and linear while maintaining a bodily connection.”

Moving from a multimedia practice of sculpture, photography, and drawing into pursuing an MFA degree in Painting and Drawing was not an obvious transition for J. Michael. Even while trying to fit his practice into a medium-specific application process, he was curious about how his work could expand and push against those divisions.

“I wasn’t all that comfortable compartmentalizing my practice, and wasn’t really equipped with the language to gauge these divisions. I interviewed for both [Painting and Drawing and Sculpture] departments at SAIC and it seemed more a question of ‘fitting in’ to a culture than how my work operated…. Corny as it sounds, the optimist in me really liked the potential of expanding painting…. But the work really became about seeing it on its own terms, and although I can cite painting and its constraints, now that I’m here, I don’t get too mixed up in what it is.”

As for the feedback from other students and faculty, “as the work developed so did the conversation.” In its simpler forms, the work elicited formalist conversations. As J. Michael began adding glitter, jewelry, flowers, and other small objects to the works, the conversation shifted to one of identity. Both of these kinds of conversations still come up when J. Michael describes his work. And he’s not so concerned how you classify it.

“It is easy to say that it’s simply sculpture, but my concerns are with carving out and occupying an alternative space for the work to be experienced. It might be a subjective space, it might be emotional.”