This week in our SAIC Student Writing series Matthew Coleman (MA Art History 2015) blogs on John Gerrard’s large-scale digital works. He looks at the way Gerrard reveals the artificial natures of linear time and knowledge progression by bringing into question the provisional structures of power and networks of energy that facilitate our everyday existence.

John Gerrard joins Conversations at the Edge this Thursday March 5th, 6pm at the Gene Siskel Film Center.

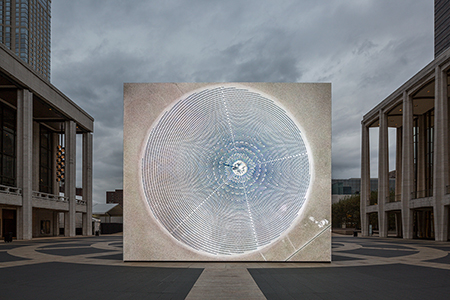

John Gerrard creates videos that are incredibly detailed virtual reconstructions of real locations. Take his recent Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada) (2014), for example. This video, which was installed at the Lincoln Center in New York City on a frameless LED wall, is a simulation of a day at a solar power plant in a remote Nevada desert. As I was flying to Los Angeles this summer to visit the Center for Land Use Interpretation, I saw a similar solar array reflecting the sun in the distance in the Mojave Desert.

So I was excited to see that Gerrard approached this subject of how companies are harnessing natural resources, but are also impacting the landscape around it to fuel nearby cities that are otherwise powered by giant dams, sometimes located across state lines. However, so convincing are his virtual reconstructions that my intrigue with his work has shifted to his process and the differences these recreations blur between a “virtual” reality, or a simulation, “nature,” which is also a simulation, and “reality…” which… may also be a simulation.

When I realized that it was hard to tell the difference between a video shot with a camera and one that was constructed on a computer, I began to think of the uncanny valley: the perceptive anxiety that occurs when features of something almost looks, but is not quite, natural. One of the more disturbing realizations of the uncanny valley can be seen in Robert Zemeckis’ The Polar Express from 2004. Moviegoers reported that it was “creepy” because of how eerily similar the computer generated characters were to the human actors. The actors’ motion and likeliness were captured by cameras and rendered by software to create a computer generated moving image. What was ultimately missing from the virtually mapped actors was a sense of life. Critics complained that these characters appeared lifelike, but were nevertheless soulless.

The uncanny valley is not a desirable outcome, but Gerrard evokes this perceptive quality to his favor, emphasizing the eerie simulations that are steadily replacing mass-media representations with simulations of the lifelike. His videos begin to beg the question, “What is real anymore,” especially when his chosen sites are all real. But as is with the case with Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada), this is a remote location, where the condition of being “out of the way” seems to allow his viewers to question the existence of such locations. They could be “out of this world,” which, when considering the virtual simulations, might not be too far off. There is nothing organic here.

In N. Katherine Hayles’ chapter “Simulated Nature and Natural Simulations: Rethinking the Relation between the Beholder and the World,” she argues against a dichotomy cut between nature and simulation. She proposes that the experiences with nature and a simulation may be more alike than previously thought. She writes:

Simulations work because they are natural as well as artificial, just as nature appears natural to us because we experience it through the simulacra provided by our bioapparatus. In a fundamental sense, nature and simulation meet in the dynamic and interactive cusp we ride when we experience the world.[1]

To leave behind our simulated apparatuses, to be modern luddites, and “to choose nature over simulation is not to escape from this dynamic but to reinforce it.”[2] To what extent do we fetishize “nature” or the ghosts of our pasts where things were “simpler”? I’m thinking here of the artist’s residency Mildred’s Lane. These turns, Hayles demonstrates, reinforces a dichotomy that forces us to stay within the perception that Nature represents edenic perfection, that it is a respite from our mediated, simulated lives that occur on the screens of our personal devices. This is a problem, especially when the concept of “nature” is just as much of a simulation or virtuality.

Gerrard’s videos play out this issue of the difference between “nature” and simulation, and perhaps the differences between them are no different. Perhaps it is important to view the world with an understanding of the ways in which it is constructed, with simulations standing in for natural depictions, or even vice versa. Perhaps one cannot tell the difference between a real place and a “real” one when looking at a screen or an image. Maybe to tell the difference, we have to ask what is fundamentally at stake when there is no perceptive difference between the natural and virtual, especially when reality becomes increasingly augmented.

[1] N. Katherine Hayles, “Simulated Nature and Natural Simulations,” in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, ed. by William Cronon (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996), 418.

[2] Ibid.

Matthew Coleman is a graduate student in Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He studies voids — from the perceptions of deserts as being empty and the imaginaries constructed of remote lands, to the ways in which we understand the Internet and digital culture as a utopian space within which we pour our energy. Currently he is writing his thesis on the Bonneville Salt Flats in western Utah. www.physicalcloud.tumblr.com