This thesis is an exploration of current and future stakes of conservationism and land management practices in the United States, and a series of inquiries on the relationship between the human and the non-human.

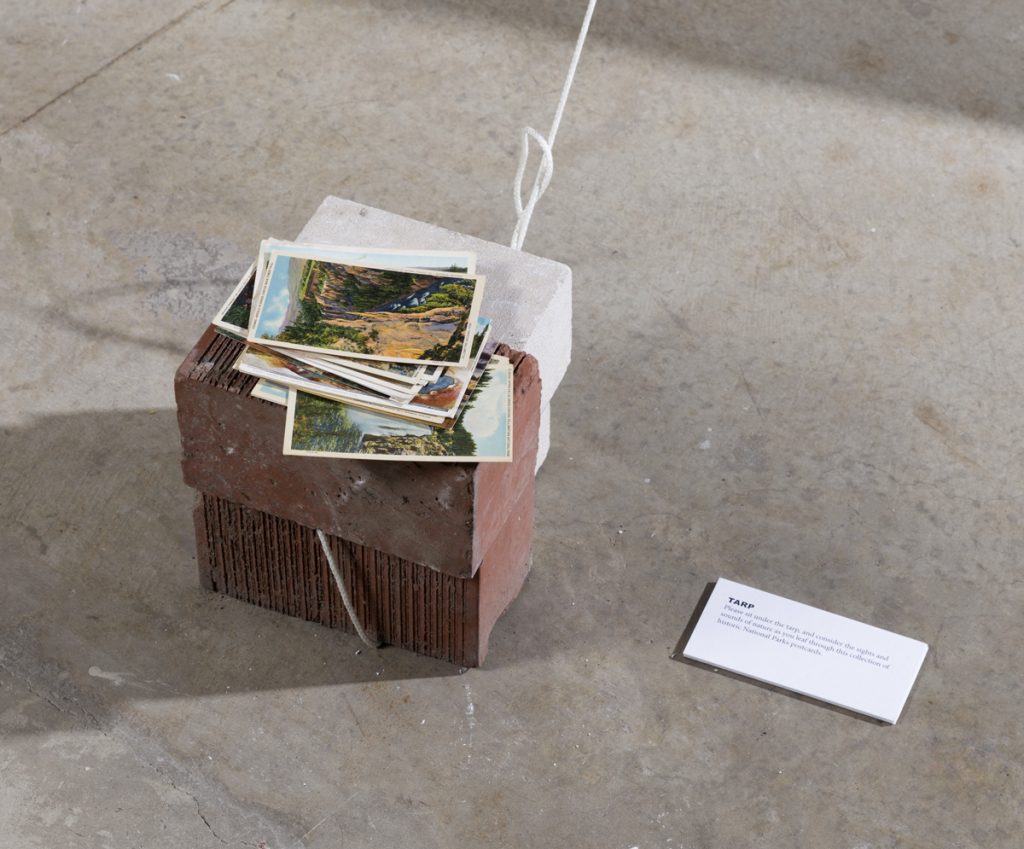

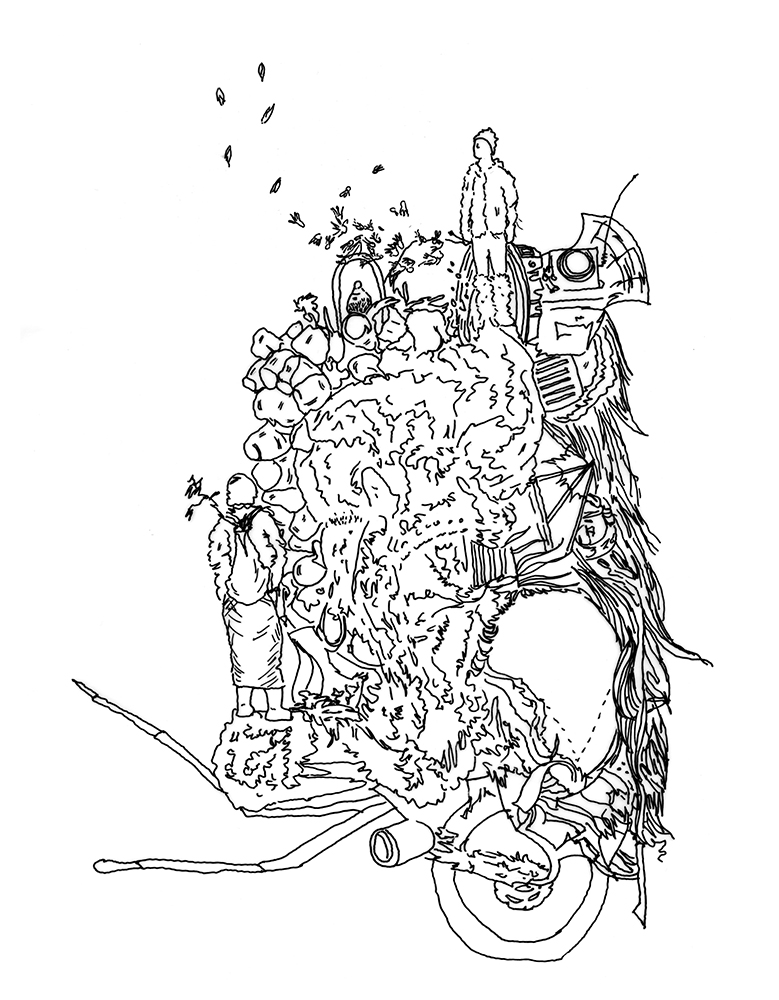

The thesis takes the form of a design ction–sited in the United States in the not- so-distant future, featuring a band of vigilante conservationists who travel across the country, maintaining open corridors for wildlife migration between eight major territories of American biodiversity. The group derives its philosophy and many of its tools, garments, and ways of living from the writings and inventions of 19th century writer and conservationist John Muir.The resulting production of tools, maps, vehicles, and other artifacts for this future community are a meditation and a commentary on the current tenuous state of biodiversity and humanity’s distorted relationship to the land, more than a “solution” or a fantasy. The intent of the this architectural thesis, as with all projective ction, is to create a confrontation with the motivations, tools, and protocols of a a future group of people who have decided to actively preserve the biodiversity of the United States, without waiting for systemic change or governmental facilitation.

The thesis is informed by research that explores how the American landscape has been designed for the consumption and development of the “ideal” American citizen, through the creation of scenic routes, parks, and lookouts since the early 19th century. This subject is expanded through the examination of current land management and conservation practices in the United States, and how these are directly impacting the plummeting biodiversity and declining land health on the continent. The ongoing and aggressive death of the non-human is in part due to a failure to communicate the necessity of wilderness, not just as the at, framed, aestheticized experience of the American Romantics, but as a function of existence.

One of the characters that has sprung forth in this investigation of the National Parks and the national imagination is John Muir, a Scottish-American mystic, conservationist, and scientist, who was instrumental in bringing about the National Parks. Muir is well known as an activist and a writer, but he also had an extensive practice as a designer, inventor, and architect. Through his relatively-unknown design work, he developed an ecological position— his projects (often clocks, reading machines, or measuring devices) encourage users to not just look out at the landscape as though looking at a place, without depth or weather, but to live in it, to experience a place’s forces acting on the body. His approach and his tactics are ultimately manifested in the intertwined wonder of the arti cial (something that is made by man or of man) and the natural, that is not of man, but tangent to it. We can call this nature, or we could call this the non-human. Muir’s life work was devoted to trying to stabilize the tangency, the kiss of the human and the non-human, and to prevent the moment when the human consumes the non-human, being on top of it instead of next to it.