Posted in Uncategorized on Tuesday, March 24th, 2020

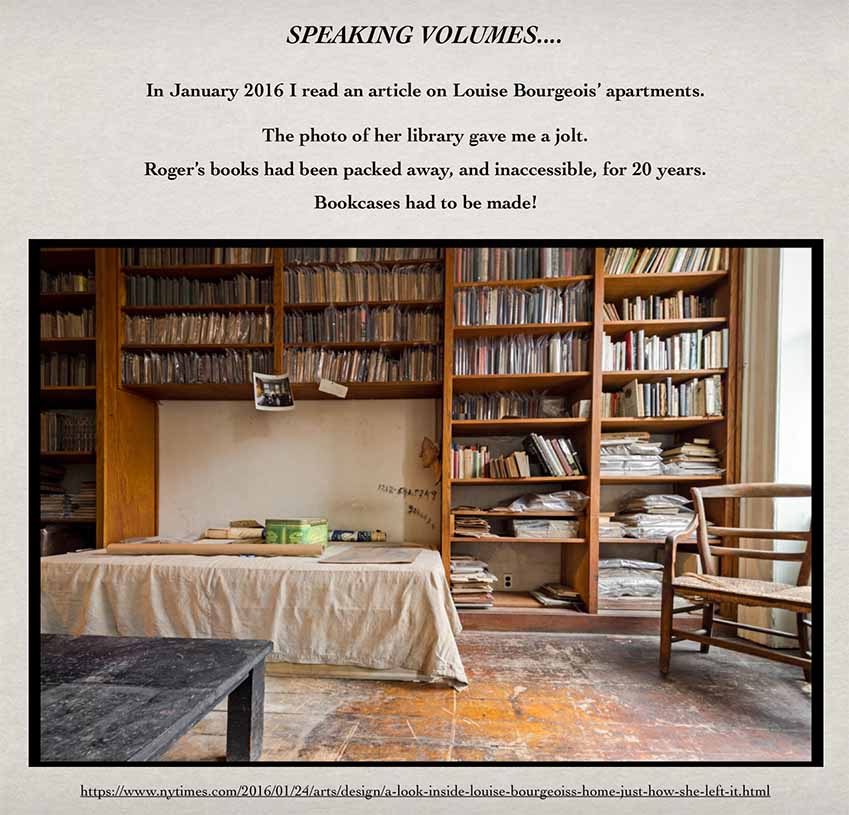

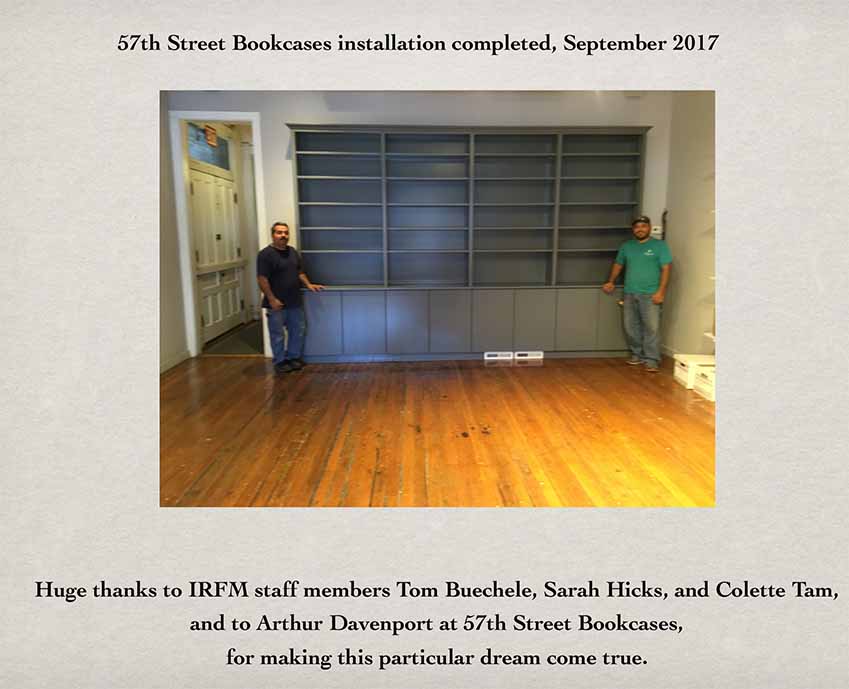

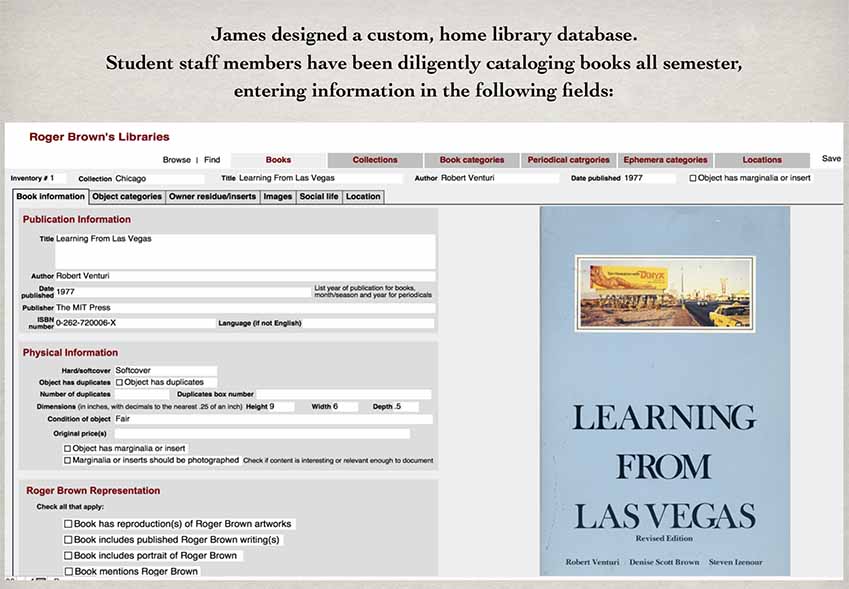

The Roger Brown Study Collection is closed until further notice, in accordance with SAIC’s campus closure, and for the health and safety of all.

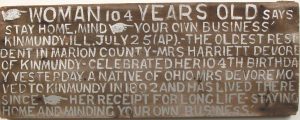

Mrs. Harriet Devore of Kinmundy, Illinois got it right: STAY HOME, MIND YOUR OWN BUSINESS.

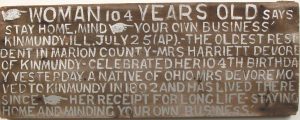

Roger Brown loved the work of Jesse “Outlaw” Howard (1885 – 1983), who animated his property on the outskirts of Fulton, Missouri, with signs and objects. Brown visited Howard and his “Sorehead Hill” environment in the early 1970s. He purchased several signs, and credited the rural artist with giving him permission to unleash his own independent voice, in his life and in his work.

We hope you’re enjoying the current directive to stay at home, and finding all manner of creative outlets.

Twenty seven years ago on a summer day in 1991, the Roger Brown mosaic at 120 N. LaSalle St. was unveiled. Standing confidently among Chicago’s portfolio of public art by famous artists – the Picasso, Calder’s Flamingo, Dubuffet’s Standing Beast, among many others – Brown’s two winged men soar high above the heads of pedestrians walking below on Chicago’s North LaSalle Street, across the street from City Hall. Against a brooding sky of dark clouds flecked with gold, the men appear to soar steadily upward, though those familiar with the tale of Daedalus and Icarus know what fate awaits the two men. Brown worked for almost two years to see the mosaic through to completion, beginning on the project while the building itself was still in the planning stages.

The property at 120 N. LaSalle St. has a modest history. Completed in 1891, an eight story office building was erected and called simply the Oxford Building. As in the building that occupies the site today, lessees were primarily law, architectural, financial, and real estate firms. The Oxford Building was demolished in 1935 to make way for a parking lot[1], at a time when the automobile was growing in popularity as an alternative and individualized form of transportation over mass transit.

120 N. LaSalle St. remained a parking lot until November 1989, when construction began on the current 40 story building in a project that would combine the functionality of the two previous developments, with the six bottom floors dedicated to parking, and the rest of the 390,000 square feet of rentable office space spread over the remaining 29 floors. The first project in Chicago by Los Angeles based developer Ahmanson Commercial Development, the building was designed by internationally renowned architect Helmut Jahn of the architectural firm Murphy/Jahn[2]. Jahn’s previous projects in Chicago included the 1982 addition to the Chicago Board of Trade as well as the Thompson Center, built in 1985. The building at 120 N. LaSalle remains a notable point of interest in the Loop not simply for its celebrity architect (Jahn is known for his flashy dress and demeanor), but also for its mosaic by our very own Roger Brown.

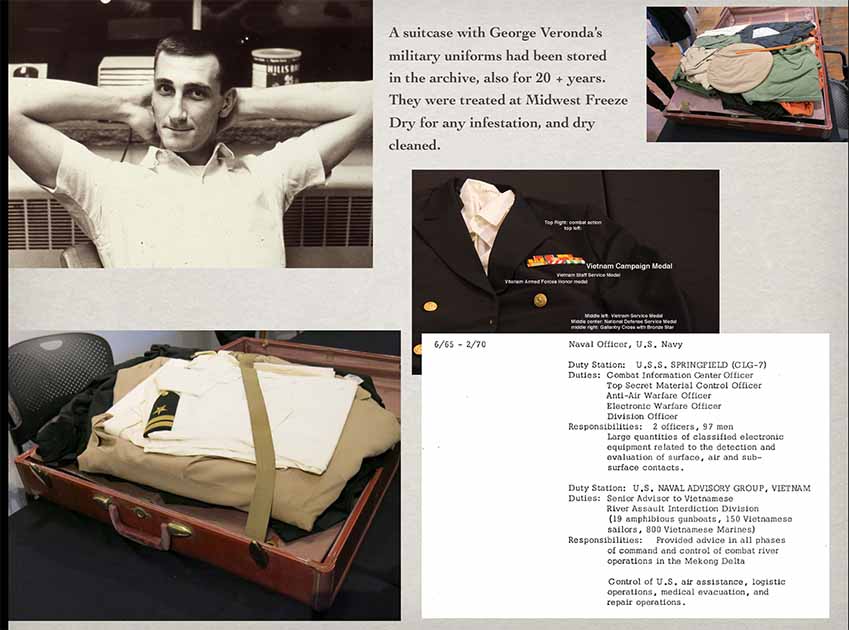

It was in late July 1989, before groundbreaking for the new building had taken place, when Brown was initially contacted about the possibility of a commission for the soon-to-be constructed building at 120 N. LaSalle Street[3]. Helmut Jahn was familiar with Brown’s work, as he had previously worked with George Veronda, Brown’s late partner, and had suggested Brown for the commission; Veronda and Jahn had been colleagues at the architectural firm of C. F. Murphy (of which Jahn later became a partner, forming Murphy/Jahn). Both Murphy/Jahn and the developer, Ahmanson Commercial Development Company, were supportive of Brown’s involvement with the project[4].

While at first deciding on the subject and overall feel of the mural, Brown took into account the building’s location, across the street from City Hall, where the mosaic would stand to greet the then Mayor Richard M. Daley and other local and state level politicians as they entered and exited city hall. Brown was cautious to avoid a subject that might feel dated with the passing of time; rather than make any direct commentary on current events or social issues, Brown sought a theme that would have the same impact in fifty years as the day it was created.

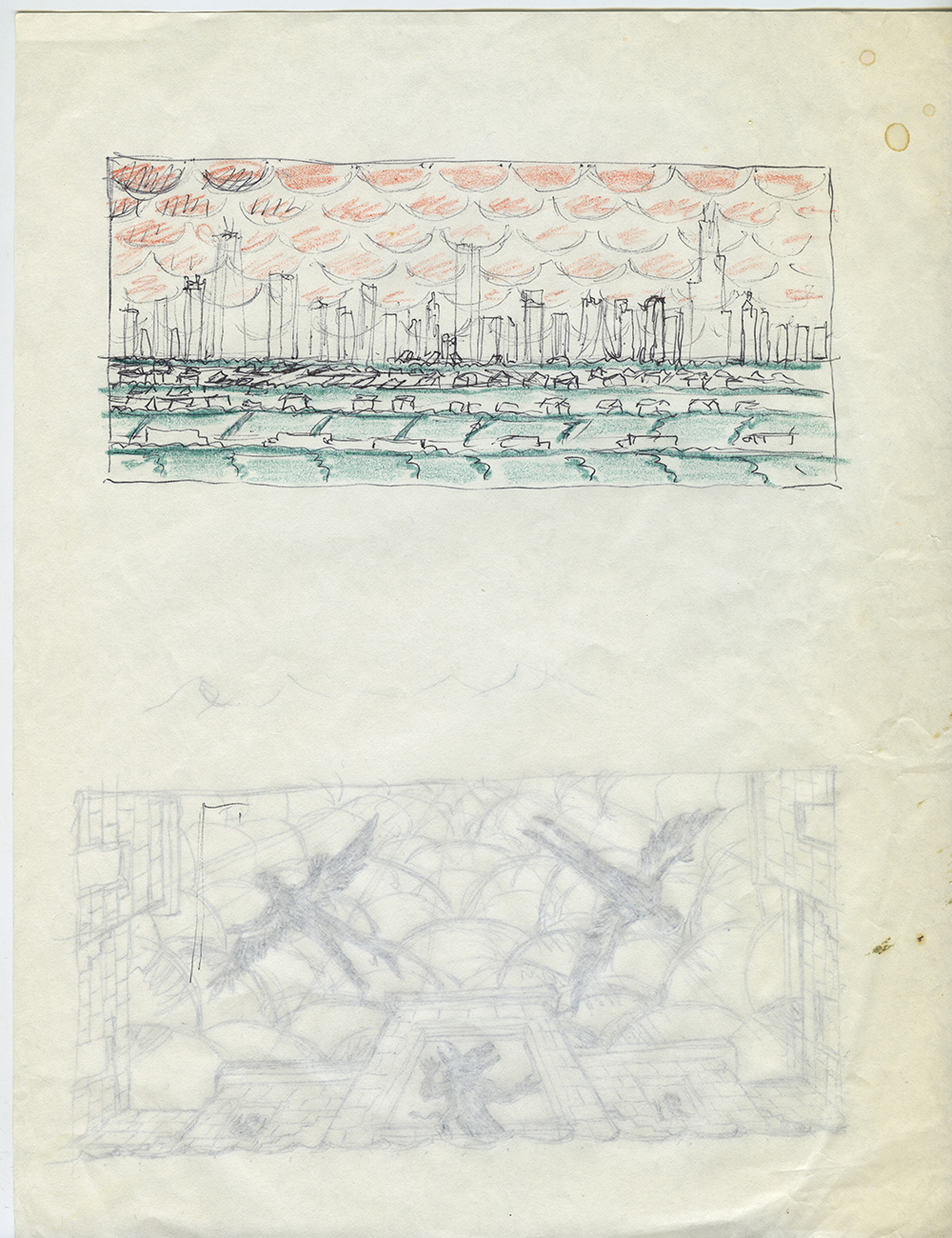

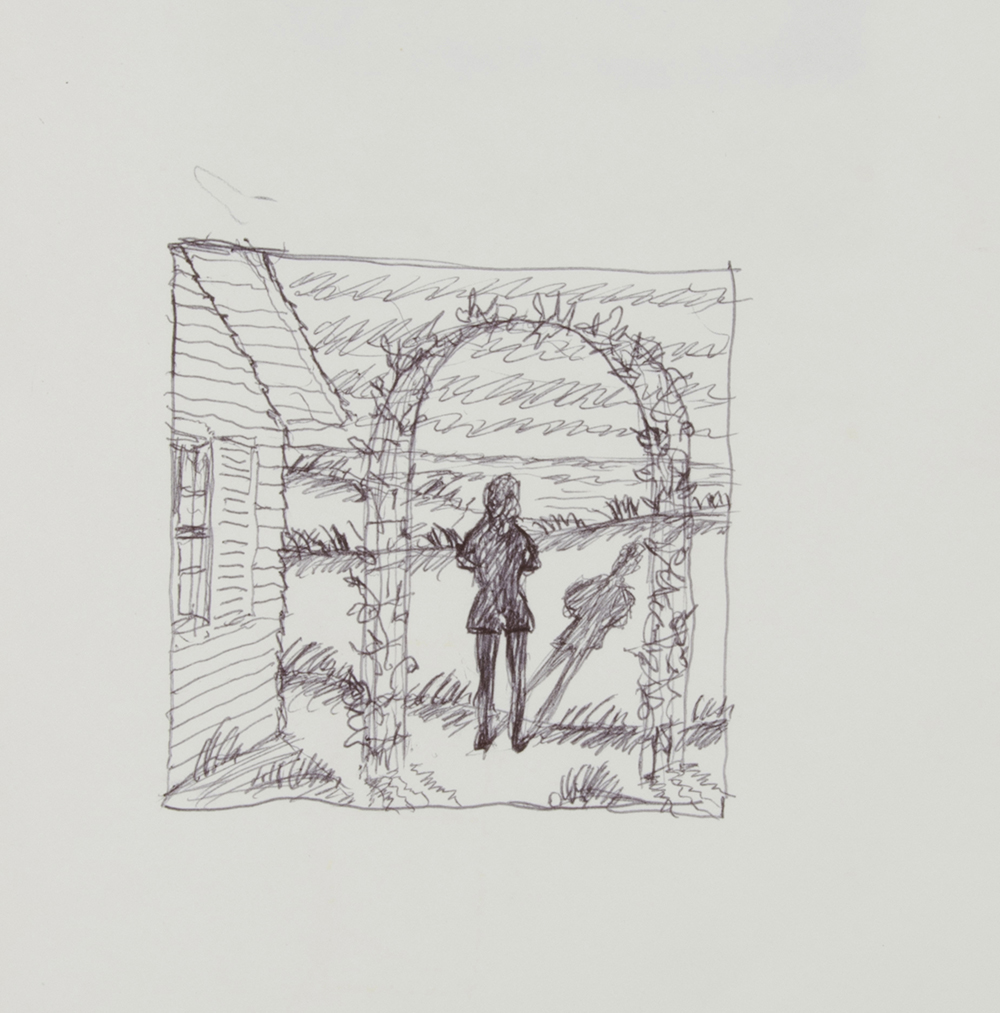

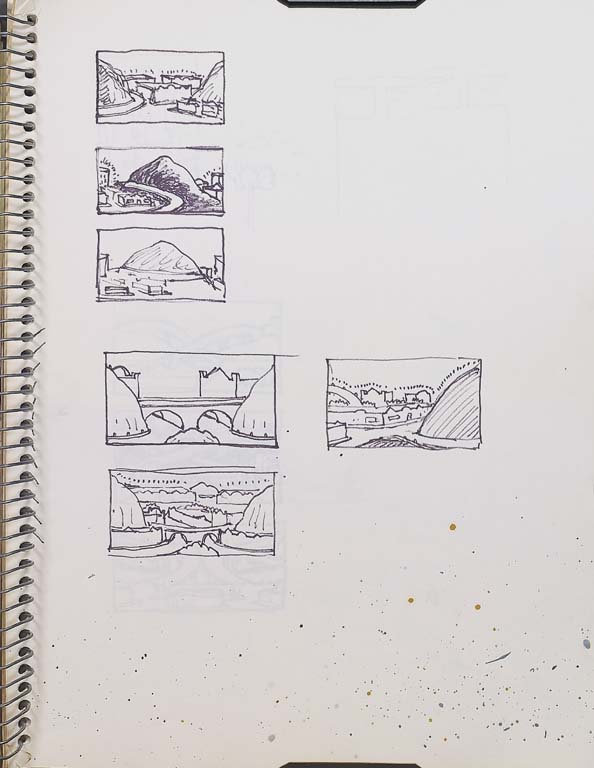

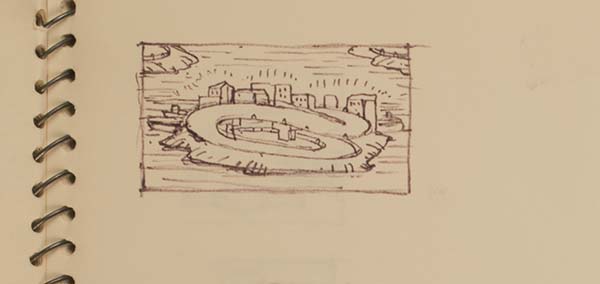

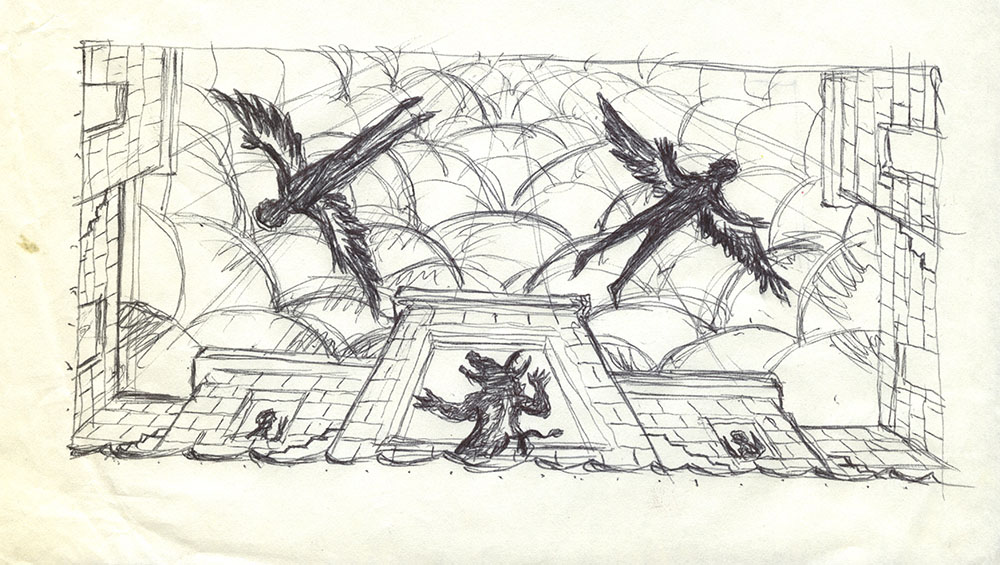

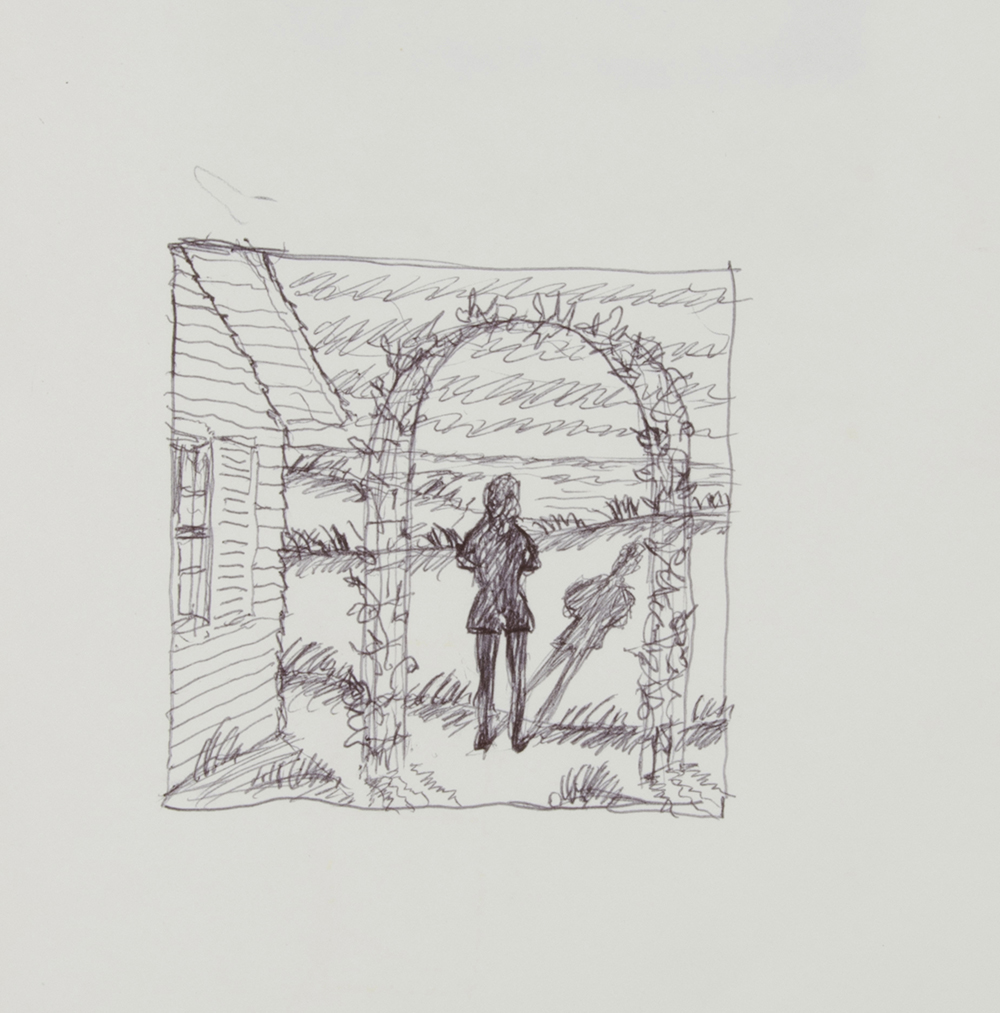

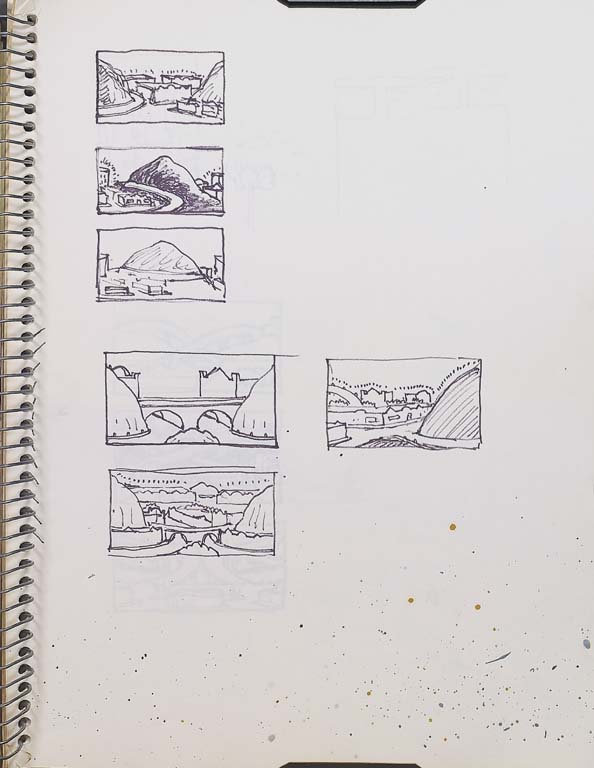

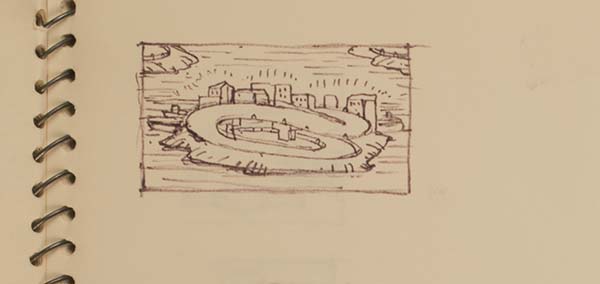

Figure 1: Roger Brown, “Untitled Sketch 05,” Pen on paper (n.d.), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

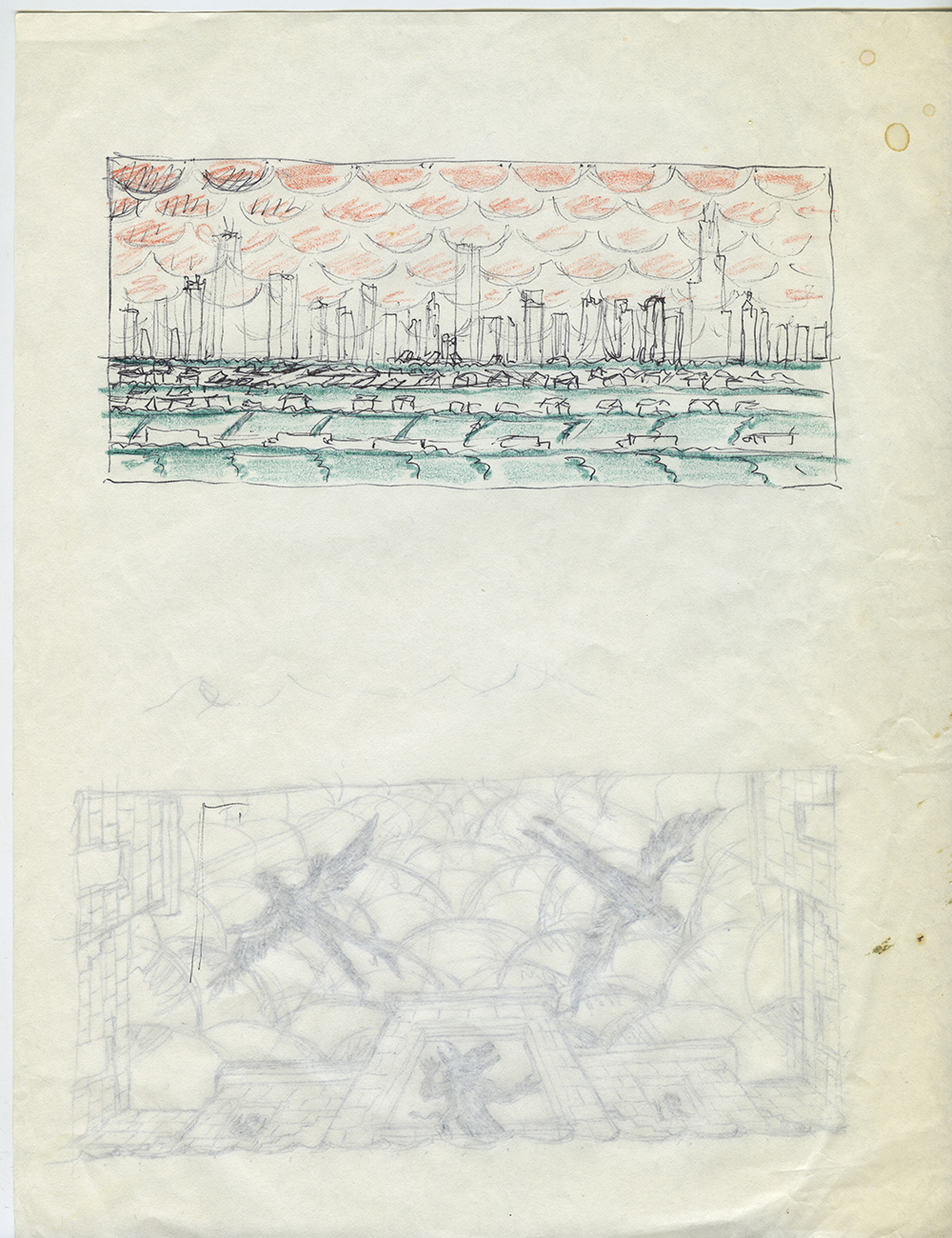

Brown felt the subject of the mosaic should both stand in context with and pay homage to Chicago’s rich architectural history. Initial ideas for the LaSalle mosaic featured the skyline of Chicago “rising from the ashes” of the fire (Figure 1), and share many similarities with City of Big Shoulders, another public commission Brown was working on at the same time (Figure 2). However in considering the concave ceiling upon which this mosaic would appear, high above the heads of pedestrians, Brown realized that incorporating imagery of the sky would be better suited for the location[5].

Figure 2: Preliminary sketches for City of Big Shoulders and the Arts and Science mosaics share the front and back of the page. Roger Brown, “Untitled Sketch 09,” Pen and ink on paper, (n.d.), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

In drawing connections between architecture and the sky, Brown came upon the tale of Daedalus and Icarus. The ancient Greek myth tells the story of Daedalus, the first architect, hired by King Minos of Crete to create a labyrinth that would contain the Minotaur. After a major event enraged King Minos and drove him to imprison Daedalus and his son Icarus on the island, Daedalus, ever the ingenious inventor, created wings of wax and feathers for him and his son so that they could take flight and escape the wrath of King Minos. Before their flight, Daedalus warned Icarus to “fly the middle path”—not too high, for the sun will melt the wax, and not too low, for the sea will wet the feathers, both resulting in failure. Ultimately, Icarus is so taken with the thrill of flying that he forgets his father’s advice and flies too close to the sun, melting his wings and plunging him into the ocean, where he drowns.[6]

Brown felt that this myth was an appropriate choice for the mosaic. Aware of Chicago’s lineage of corrupt politicians and nefarious innerworkings, Brown may have felt the tale’s cautionary stance against the perils of gloat and excess would be an appropriate image to greet politicians entering and exiting City Hall across the street. Brown also chose the tale for its celebration of technological innovation, where through grit and ingenuity Daedalus bestowed mankind with the gift of flight.[7]

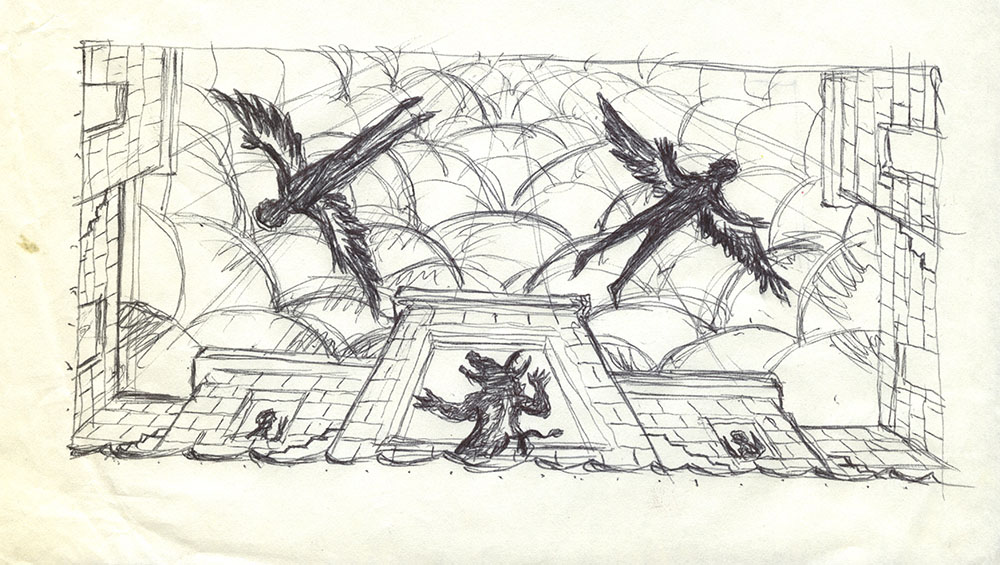

In beginning sketches for the LaSalle mosaic, color and composition varied greatly from sketch to sketch. Earlier drawings feature the failure of Icarus prominently, focusing on the precise moment when Icarus falls toward the sea. Several iterations of the sky were explored, with some versions featuring clouds in a dark red palette or dark dusty hues, and the direction of the clouds drifting downward in one, upward (as in the final composition) in another. In yet another sketch, the Minotaur threatens the mens’ escape (though the sequence of events would have been incorrect, as the reason Daedalus was imprisoned in the first place was because he aided Theseus in the defeat of the Minotaur). (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Roger Brown, “Untitled Sketch 09,” Pen on paper, (n.d.), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

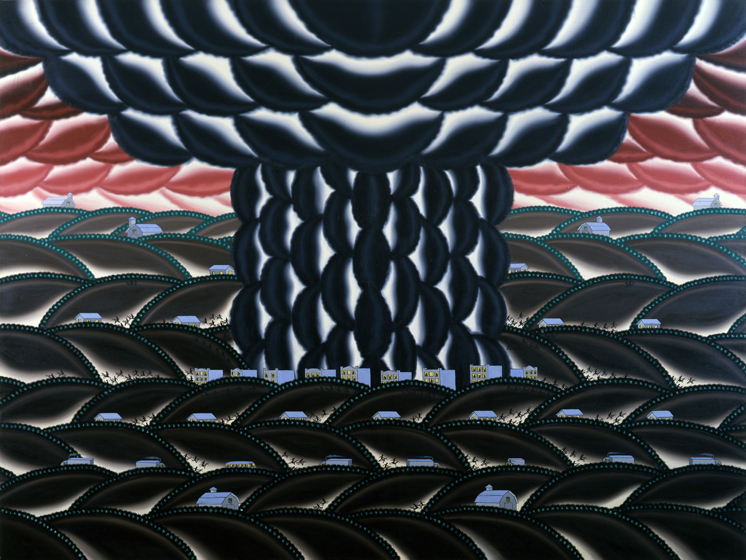

Once Brown settled on his subject, the initial proposals featured two silhouetted figures set against a sky of patterned billowing clouds in Brown’s signature style (Figure 4). Brown was well-known for his use of black silhouetted subjects in the foreground (which usually included people with the likeness of his mother and father, animals, and/or elements of nature, like plants) against a patterned background – repeating clouds and rhythmically undulating landscapes are recurring motifs.

Figure 4a: Roger Brown, “Arts and Science of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus, modello in Red,” Oil on canvas, (1989), private collection.

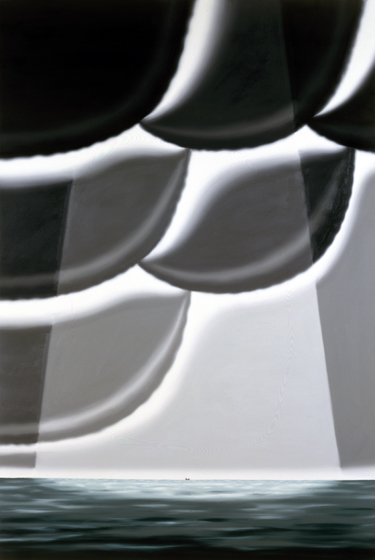

Figure 4b: Roger Brown, “Arts and Science of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus, modello in dark colors,” Oil on canvas, (1989), SAIC Roger Brown Estate and Kavi Gupta. (click to enlarge)

Responses to the first round of sketches were that the mosaic was too dark – both formally and metaphorically. Out of concern that the message would be seen as too critical or too cynical, it was requested that the composition be changed to be more “uplifting” in tone. Brown bristled at the initial feedback. In a letter to a colleague, Brown reflects:

“By giving up the strong gradation from darkest to lightest and by giving up the silhouetting of the figures one level is being eliminated from the work. That level is the level of mystery. I realize now that what those people saw as ominous is what I see as mystery and perhaps for more people mystery is not an acceptable experience! …What they don’t realize is that it is the mystery and formal elements what is drawing them in, and the mystery is created by the effects of illuminating clouds, people, trees, and other content from behind – by not illuminating everything from the front and therefore not giving all the information. By doing this the viewer is forced to fill in some of the information himself.”[8]

Brown adjusted the tone and focus of the composition in response to the feedback. Additionally, after researching his subject further, Brown chose instead to draw upon Joseph Campbell’s commentary on Daedalus’s success and Icarus’s failure in his book History of Myth:

“For some reason, people talk more about Icarus than about Daedalus, as though the wings themselves had been responsible for the young astronaut’s fall. But that is no case against industry and science. Poor Icarus fell into the water–but Daedalus, who flew the middle way, succeeded in getting to the other shore.”[9]

Brown decided instead to highlight the beginning of the tale, just after the two men begin their flight. Interpreted as a moment brimming with hope and optimism, their flight is a celebration of science and technology, and the innovation that made such a feat possible. To accommodate the request of a more colorful and “illuminated” rendering of his subjects, Brown moved the light source to the front of the composition, illuminating both the foreground and background, rendering his subjects in full color (though, in Brown’s words, removing “the mystery” of the composition)[10].

Despite this turbulent start, Brown ultimately felt satisfied with the shift. He later wrote a colleague stating, “I loved doing the mosaic and I even think the initial process of compromise and changing the design was much for the better. I read recently that Louis Kahn did the same thing for Jonas Salk for the Salk Institute in La Jolla when Salk experienced an uneasiness with Kahn’s first design. So if Louis Kahn can do it and end up with a better design, so can I!”[11]

In the final composition, titled Arts and Science of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus, two men soar upward in unison into a sky of billowing clouds. Just above the reaches of the sea, the men appear steady and calm in their ascent. Devoid of any signs of movement (their robes lie smooth and creaseless against their bodies, their hair perfectly stiff), the figures appear to float against the sky, suspended. The tops of the clouds are flecked with gold, carrying the eye upwards and away from the dark sea below, casting a feeling of optimism on the overall composition. At the very right of the composition Brown designed a trompe l’oeil rendering of the H-shaped column that would stand in front of the mosaic once installed. In the final mosaic, the column is rendered using the same granite that clads the face of the building. The direct reference to the building on which the mosaic is installed gives the mosaic context and grounds this cautionary tale in the present moment, bridging the ancient and modern worlds. It also is a nod to its specific location, as if to say, this placement is not incidental. (Figure 5)

Figure 5: The final composition. Brown was especially careful to pay attention to detail in this painting as this would be the final image used by the mosaic studio to enlarge and reproduce in glass tesserae. Roger Brown, “Arts and Science of the Ancient World: The Flight of Daedalus and Icarus,” Oil on canvas, (1990), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

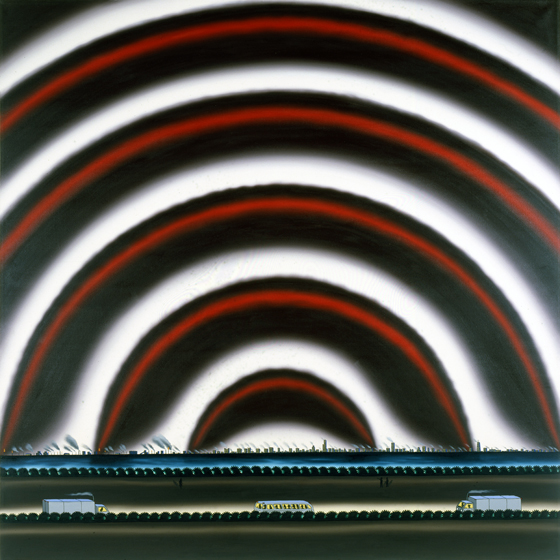

While the initial contract was for the design of the exterior mosaic, the project grew to include a smaller mosaic for the interior of the building. Titled Arts and Science of the Modern World: LaSalle Corridor with Holding Pattern, the smaller mosaic reflects the outdoor mosaic and again connects myths from the ancient world to reality in modern world. The mosaic itself is a stylized depiction of a modern-day view down the LaSalle street canyon, with the Chicago Board of Trade standing tall at the horizon. In this mosaic, Brown returns to his signature use of black silhouetted figures and simplified buildings rendered in various shades of cool grey. Set against the same sky where Daedalus and Icarus once flew, planes circle overhead waiting for their turn to land at O’Hare. The myth of human flight is now realized.

While the mosaics are a direct nod to Chicago’s legacy of architectural innovation, the works also contain autobiographical parallels to Brown’s own life and his relationship with his life partner, George Veronda (1941-1984), and can be interpreted as an ode to Veronda and the important role he played in Brown’s life. In Brown’s depiction of Daedalus and Icarus, rather than portraying a demonstrable age difference of a father-son relationship, the two men appear to be the same age, and decidedly similar in appearance. In discussing the mosaics (both of the winged men and airplanes in holding pattern) with Mary Mathews Gedo, psychoanalyst-turned-art historian and publisher of several books that employ a psychoanalytic approach to art criticism, Brown remarked that for him the two men “soaring away [served] as symbolic of our trips together”[12].

Veronda had an immeasurable influence on Brown’s own development as an artist, cultivating Brown’s interest in architecture. After all, it was through Veronda that Brown had become familiar with Helmut Jahn and his work. In Brown’s writing, For George: An Autobiography in Pictures, a memoir about time spent with his partner, Brown wrote, “George introduced me to the importance of Mies van der Rohe and to the style of contemporary Chicago architecture… and drew my attention to the importance of the pattern and repetition”.[13]

Through Veronda’s influence, Brown began to draw connections between the midwestern landscape and architecture. After a formative trip together to the Black Hills of South Dakota, the artist “began to treat landscape in an architectural manner, creating very formal patterns and placing cities, objects, and people within this setting”.[14] In Brown’s own words, “This observation [represented] an exciting expansion of my own work and became a dominating factor” in his art from that point forward.[15]

The mosaics were realized and installed by Crovatto Mosaics, a studio in Spilimbergo, Italy. Brown communicated closely with Constante Crovatto, head of the studio, to ensure a smooth interpretation of the design. In a letter to Crovatto, Brown insisted, “I prefer they have the quality more related to the earlier Italian “primitives” (so-called): Giotto, Masaccio (sic), Duccio, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca. I even look forward to the increased stylization which will inevitably result from the mosaic technique.”[16]

A team of six people took four months to complete the 27’ x 54’ mosaic[17]. Workers prepared the mosaic in sections, to be shipped overseas assembled on site (Figure 6). During this time, Brown flew to Italy for ten days near the end of the completion of the mosaic to conduct a final review of the project. Back in Chicago, a team of Crovatto employees were flown in for the installation and took three weeks to complete. The final exterior mosaic consisted of almost 1 million individual tiles.

Figure 6: Photos taken by Brown of the mural construction during his trip to Italy. (1991), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

The mosaics were unveiled on July 31, 1991 in a ceremony that was attended by friends, collectors, and local officials. Later that year, on November 12, 1991 the grand opening for the entire 120 N. LaSalle Building was held, almost exactly two years after ground was broken on the site (Figures 7, 8).

The mosaics at 120 N. LaSalle were the first of several public commission for Brown. Happy with his first experience working with Crovatto mosaics, specifically their successful translation of his style into the mosaic medium, Brown worked with Crovatto to complete two other public commissions, Twentieth Century Plague: The Victims of AIDS, completed in 1995 for the lobby of the Foley Square Federal Center in Manhattan, and another Chicago commission in 1997, Hull House, Cook County, Howard Brown: A Tradition of Helping, for the lobby of the Howard Brown Health Center.

Figure 7: Photo of mosaic as installed at 120 N. LaSalle Street. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

Figure 8: Photo of interior mosaic as installed in the lobby of 120 N. LaSalle Street. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago. (click to enlarge)

From the very beginning, the 120 N. LaSalle Building was steeped in Chicago culture. Both architect and artist were men of international stature who made a home and carried great influence in Chicago: Helmut Jahn, whose numerous architectural projects shape Chicago’s urban landscape (and will continue to shape the landscape as Jahn’s firm is still designing projects for the city), and Roger Brown, among the most celebrated and well-known Chicago artists. Brown’s contemporary use of classical subject matter fits in with Chicago’s collection of classical revival style architecture, and marries the contemporary moment with the past, situating 120 N. LaSalle Street comfortably within Chicago’s portfolio of public art and lineage of distinguished architecture.

Alessandra Norman, 2018

[1] Steve Kerch, “Apartments Hold Investment Allure”, Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1992

[2] Ahmanson Commercial Development Company, “Installation Of Roger Brown Mosaic At 120 North Lasalle Street Adds To City’s Public Art Collection”, News release, Chicago, IL, July 31, 1991, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_009_003

[3] Tamara Thomas, “Thomas To Brown: July 31, 1989”, Letter (1989), Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago

[4] Thomas, “Thomas to Brown: July 31, 1989”

[5] Andrew Gottesman, “Pieces Fall Into Place For Craftsman”, Chicago Tribune, August 02, 1991.

[6] Edith Hamilton, Mythology, 14th printing, (New York: 1961), 139-40 and 151-2, as referenced in Mary Gedo, “Public Art/Private Iconography: Roger Brown’s Transformation Of The Myth Of Daedalus And Icarus”, Art Criticism 11, no. 2 (1996): 53.

[7] Roger Brown, “Untitled Notes”, Notes, (n.d.), Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_003_003.

[8] Roger Brown, “Brown to Thomas”, Letter, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_001.

[9] Mary Gedo, “Public Art/Private Iconography: Roger Brown’s Transformation Of The Myth Of Daedalus And Icarus”, Art Criticism 11, no. 2 (1996): 41.

[10] Brown “Brown to Thomas”

[11] Roger Brown, “Brown to Thomas”, Letter, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_003.

[12] Roger Brown, “Brown to Gedo”, Revisions/annotations to text by Gedo, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_010_007.

[13] Roger Brown, “For George” (unpublished memoir), transcription of hand-bound book on Arches paper, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago: 2.

[14] Brown, “For George”: 2.

[15] Brown, “For George”: 3.

[16] Roger Brown, “Brown to Crovatto”, Letter, Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_002. *my best guess, handwriting was difficult to discern

[17] Gottesman, “Pieces Fall Into Place For Craftsman”

Bibliography

Brown, Roger. “For George” Unpublished memoir, transcription of hand-bound book. Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Brown, Roger. Letter from Brown to Constante Crovatto, 1990. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_002.

Brown, Roger. Letter, attachment with revisions/annotations to text originally by Gedo from Brown to Mary Gedo, 1990. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_010_007.

Brown, Roger. Letter from Brown to Tamara Thomas, 1989. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_001.

Brown, Roger. Letter from Brown to Tamara Thomas, 1989. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_002_003.

Brown, Roger. Miscellaneous notes on the LaSalle mosaic. Roger Brown Study Collection, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_003_003.

Gedo, Mary “Public Art/Private Iconography: Roger Brown’s Transformation Of The Myth Of Daedalus And Icarus”, Art Criticism 11, no. 2 (1996): 41.

Gottesman, Andrew. “Pieces Fall Into Place For Craftsman.” Chicago Tribune, August 02, 1991.

Hamilton, Edith. Mythology, 14th printing, (New York: 1961), 139-40 and 151-2, as referenced in Mary Gedo, “Public Art/Private Iconography: Roger Brown’s Transformation Of The Myth Of Daedalus And Icarus”, Art Criticism 11, no. 2 (1996): 53.

“Installation Of Roger Brown Mosaic At 120 North Lasalle Street Adds To City’s Public Art Collection”, News release, Chicago, IL, July 31, 1991, Ahmanson Commercial Development Company. Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_009_003.

Kerch, Steve. “Apartments Hold Investment Allure.” Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1992.

Thomas, Tamara. Letter from Thomas To Brown, 1989. Roger Brown Study Collection Archive, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, RBA_043_001_001.

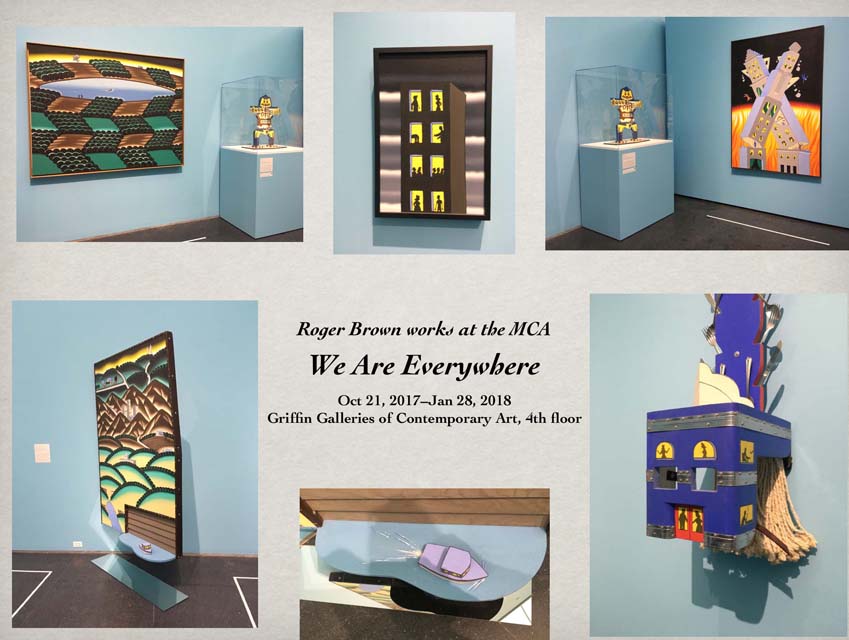

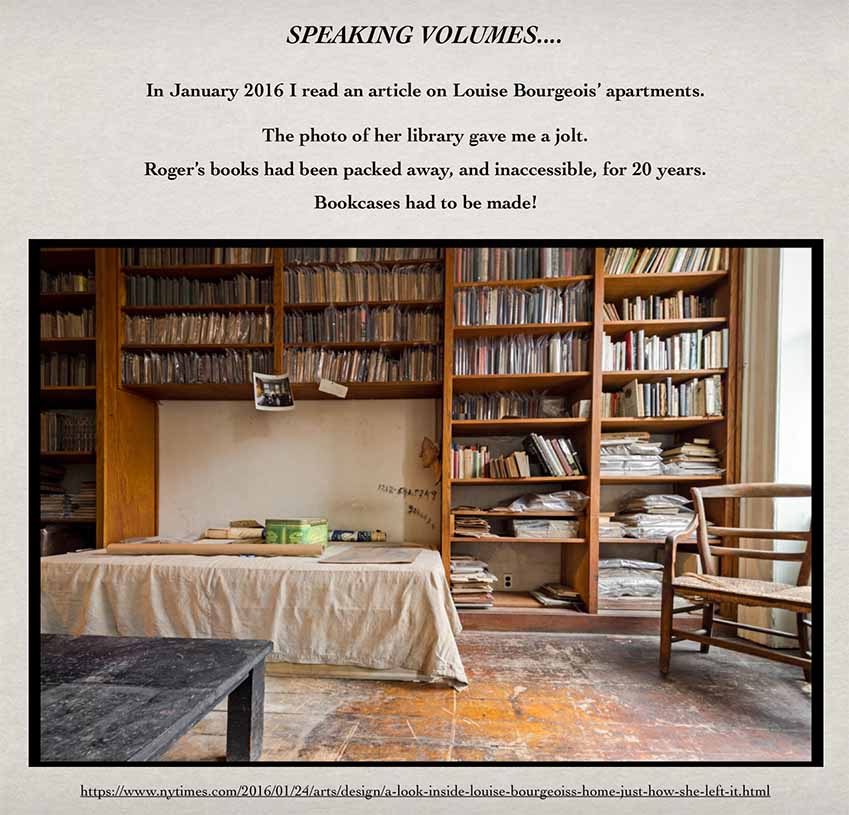

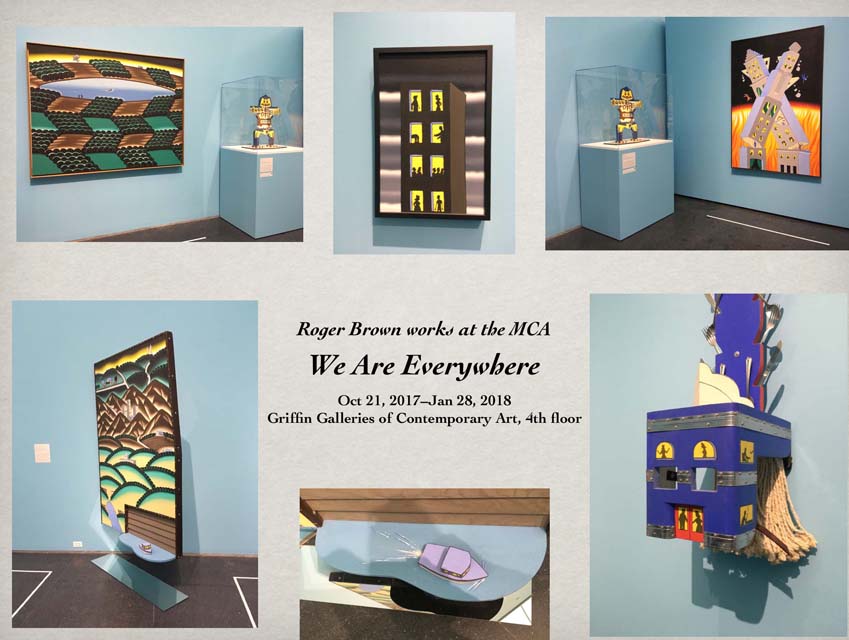

Posted in Uncategorized on Friday, December 22nd, 2017

Posted in Uncategorized on Wednesday, November 22nd, 2017

Today, (November 22, 2017) is the 20th anniversary of Roger Brown’s death, also the 54th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

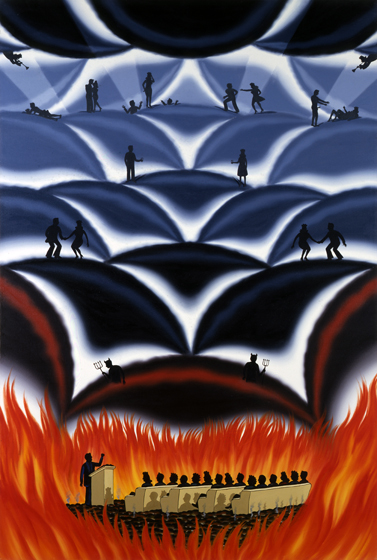

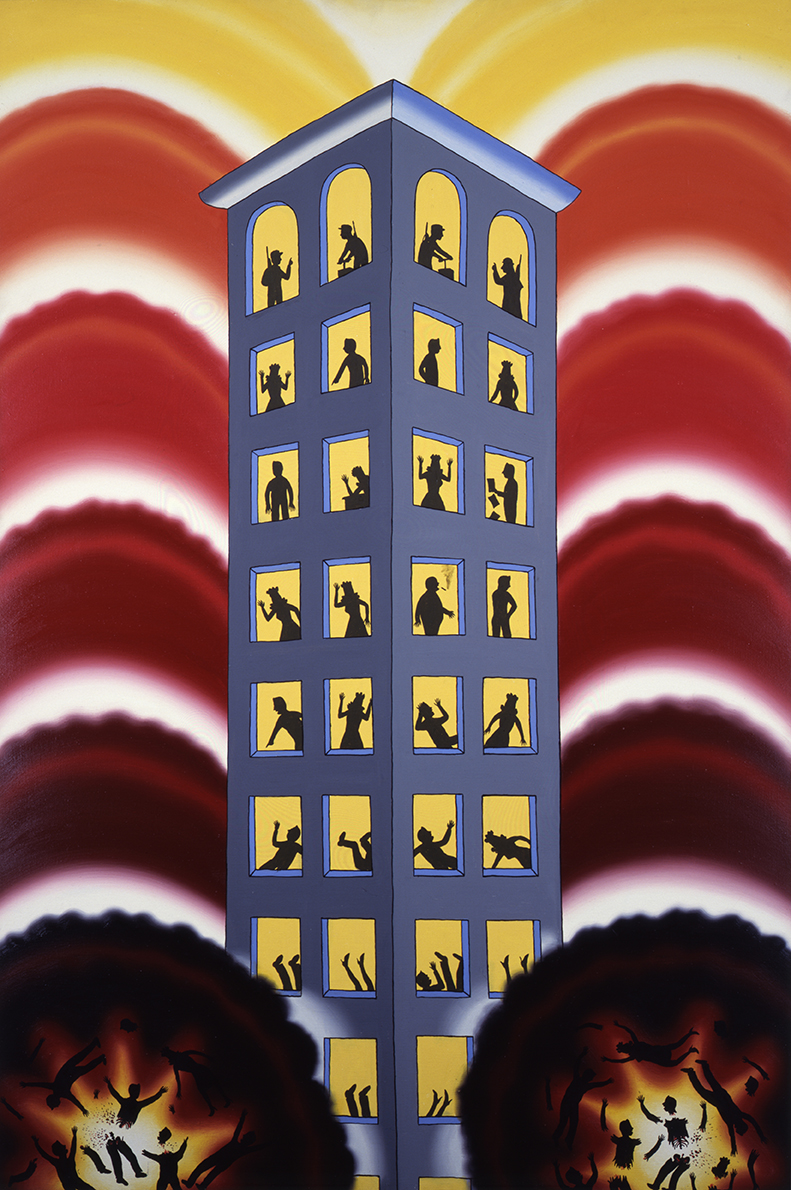

Reflecting on Brown’s extraordinary career, his insightful, incisive depictions of the world, and his exceptionally generous gifts to the School of the Art Institute, following is a modest tribute, a selection of 20 works––a small sampling from over 900 possibilities.

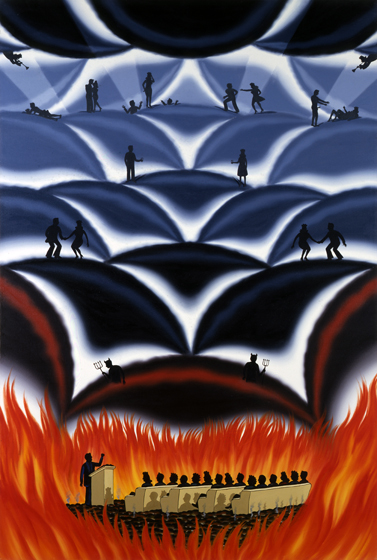

Assassination Crucifix, 1975, oil on wood construction, 70 x 46 in.

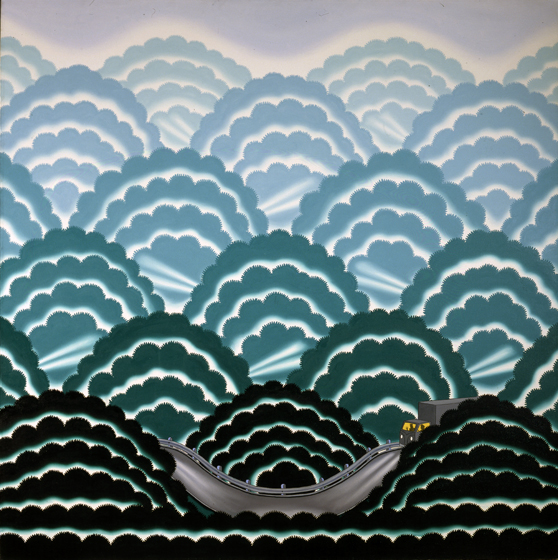

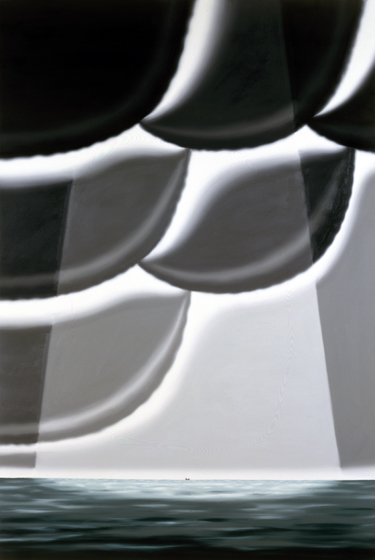

Misty Morning, 1975, oil on canvas, 72 x 72 in. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh. For Barbara Rossi.

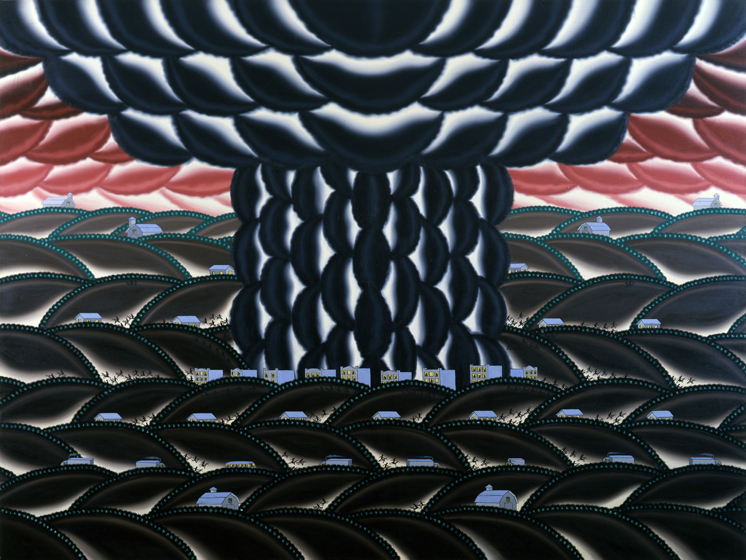

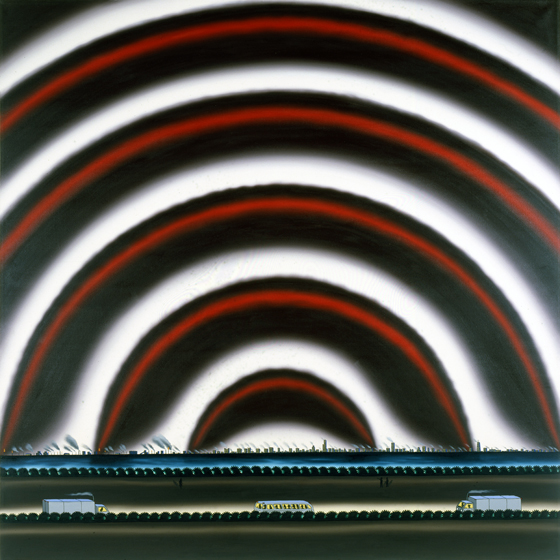

Chain Reaction (When You Hear This Sound You Will Be Dead), 1977-78, oil on canvas, 72 x 96 in. Castellani Art Museum of Niagara University, NY. For James Connolly.

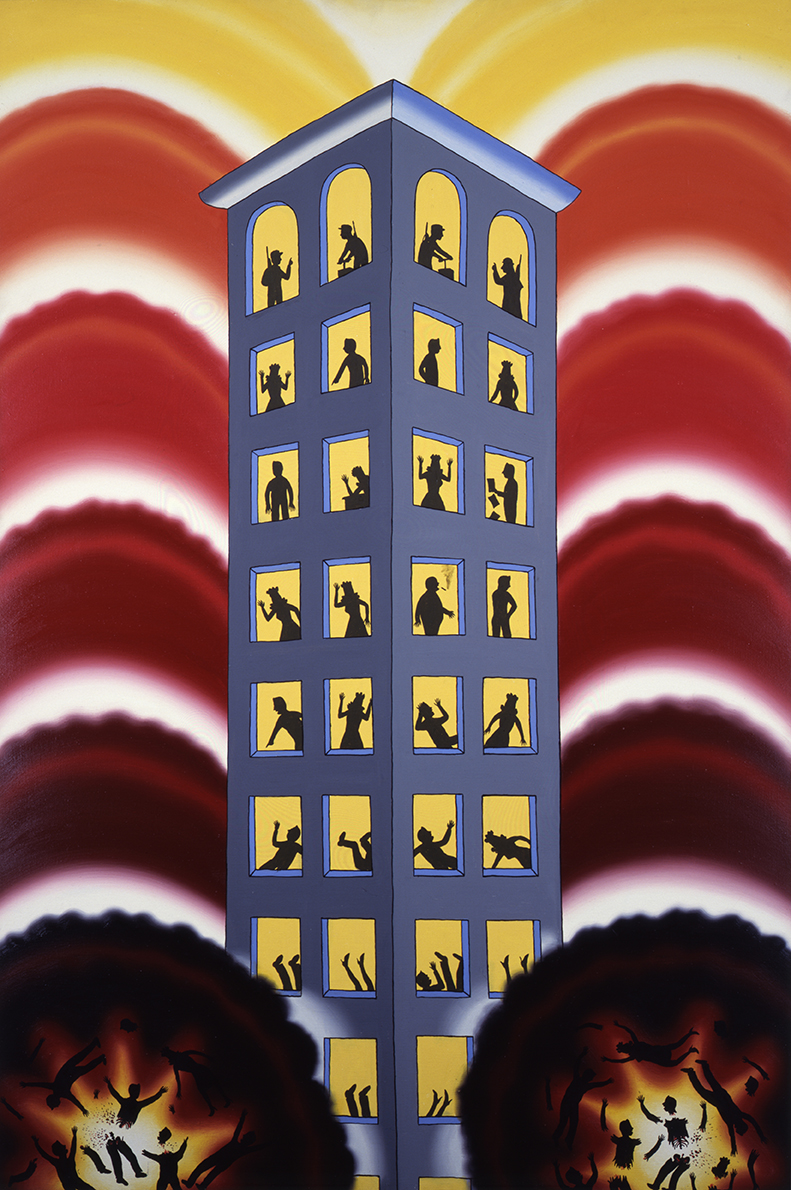

The Devil’s Surprise, 1980, oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in. For Greg Brown, who, if he could own any one of his brother’s paintings, would own this, as it so aptly expresses the Brown brothers’ feelings about reversing the “church hurt” they experienced.

Lake Effect, 1980, oil on canvas, 72 x 72 in. Roger Brown Estate and Kavi Gupta. For Jana Wright.

Memory of Sandhill Cranes, 1981, oil on canvas, 60 x 96 in.

IRA PLO FALN, 1982, oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in.

Peach Light, 1983, oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in. Roger Brown Estate and Kavi Gupta.

American Landscape with Revolutionary Heroes, 1983, oil on canvas, 84 x 144 in., North Carolina Museum of Art.

The Final Arbiter, 1984, oil on canvas, 72 x 108 in. Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College. For George Veronda.

Arrangement in Blue and Gray: The Artist and His Friend Fishing, 1985, 72 x 48 in. Roger Brown Estate and Kavi Gupta

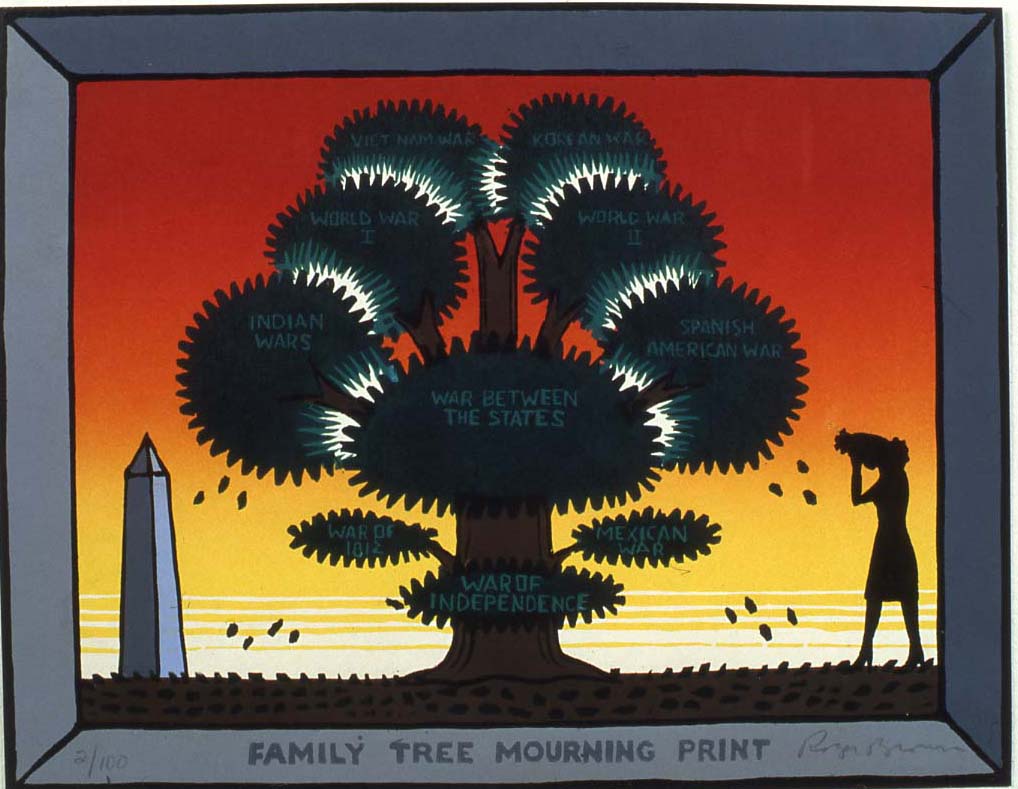

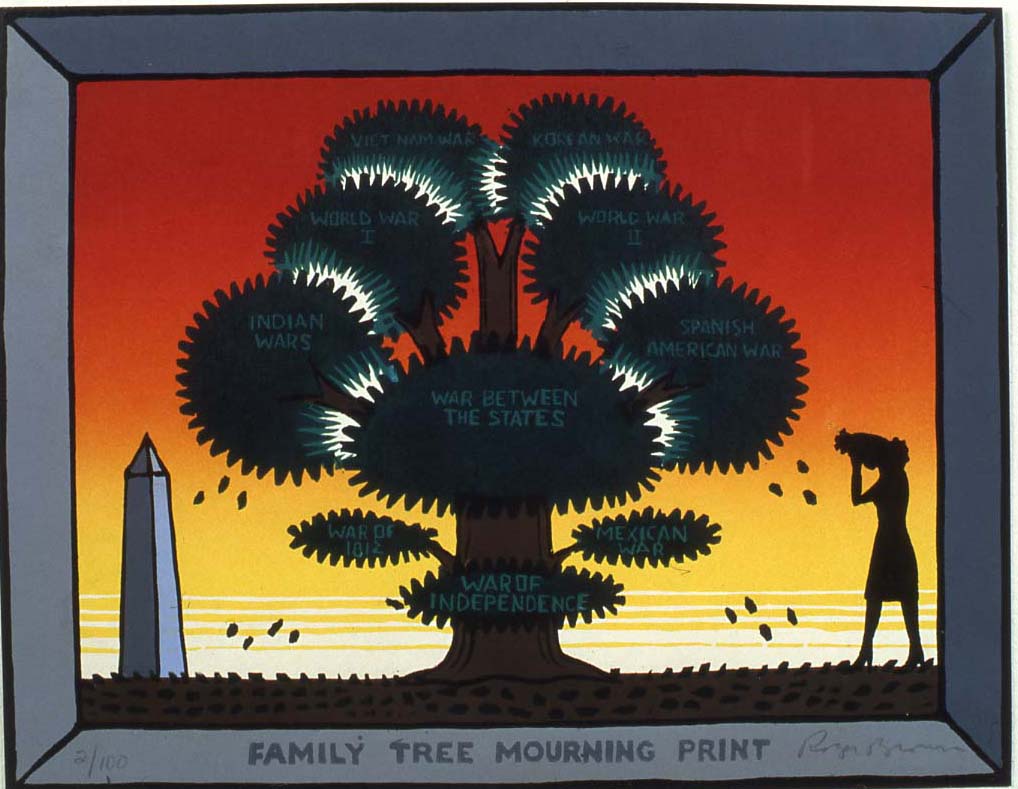

Family Mourning Tree Print, 1987, color relief print, 10 3/4 x 13 3/4 in.

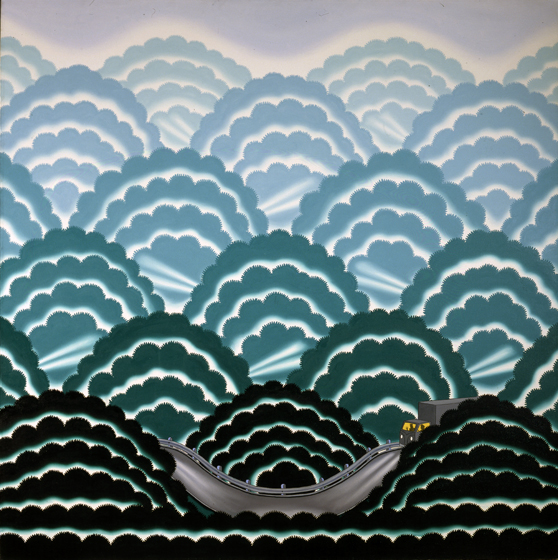

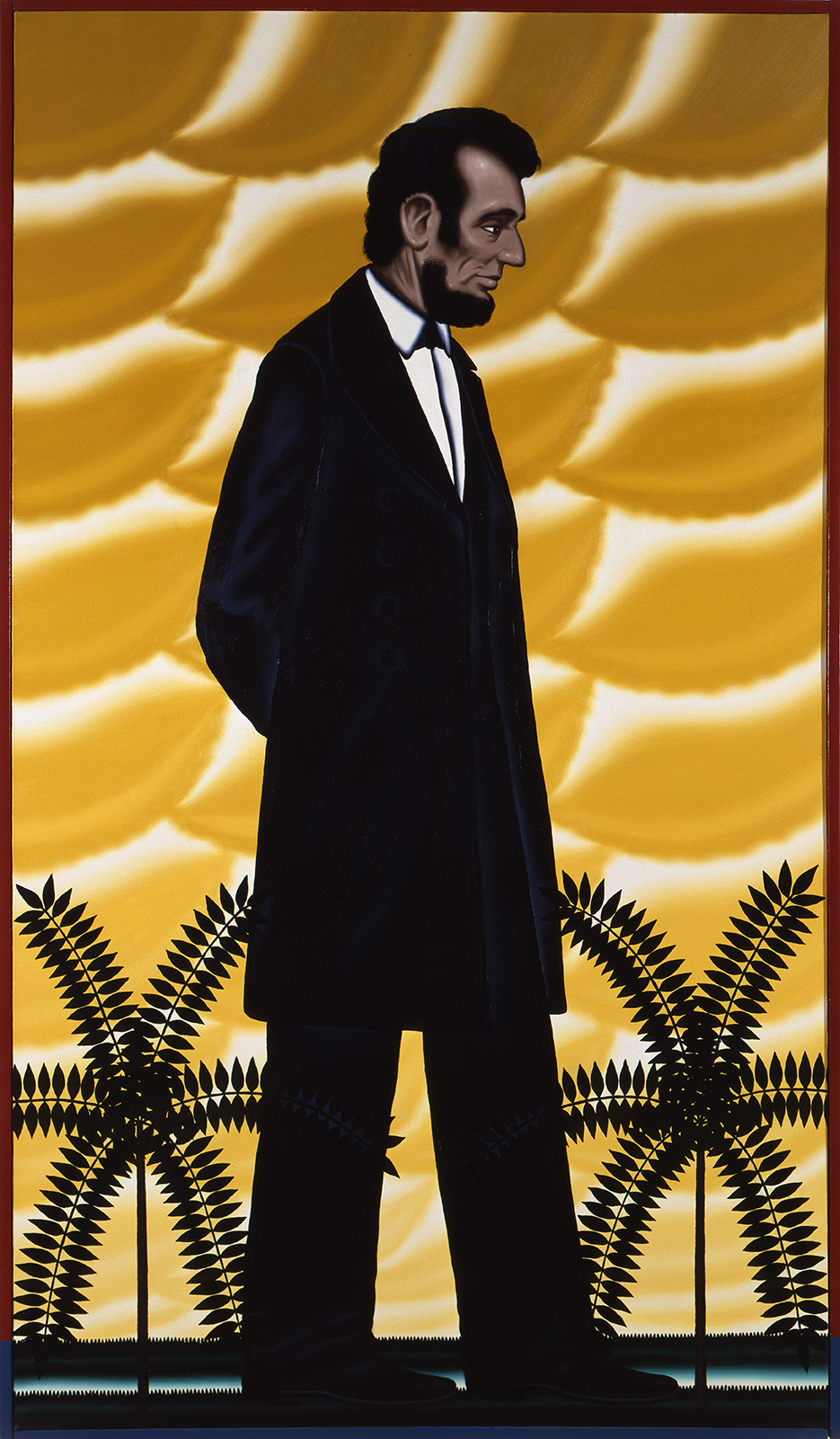

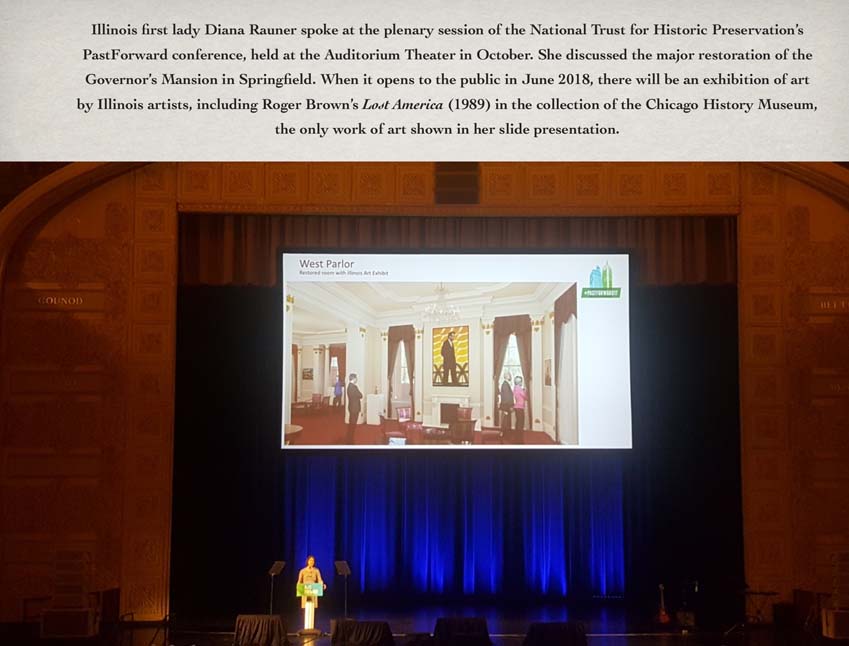

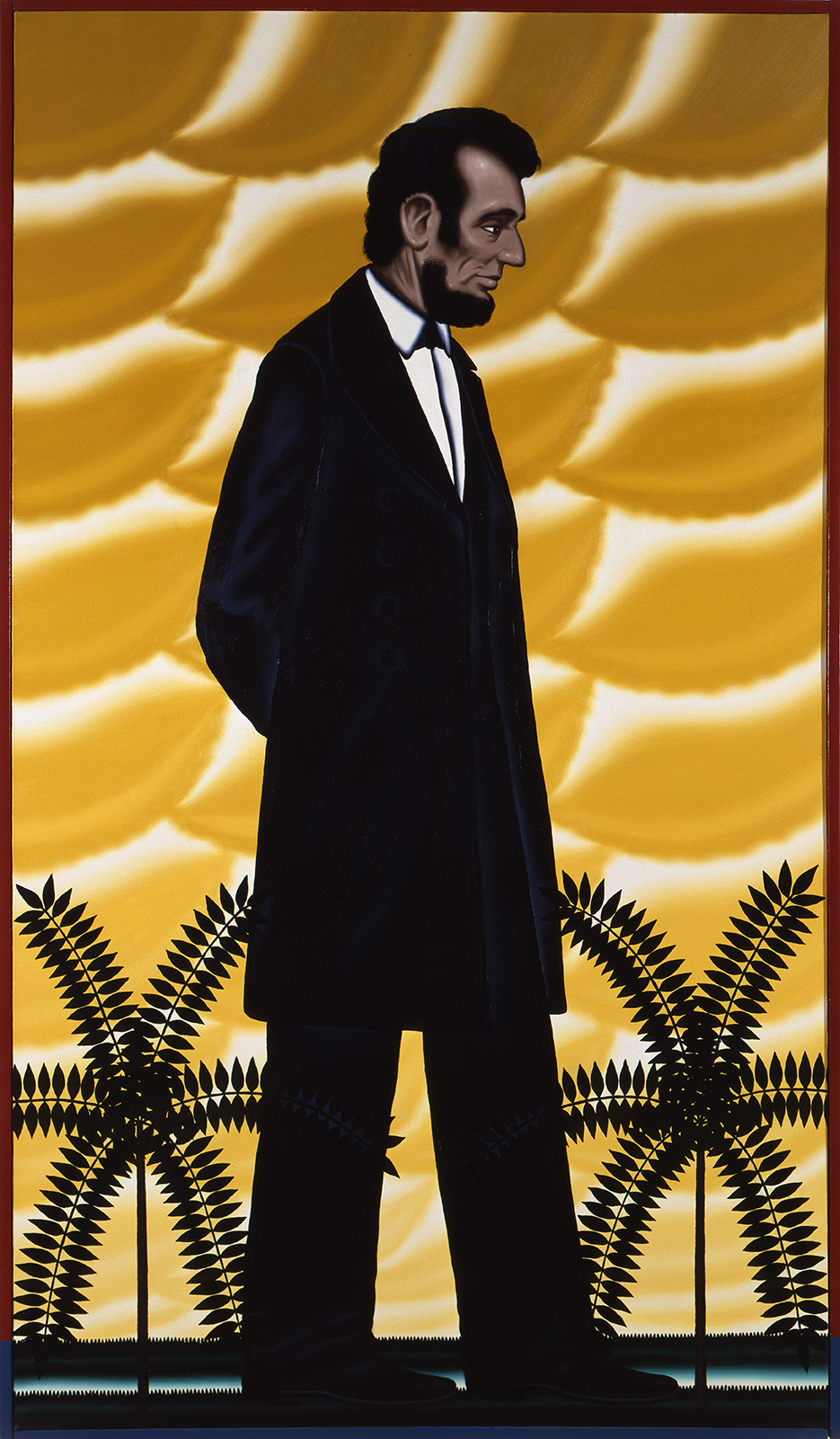

Lost America, 1989, oil on canvas, 85 1/2 x 49 3/4 in., Chicago History Museum

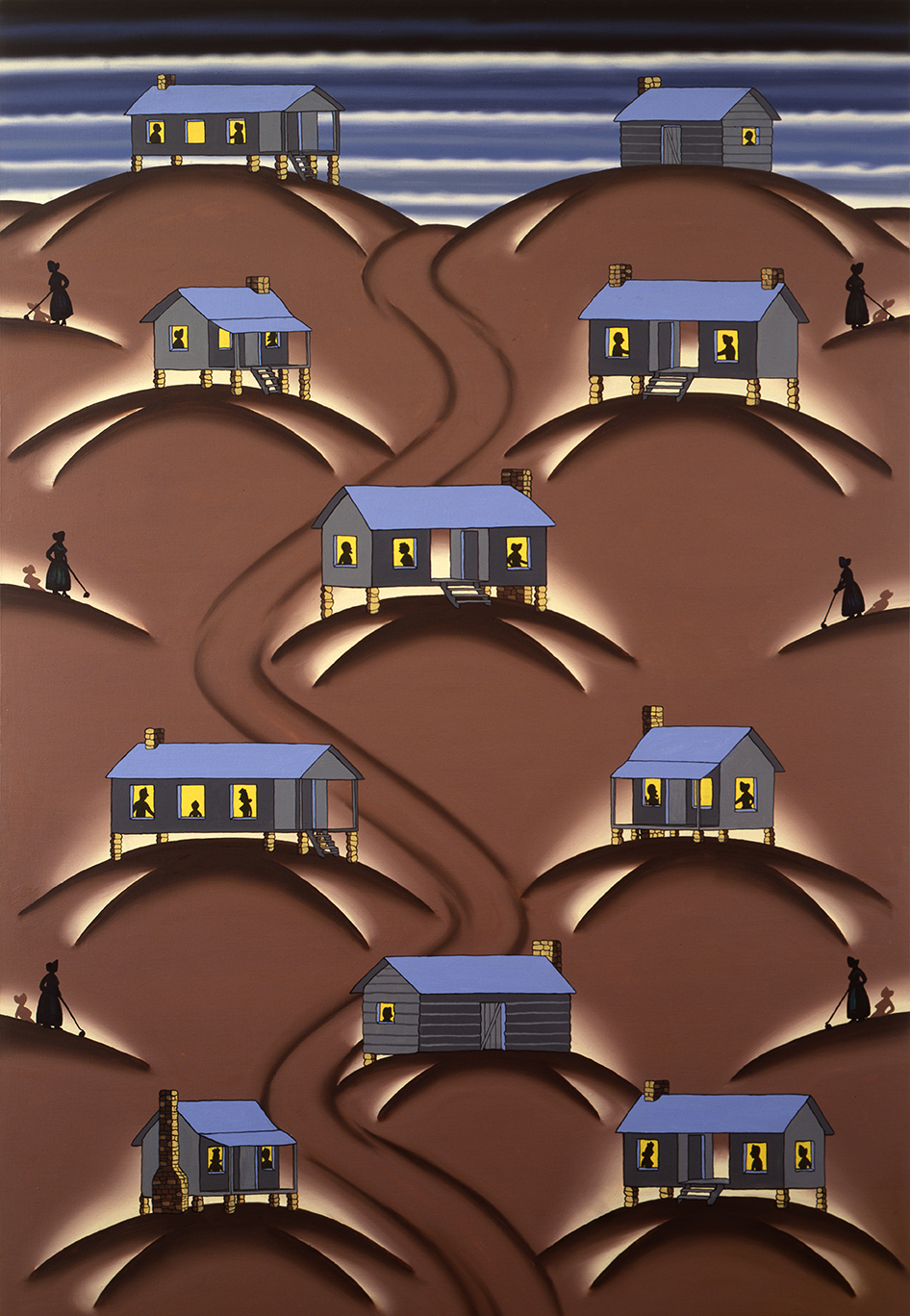

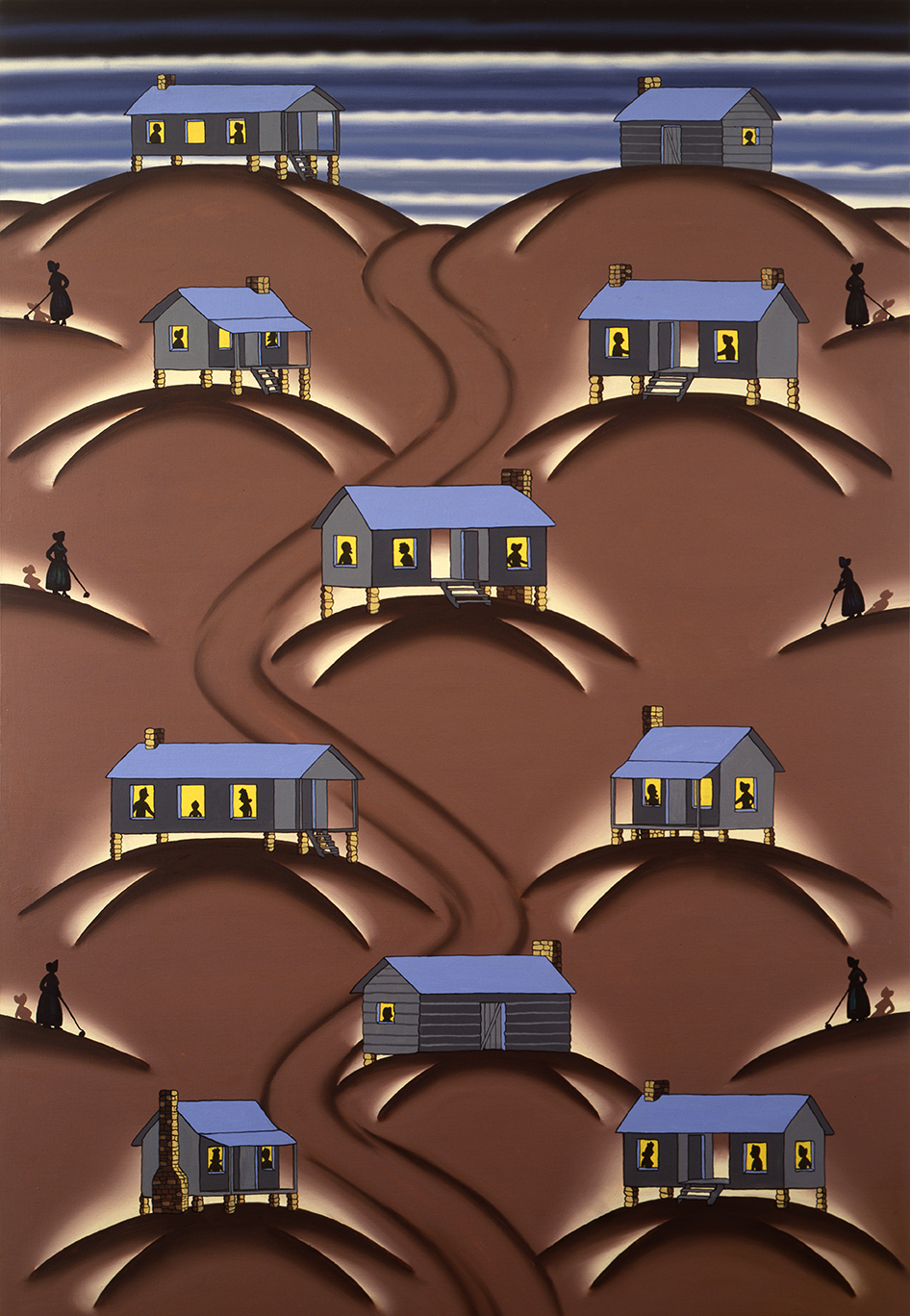

Ancestral Homes of the Type Utilized By My Forefathers: Shotgun; Dog Trot; Slab-End; Log Houses, 1990, oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in.

Twentieth Century Plague: The Victims of AIDS, 1995, Italian glass mosaic, 10 x 14 feet. Installed in the lobby of the Foley Square Federal Center in lower Manhattan. Brown’s statement:

On this ancient cemetery site below the modern skyline of New York City a contemporary tapestry of human faces, each made thin and hollow by the ravages of AIDS, descends like some medieval nightmare into a mosaic of death heads in memory of those of all races who have suffered and died too soon.

Virtual Still Life#15: Waterfalls and Pitchers, 1995, oil on canvas, painted wood, ceramic vessels, 37 1/2 x 50 x 9 in. Flint Institute of Arts. For Nicholas Lowe.

Calif. U.S.A. With Astonished Couple, 1996, oil on canvas, painted wood, ceramic vessels, 48 x 60 x 12 in. For Linda and Dolores Cathcart.

Bonsai #2, Climbing with the Cascade (Kengai), 1997, oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in. Roger Brown Estate and Kavi Gupta.

Untitled (garden arch, shadow falling) 3rd to last sketch in Roger Brown’s last sketchbook, drawn in from 1993 – 1997. Roger Brown Study Collection Archive.

Roger didn’t teach much (formally) during his life, but he’s been teaching robustly, posthumously, for the last 20 years. We are eternally grateful for Roger’s gifts to the School and the world.

Lisa Stone, 11/22/17

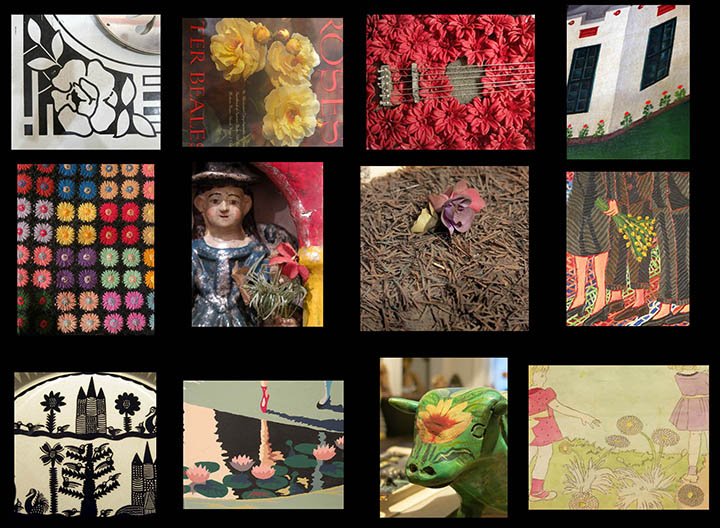

We often refer to the Collection as an ecosystem, an array of individual elements that coalesce into an entity, each part contributing to the limitless possibilities for thinking about, around, and through objects and their relationships. This approach opens the floodgates of possibility, which are currently stuck open.

An analogy we had neglected to consider, that came rushing through the floodgates, is the jigsaw puzzle. Let’s pretend this missive is a dining room table, on which I’ll dump out the box of what’s happened and sort out the pieces into a picture of spring and summer, 2017, at the Roger Brown Study Collection.

Kamau Patton holding puzzle piece

Who came and what they did

classes/guests/exhibitions

In Spring semester class projects put us through our paces and sprung surprises on us right and left. Nick Lowe’s Research Studio 2, ART OBJECTS ALIVE! class began by examining Roger Brown’s written responses to troubling works of art or situations, specifically David Nelson’s Mirth & Girth painting and Dred Scott’s What is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag?, both of which caused uproars at SAIC.

The class then explored the Collection with the directive to find an object or objects that were troubling or troublesome, friction-filled, or angst provoking. They had no difficulty discovering difficulty.

The class then explored the Collection with the directive to find an object or objects that were troubling or troublesome, friction-filled, or angst provoking. They had no difficulty discovering difficulty.

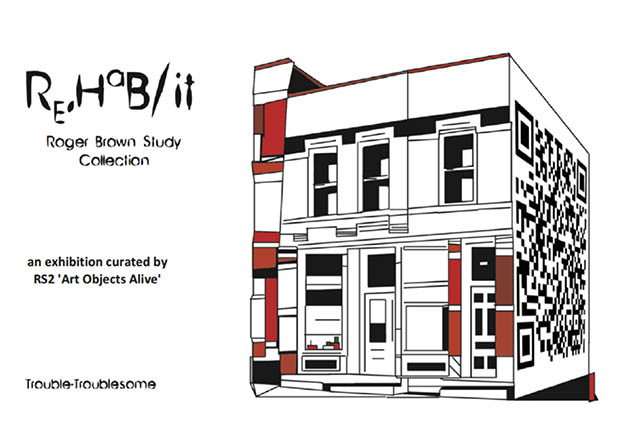

They then re-made the object(s), purposefully reclaiming them from the realm of trouble. They curated the exhibition RE-Hab-it, creating interpretive settings for their objects. The work was sophisticated and inventive, the exhibition expertly curated.

ReHab/It installation

More images can be seen on the ReHab/It facebook page

Kamau Patton’s, Participation and Self-Organization, a class in the Visual Critical Studies Department, met at the collection early in the semester.

Students were instructed to find an area or work of art or concept that inspired them to consider the collection as an ecosystem, a whole of many diverse parts, to consider dimensions of space and time and philosophical interpretations. They returned to the Collection in early May and presented their projects, which once again opened the collection to new and novel ideas and possibilities.

Qais Yahia Assali in his western shirt project

As a parallel project Kamau invited artists Mary Eleanor Wallace and David Sampson to photograph areas of the collection. Mary Eleanor had jigsaw puzzles made of 6 images, which she installed in the areas they depict, as “puzzle stations.”

Puzzle in process

The students and RBSC staff members had a few hours to work on the puzzles, either individually or in groups. We all became completely immersed in the enchanting process of puzzling over many small parts of a picture one could see on the box cover, or in reality, right in front of our eyes. Guests may now schedule time to gaze at an area in the collection, and try to assemble it, piece by piece.

Sculptures by William Dawson coming together in the bedroom puzzle.

Object Puzzles was originally a group exhibition/retail project released in December 2016 at Tusk in Chicago. 20 different artists were asked to make an object that would be photographed and the photo was made into a cardboard jigsaw puzzle. Guests at the opening event were invited to put the puzzles together by referencing the physical object only. Photos taken by David Sampson. Project curated by Mary Eleanor Wallace. We thank them both!

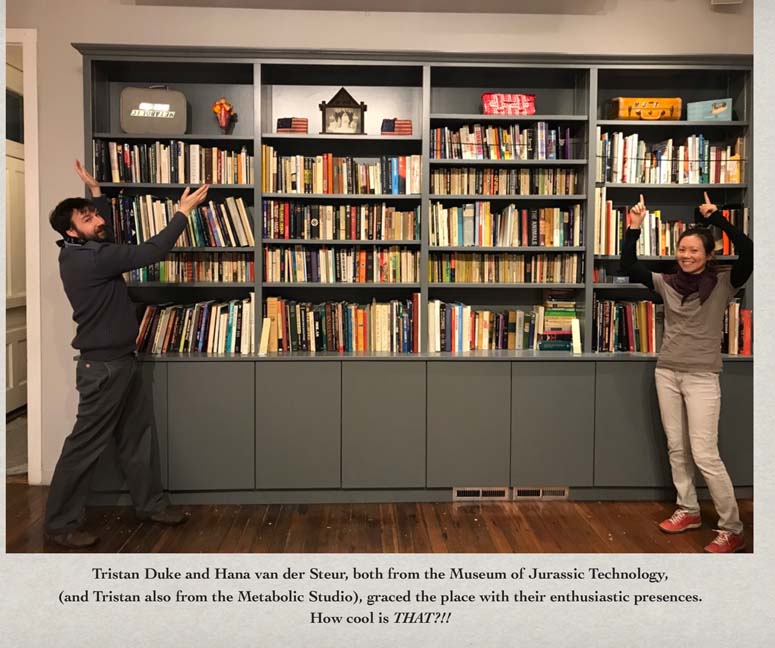

Nick Lowe’s Special Collections Practicum class met for most of the semester at the RBSC. The class got rolling the first day of class, doing condition reports and packing the Doris E. Lane First Ladies dolls for their return trip to the Museum of Jurassic Technology.

Sam Snodgrass and Elizabeth Mescher conditioning First Lady dolls.

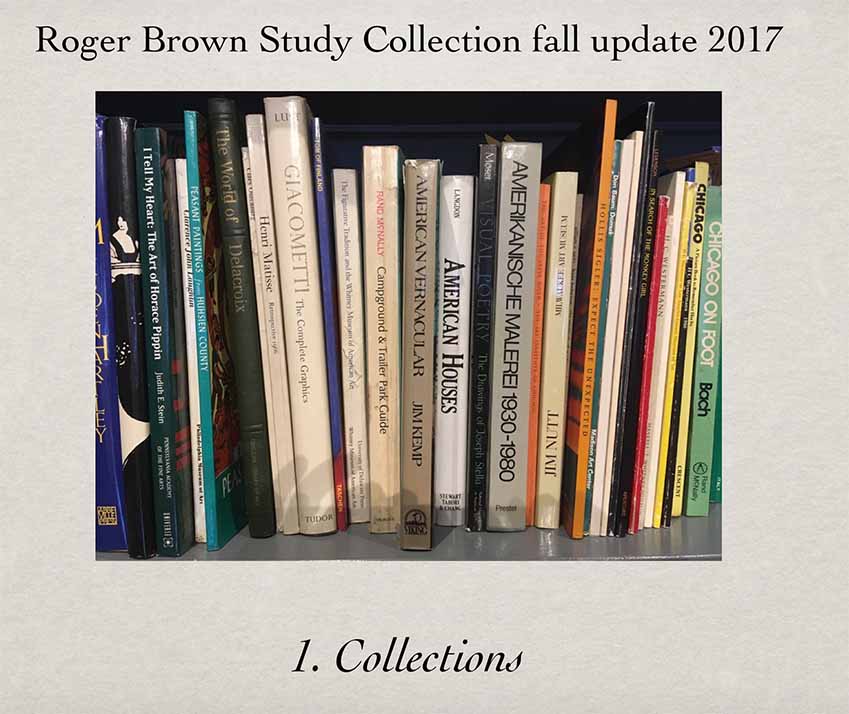

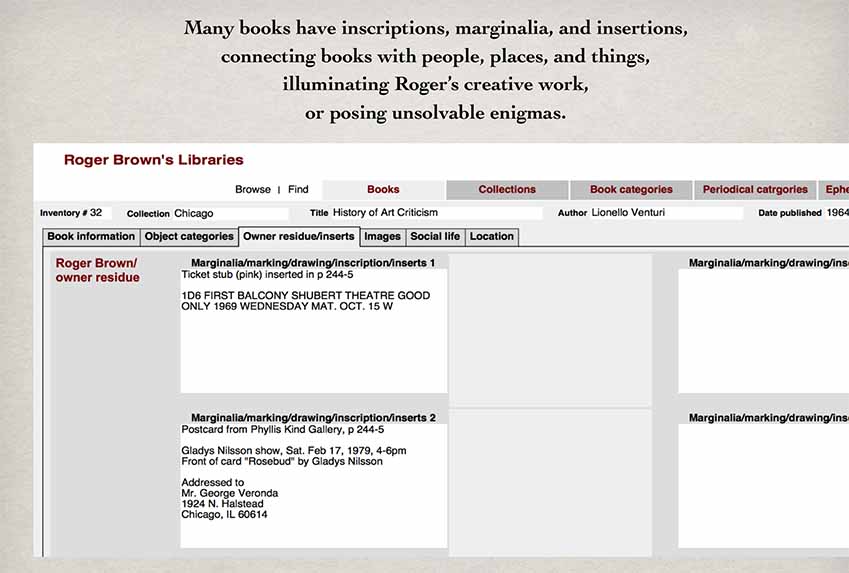

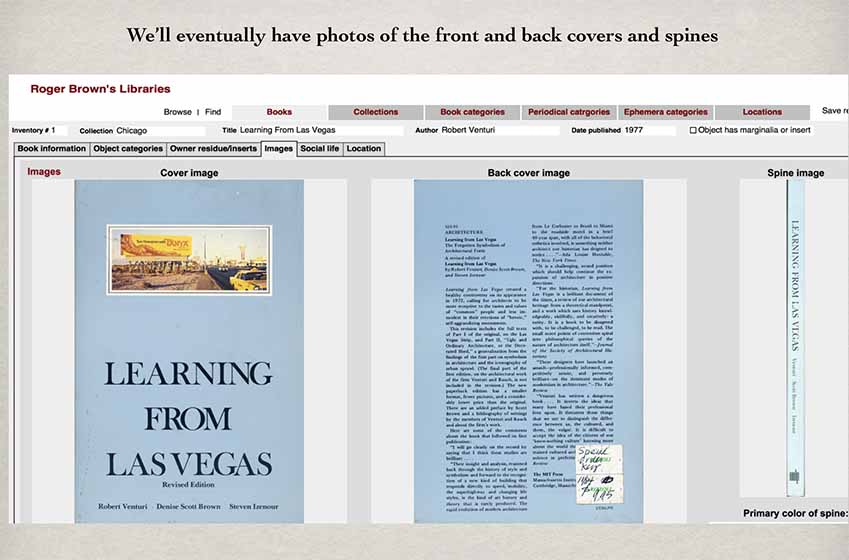

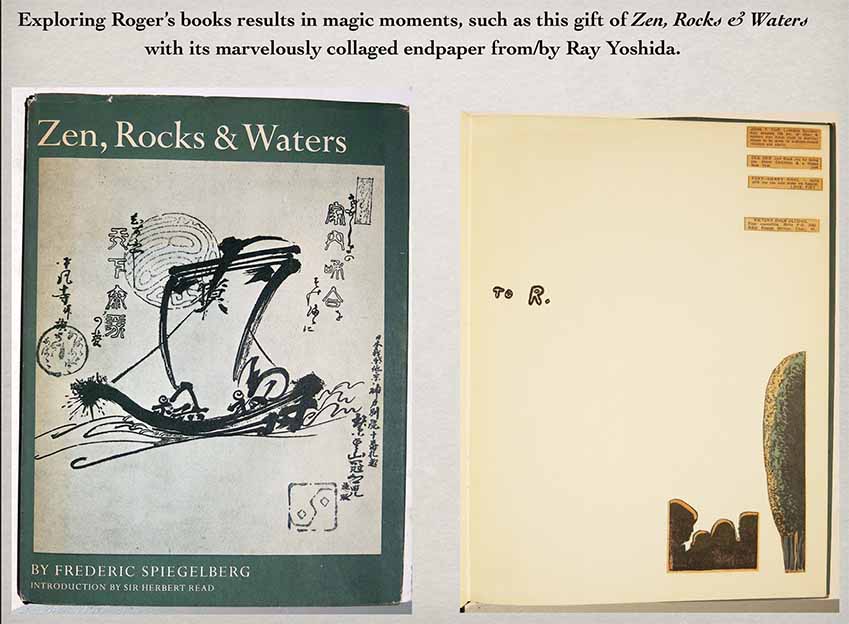

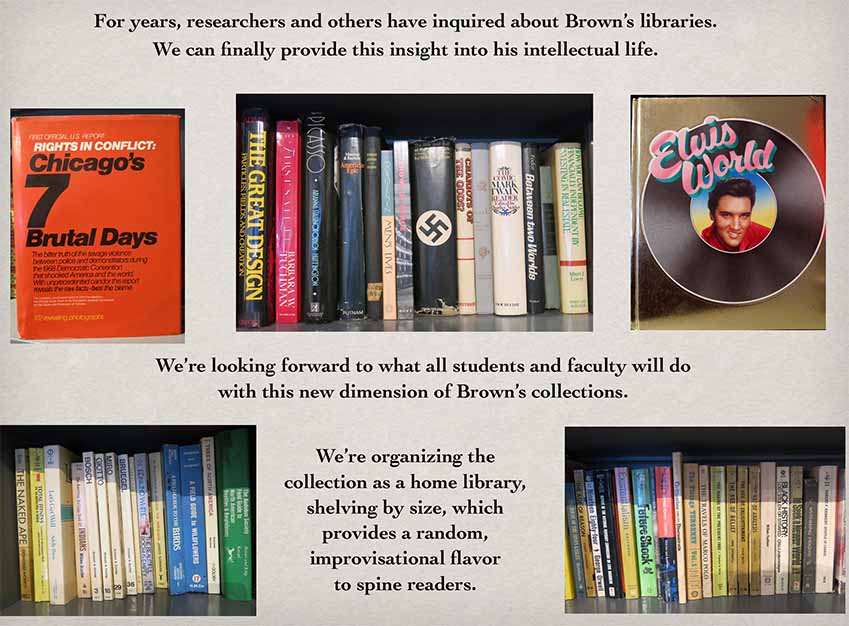

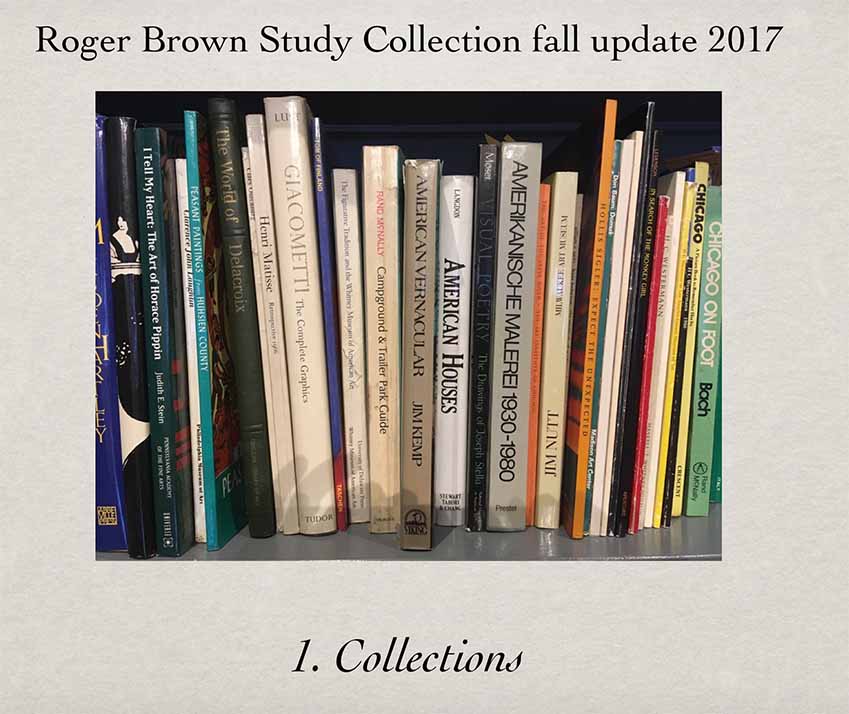

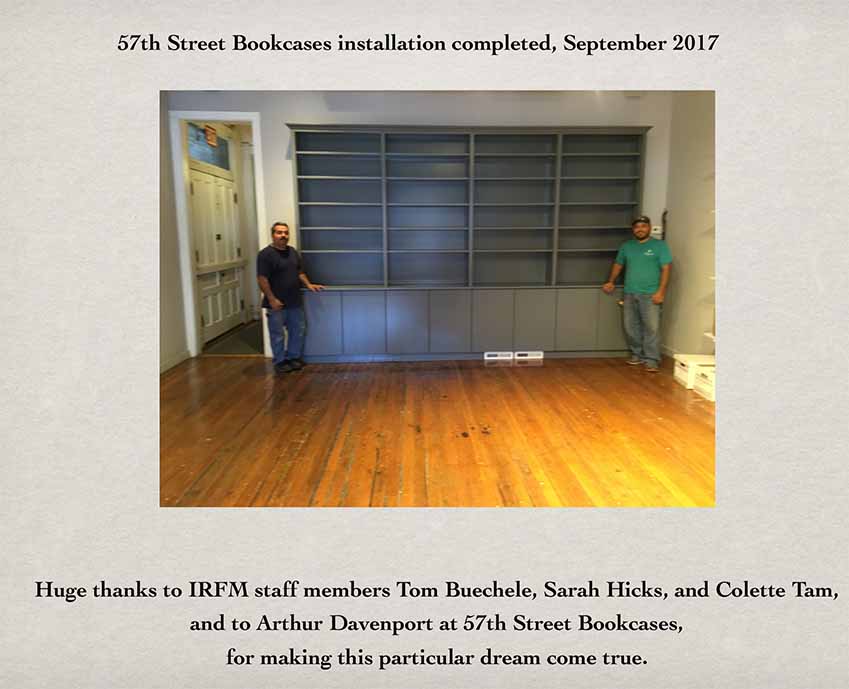

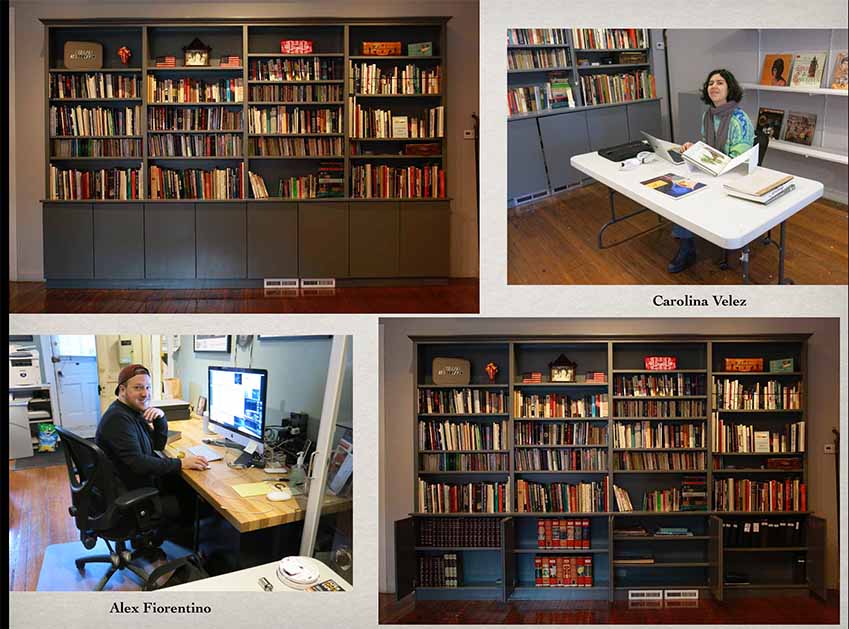

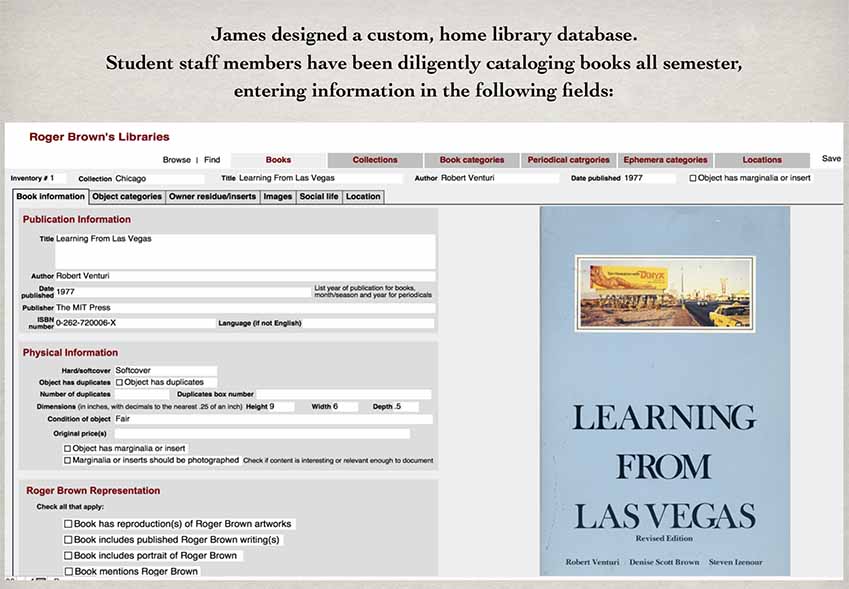

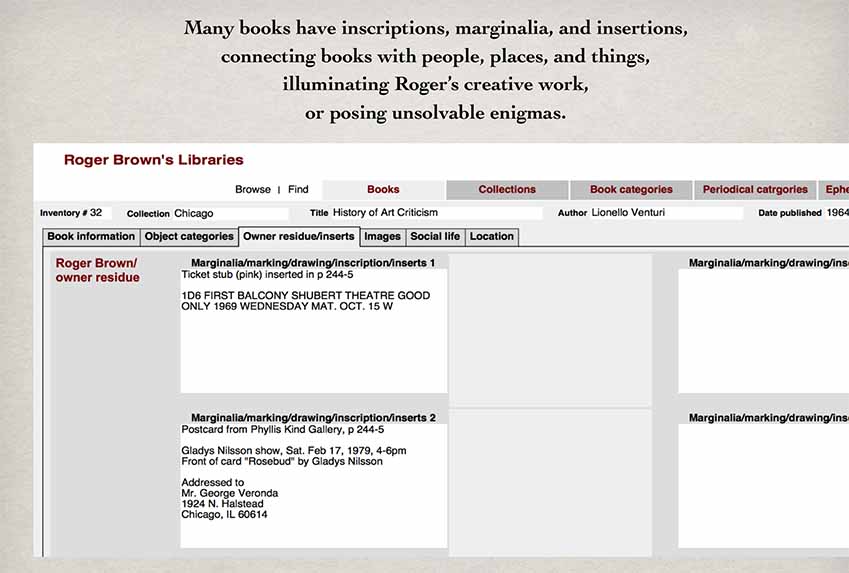

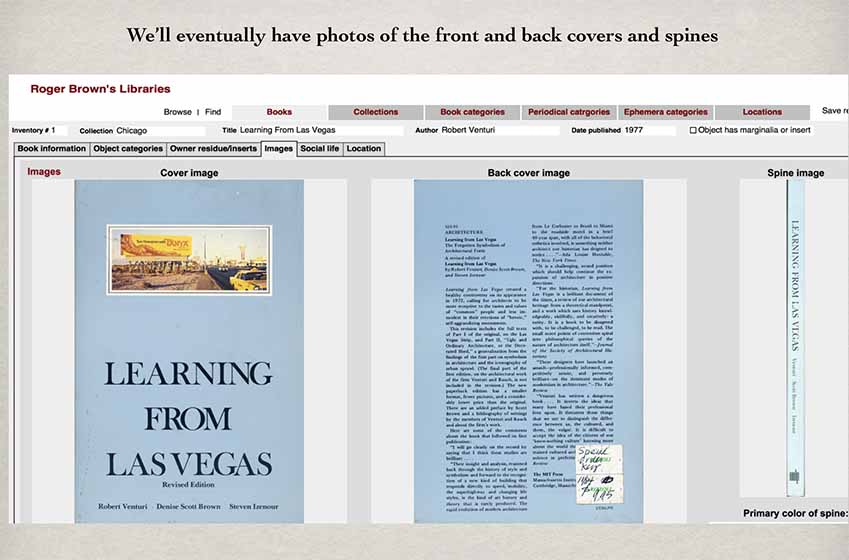

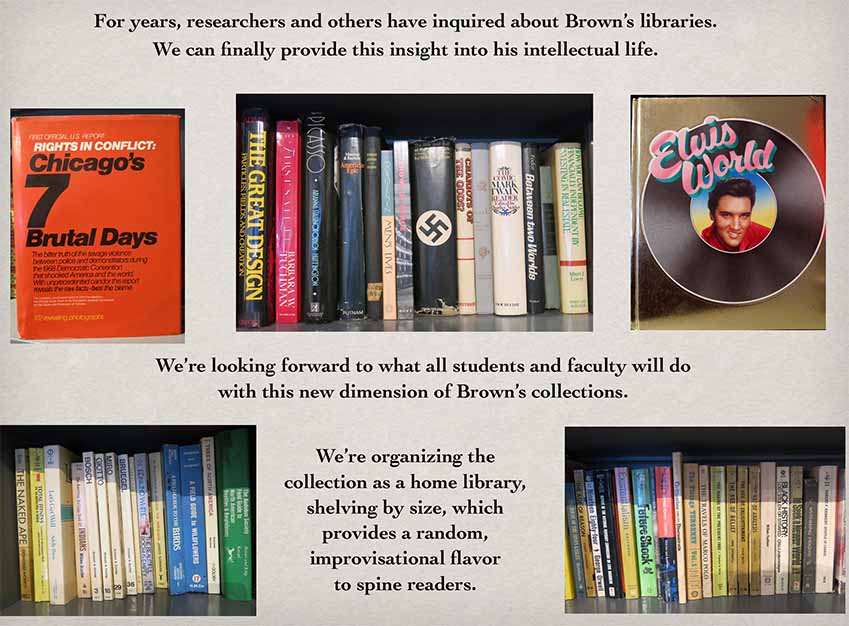

One class team addressed our current plan to create bookcases on the west wall of the orientation/project space, so we can finally unpack, organize, and provide access to Brown’s libraries from all three homes. Emily Fenn, Sam Snodgrass, Kaylie Deng, and Elizabeth Mescher took on the project to consider aspects of this project, including:

- Assessment of the books in terms of size, subject, condition.

- Assessment of ephemeral materials found in the books, as well as Brown’s notes and marginalia.

- Strategies of display: organizing by color, size, subject, completely random.

Elizabeth Mescher, Sam Snodgrass, Kaylie Deng, and Emily Fenn at work.

Bookcases will be installed in early October so watch this space!

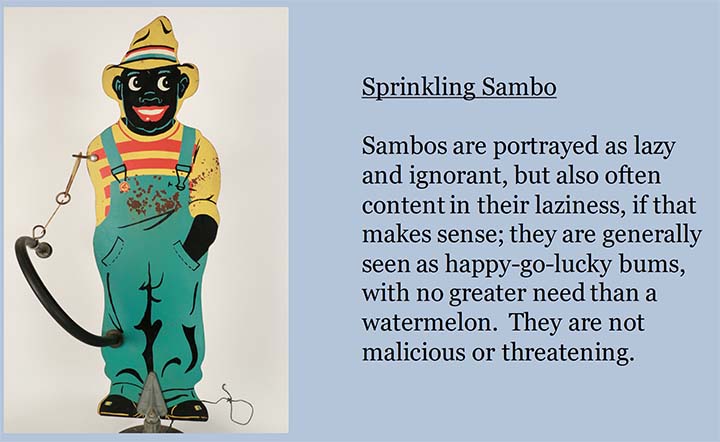

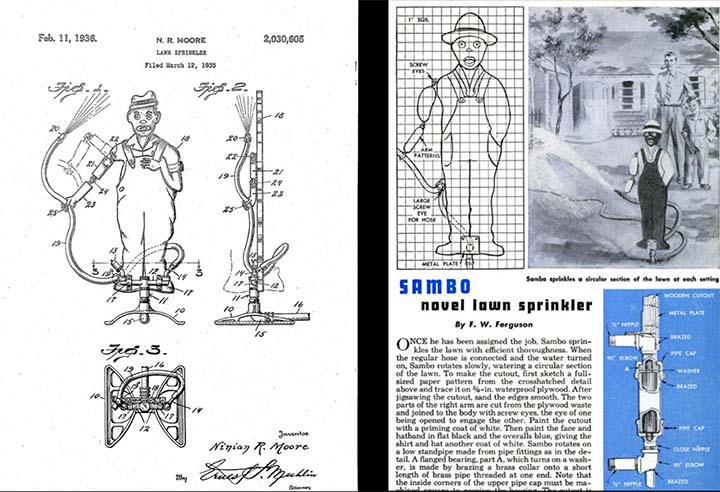

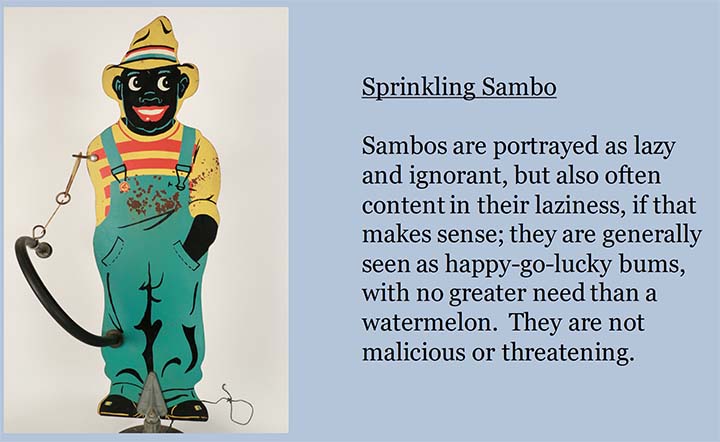

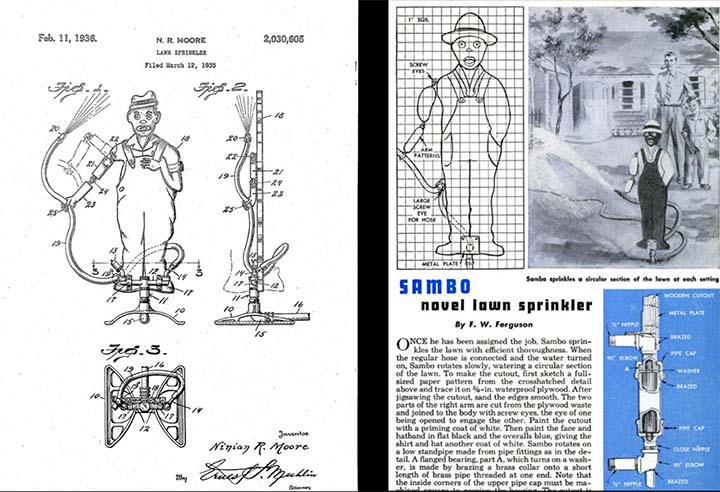

We’re currently engaged in the project to research and contextualize the eight intentionally racist objects in the RBSC, to develop narratives within the interpretation of the larger ecosystem of the collection, a tightrope of presenting objects as historical evidence, providing a critical analysis of what they express, and placing them in historical and cultural contexts without apologizing for their existence in the collection.

“Mammy” doll doorstops

In Nick’s class, Alejandra Vargas examined the objects and conducted research into their manufacture and meanings and the questions they raise.

RBSC staff communicated with Lisa Kemmis, museum assistant at the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University (Michigan), to talk about how to effectively interpret these objects.

The Museum’s founder, David Pilgrim, who is also Ferris State’s vice president for diversity and inclusion, said of the objects he collected and gave to the museum, “Using racist objects as teaching tools seems counterintuitive—and, quite frankly, needlessly risky. Many Americans are already apprehensive discussing race relations, especially in settings where their ideas are challenged. The museum [and this book] exist to help overcome our collective trepidation and reluctance to talk about race.”

Ms. Kemmis provided invaluable information about several racist objects, including Sprinklin’ Sambo, an object represented in the RBSC and the Jim Crow Museum, which Alex explored in her project.

Alejandra Vargas’ report on Sprinkling Sambo

Sprinkling Sambo archival materials provided by the Jim Crow Museum staff

Near the end of the semester we agreed to host an exhibition of works by 18 students in Michael Ryan’s What’s My Job class. The class showed a high level of esprit de corps and pulled together the show, Roger That, in record time.

“Roger That” closing reception

Collections

Faculty member Tim Nickodemus has been working on a many-faceted project around Joseph Yoakum’s work. He made 35 Second Hand Land Scapes that were installed in the Yoakum Room during the annual six-month rest rotation. We were honored to have his creative responses on view this summer. We’ll show them again in the next rest rotation, March 2018.

Tim Nicodemus, Second Hand Land Scapes

Smart staff at the Smart Museum hosted Drawing in the Dark: Landscape, Memory, and the Artist’s Mark with guest artist Tim Nickodemus. Participants first met at the Smart Museum for an evening exploring landscapes and Yoakum works in the Museum’s collection, then drawing and writing Yoakum-inspired postcards. Two weeks later they met at the RBSC. Following an inspired presentation by Tim, participants explored the collection and then hands got dirty and dark drawings were made.

Erik Peterson with blue fingers

Collaborative drawings being made

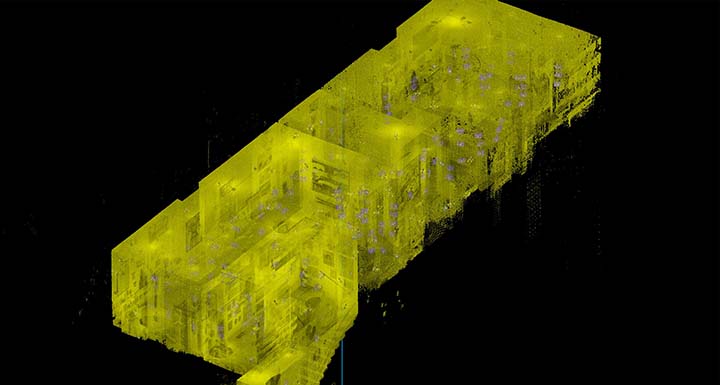

Tim Nickodemus + drawing by 4 artists

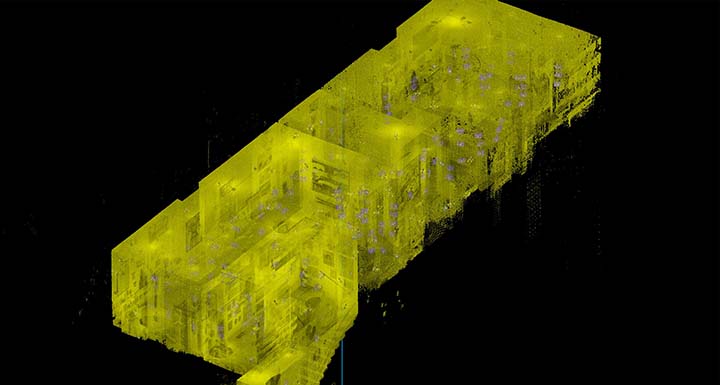

Last summer AIADO faculty member, Jaak Jurisson, taught Virtuality at the Roger Brown Study Collection. Using various 3-d scanners the class scanned architectural spaces and sculptural objects and used the information to manipulate, re-design, re-fashion and re-purpose the spaces. The class began the project, which James Connolly completed, to scan the entire RBSC with a FARO scanner. The files provide invaluable documentation for the eventual renovation of the second floor and two stairways, and give us an unexpected and magical way of seeing in, through, and around this place.

James Connolly, this place magically rendered

Loans

We’ve worked with Kavi Gupta staff to organize loans of works by Roger Brown, Jim Nutt, and Christina Ramberg to the exhibition Famous Artists From Chicago 1965-1975. Curated by Germano Celant, this major show opens at Fondazione Prada/Milan on October 19. Celant visited Chicago on the occasion of EXPO CHICAGO, and explored the RBSC, prior to a panel discussion with Gladys Nilsson, Suellen Rocca, and Lisa Stone, at Navy Pier.

Lisa Stone and German Celant

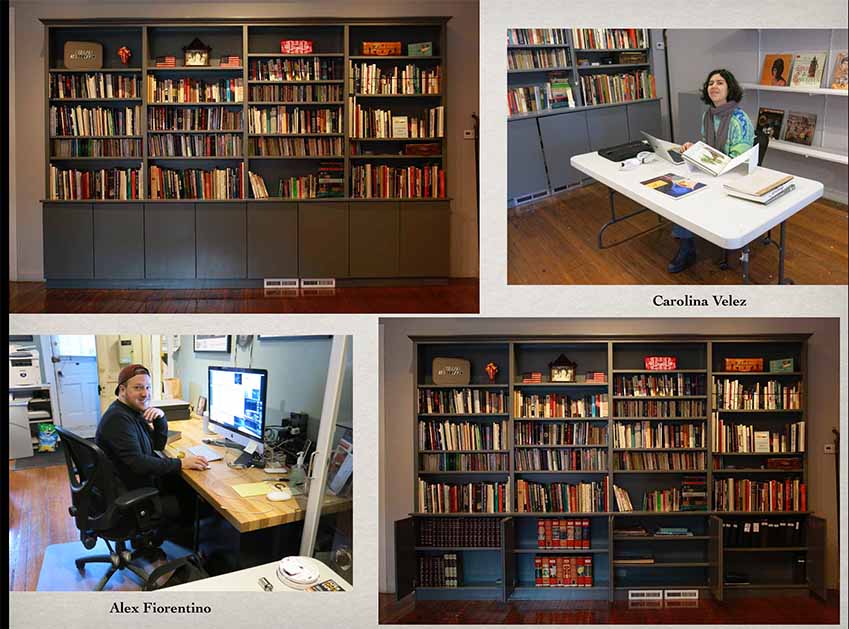

We’re barreling through fall semester with a stellar team of old (Matias Anon, Xiao He) and new (Alessandra Norman, Alex Fiorentino, Cat LaMendola, and Carolina Velez) staff members, with co-curator James Connolly at the helm.

More soon and all the best,

Lisa Stone

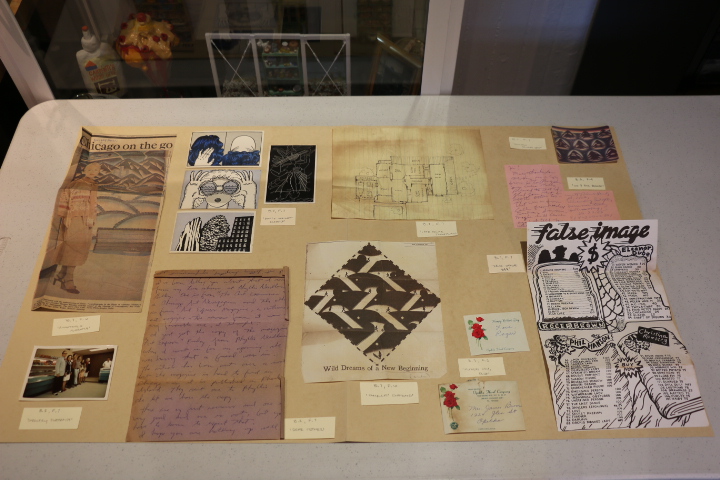

By Gabe Wilson and Lara Schoorl

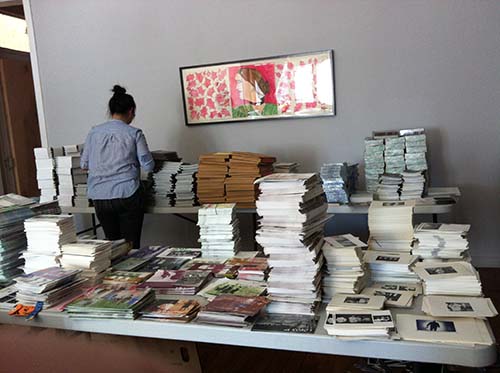

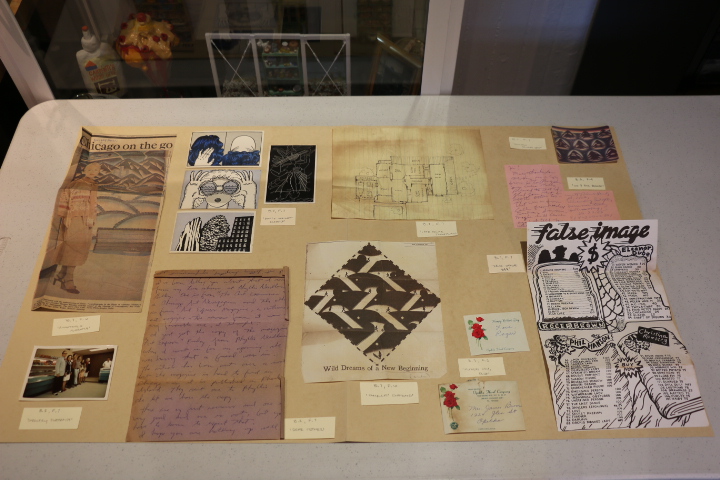

Sometimes it is nice to look without a set purpose. Creating an archive for the first time started like that. We were given three boxes, and then a fourth, with papers and ephemera related to Roger Brown and his family. These documents would become part of the archive of the Roger Brown Study Collection, but first everything had to be sorted: letters, clippings, photos, and ephemera, saved over more than three decades by Greg Brown (Roger’s brother) and his parents. Every piece, when understood in the light of a network of familial, creative, and documentary correspondence, is a testament to the Brown family’s desire to preserve the physical evidence, beyond his works, of Roger’s creative life.

It is strange, the work of archiving, particularly in a house museum. Archiving is an inherently idiosyncratic practice and, perhaps not surprisingly, a deeply intimate experience. In sifting, ordering, and cataloguing the ephemeral traces of a space, place, or person, the wonder of the seemingly mundane quickly captivates and complicates our understanding of history in its most discreet sense.

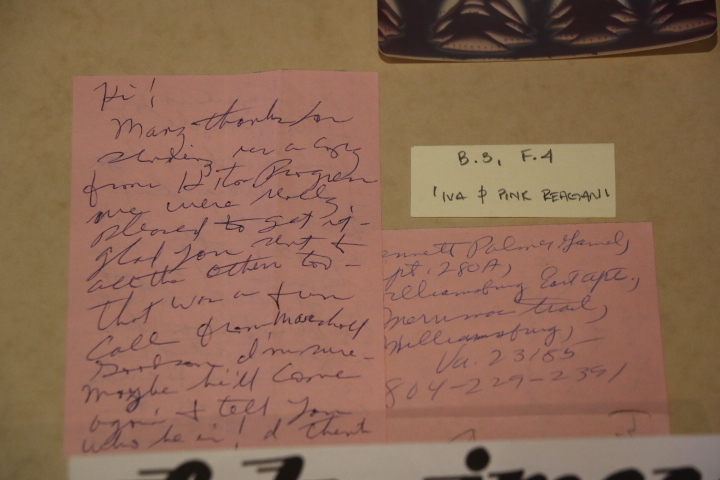

A selection of clippings, letters, photographs, drawings, and exhibition ephemera from the new archival documents shared with the RBSC by Greg Brown. Photo: James Connolly.

When given the task to sort these documents, what does one sort by? This was perhaps the first question to emerge at the outset of this project. Do we sort per person? Per type of document? Do we sort by both? And do we document as we sort, or sort everything first? And when documenting what language does one use? Working on this archive as a team of three people, we had to ensure that there was consistency across all of our contributions. This in a way seems restrictive and bureaucratic, but it also gave us freedom to discover a language of our own. Pink paper was documented as “pink paper;” the color became important. Similarly, large envelopes were named “manila envelopes,” for their color as well and their shape, and regular envelopes became “envelope addressed to.” If the stamps were interesting stamps would be described. Everything that made a document special—that indicated it was that document instead of a similar or the same document but saved by another person—had to be described in such a way that we were able to distinguish two or more similar objects.

Our language became visual and objective, yet remained very particular to our individual perceptions of the materials upon first encountering them. Additionally, questions arose as to what purpose duplicates served. Does it indeed make a difference if there are two of the same documents, but collected by different people? Is it ok to toss a newspaper clipping from 1982? If one clipping contained writing in the margins, it became more valuable than its duplicate, because it was touched more, physically, by one of the lives that is part of this archive. And, should we keep envelopes? Many have Roger Brown’s handwriting on them? These considerations highlighted larger questions around the power of remnant and its ability to express history.

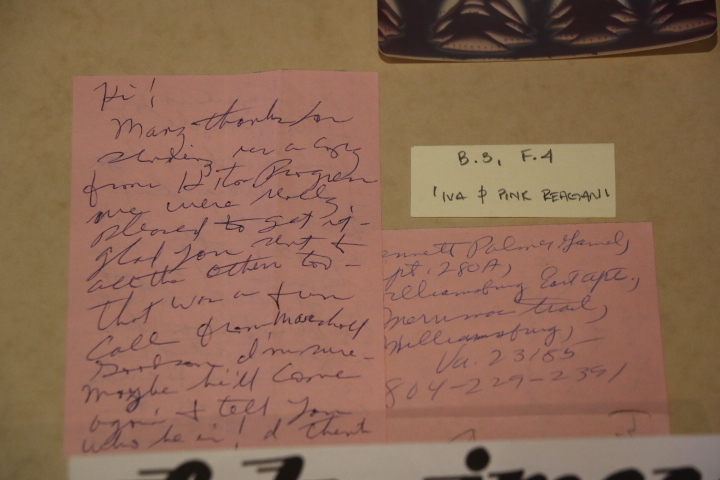

Pink paper notes from Aunt Iva to Elizabeth Brown. Photo: James Connolly.

Pink paper notes from Aunt Iva to Elizabeth Brown. Photo: James Connolly.

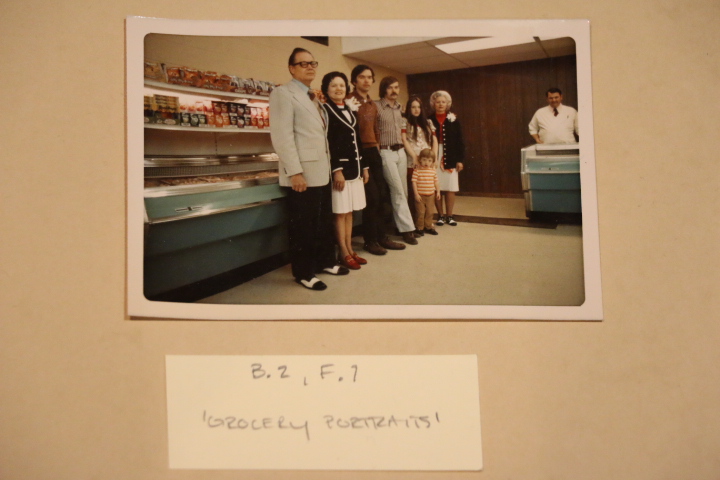

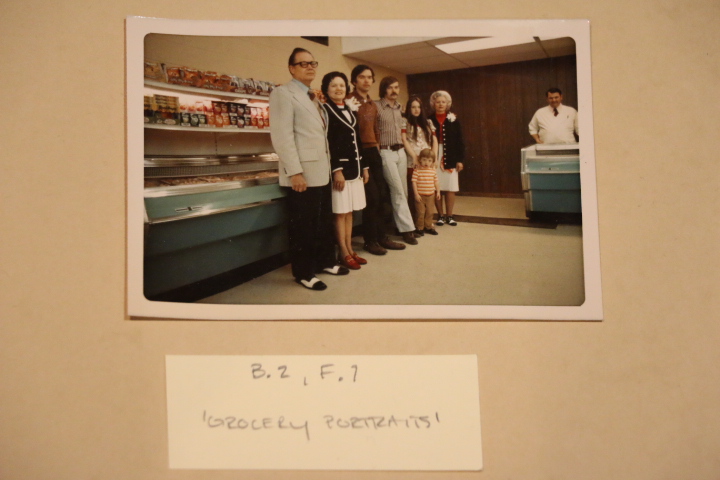

A photograph of the Browns in their family grocery store in Opelika, Alabama. Left to right: James Brown, Sr., Elizabeth Brown, Roger Brown, Greg Brown (others unknown)

A photograph of the Browns in their family grocery store in Opelika, Alabama. Left to right: James Brown, Sr., Elizabeth Brown, Roger Brown, Greg Brown (others unknown)

In many ways, cataloguing the contents of what we called “The Greg Brown Boxes” emerged as a cartographic act. In mapping these materials, orientation was often as important as location. Understanding what a document was necessitated an exploration of how a text or image was situated in relation to a greater material landscape. The import of a photograph of Brown and his family in the their hometown grocery business emerged through a series of letters between Roger, Greg, and their father that illustrated the complicated, sometimes contentious, lifecycle of a family enterprise that was integral to their conception of familial history and whose legacy held different implications for each member involved. Place, particularly homeplace, speaks to a drive in Brown’s work to site his pictorial narratives within a deeply personal landscape.

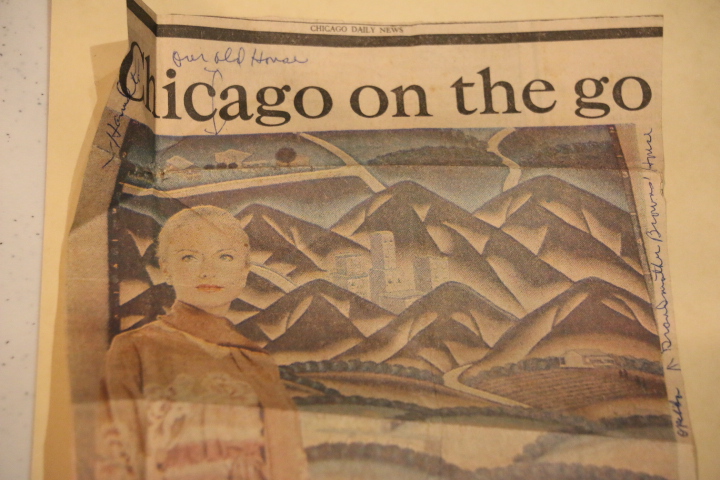

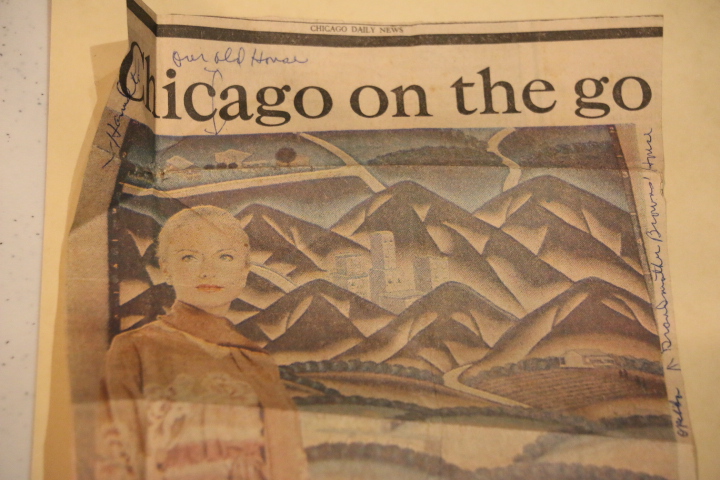

Though occasionally obtuse in his own idiosyncratic methods, Brown often readily addressed specificity in his work through titles and the direct incorporation of text within image. One of his more notable early works, Autobiography in the Shape of Alabama (Mammy’s Door) (1974), speaks directly to a compulsion towards reenacting the known world as something intimately and individually experienced. In a Chicago Daily News article published in the Fall of 1977, Roger’s homage to genealogical history and sentimental landscape became a backdrop for the wife of Chicago’s then mayor and a discussion of an emerging fashion industry in the Windy City. And yet, despite the preservation of many journalistic and critical texts specifically concerned with Roger’s work and exhibition life by the Brown family, this faded society write-up resonates, for me, most eloquently—and in Roger’s own hand. “Our old house”, “Opelika”, “Hamilton”, “Grandmother Brown’s home”; Roger activates the allegorical landscape of his painting with the reality of a deeply intimate history. He translates, for the recipient of this clipping, the very real stakes he took up when portraying home.

Clipping of “Chicago on the Go” by Patricia Shelton from October 4, 1977 edition of Chicago Daily News. Annotations attributed to Roger Brown.

We were looking at lives, and those lives became part of our own lives. Would I have recognized and remembered the tattoos on a guy’s shoulders if I had not fallen in love with Christina Ramberg’s postcard for the False Image exhibition? Or, when a few weeks ago I drove to Iowa City from Chicago with friends we passed a sign on the I-88 that read “Reagan’s Boyhood Home” I knew we were passing Dixon. I knew, because Aunt Iva (who had lived in Dixon) had kept and sent so many flyers that said “Help Preserve Reagan’s Boyhood Home,” because I had read a Chicago Sun-Times clippings from 1980 that proudly wrote about Reagan’s early life in Dixon.

In creating this archive we were given only the limits of the material of the archive. Within those borders three subjective beings started the archive with choosing the first document to be picked up and sorted. And thus, this project literally has formed through our hands. We looked, but were not looking for. We created in a way another life of/for this archive, which apart from its physical presence now also lives as a written and document that will be accessible to whomever comes across it and wants to come across it, and maybe becomes part of more lives.

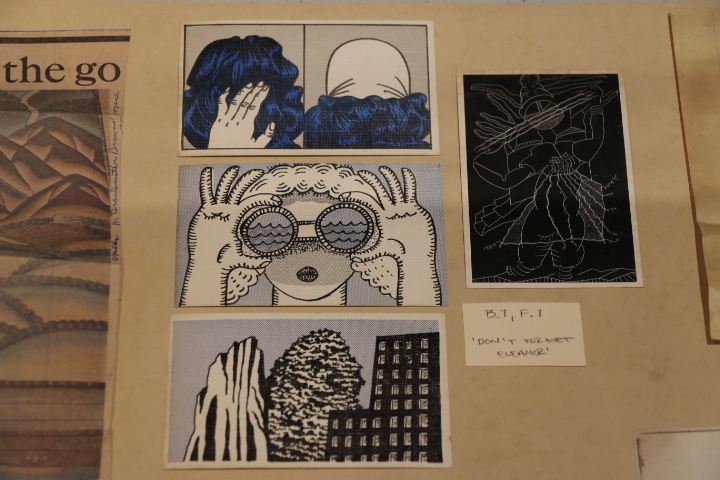

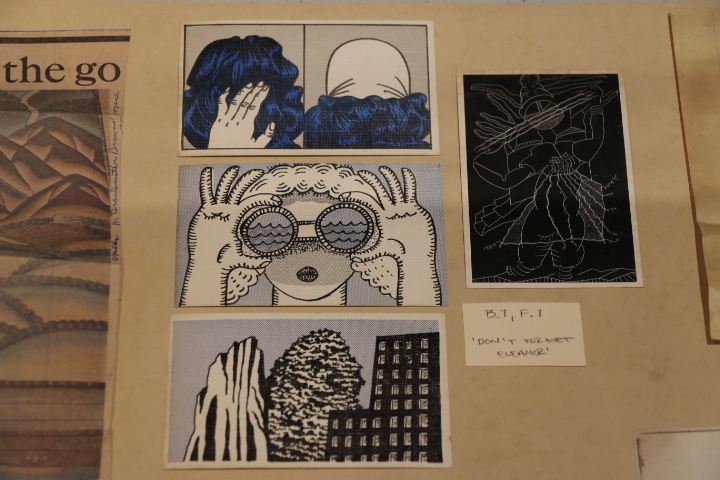

Three promotional postcards for the exhibition False Image from 1968 at the Hyde Park Art Center. (Christina Ramberg, Phil Hanson, Roger Brown and Eleanor Dube)

Gabe Wilson and Lara Schoorl worked on this project as graduate student staff members at the Roger Brown Study Collection. Anna Lenz (MA Art Education ‘15) also worked with them on the project. The Roger Brown Study Collection Archive is open to researchers and the curious by appointment. rbsc@saic.edu

Lara Schoorl is a poet, curator and art historian from the Netherlands and lives in Los Angeles. She holds a BA and an MA, both in Art History from the University of Amsterdam, and is finishing her graduate degree in Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is the publicity manager at The Green Lantern Press in Chicago, and works at the Museum of Jurassic Technology and Hat & Beard Press in Los Angeles. Her recent writing can be found in The Conversant, The Huffington Post, Tique Art Paper, University of Arizona Poetry Center Blog, The Los Angeles Review of Book, and the anthology Sisternhood. She is a co-author of the end of may.

Lara Schoorl is a poet, curator and art historian from the Netherlands and lives in Los Angeles. She holds a BA and an MA, both in Art History from the University of Amsterdam, and is finishing her graduate degree in Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is the publicity manager at The Green Lantern Press in Chicago, and works at the Museum of Jurassic Technology and Hat & Beard Press in Los Angeles. Her recent writing can be found in The Conversant, The Huffington Post, Tique Art Paper, University of Arizona Poetry Center Blog, The Los Angeles Review of Book, and the anthology Sisternhood. She is a co-author of the end of may.

Posted in ALL THE NEWS on Friday, December 23rd, 2016

Lots has happened this year, here at the Roger Brown Study Collections,

which Ben Nicholson elegantly described as a formal garden of inorganics.

Ben’s formal garden analogy is apt for the collection,

which remains arranged as Roger planted it.

In terms of our work here, we’ve been doing a lot of weeding in the back 40…

Here’s what we’ve been up to:

summer

In May and June we closed the orientation/project space to make room for a Special Collections project. Nick Lowe worked with Arts Administration grad student Flora Zhang, on the complete organization of the 32 year archive of the Goat Island performance collaborative.

Flora Zhang processing Goat Island archival materials.

They archived up a storm, resulting in the organization of diverse materials including video and photo documentation, international and national performance communications and ephemera, and costumes and props. The collection was moved to the Flaxman Library and officially became an SAIC Special Collection.

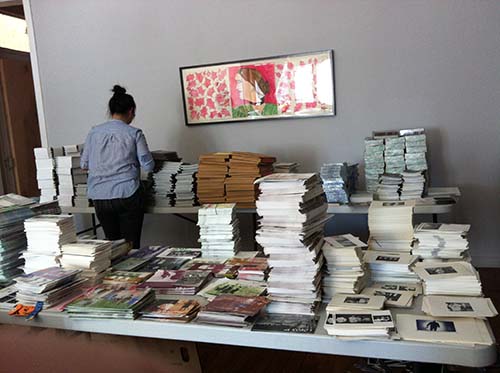

RBSC staff had much-awaited quiet time to work on collections. James Connolly oversaw staff on the ongoing project to advance the Master RBSC collection database, locating and photographing many hundreds of objects and entering info and images.

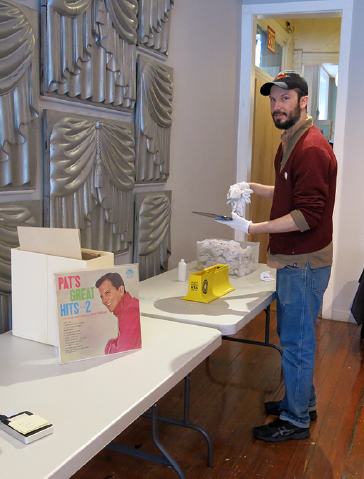

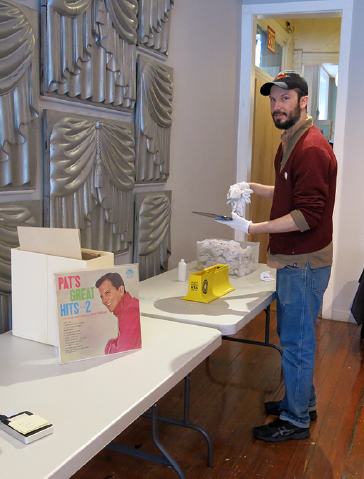

Kurt Peterson cleaning LP albums

Volunteer Kurt Peterson cleaned most of Roger’s ~ 300 vinyl LP record albums, from the 1926, New Buffalo, and La Conchita collections, and began the digitization process. Staff member Matias Anon spent the summer digitizing all the albums.

We mounted a selection of “staff picks” on the Yoshida shelves this fall. Each class that visited selected 2-3 albums for their playlist while in the collection. The albums were played upstairs through the Sonos speakers. We kept track of all album selections throughout the semester. Nina Simone and Johnny Cash are definitely trending!

RBSC “staff picks” record albums––a fine and eclectic selection.

1926, the building

The project to restore the doors, windows, transoms, and install new, wood-framed, uv filtering storms on all windows was completed this fall.

Interior hall doors, fully restored by Restoric, LLC

As more and more buildings in the neighborhood are demolished and the streetscape evolves, 1926 continues to connect the past with the future. At 1926 the histories of the 19th century building and a 20th century artist are performing fully into the 21st century. We’re committed, as always, to enacting historic preservation as a creative activity.

Detail, exterior doors fully restored by Restoric, LLC

The plan to remove the crumbling wood ramp and renovate the sidewalk, and east and west doors, for improved, ADA compliant access was scheduled for 2017. Major construction on the property next door accelerated this project. The new sidewalk and ramp is a major improvement.

left: gangway sidewalk + ramp before. right: new gangway sidewalk + ramp

A security camera and accessible doorbell were installed.

Big Brother’s watching…

Sincerest thanks to the Walter and Karla Goldschmidt Foundation

for their generous support of these projects!

As always, huge thanks to SAIC’s Instructional Resources Facilities Management team,

Tom Buechele, Ron Kirkpatrick, Mike Plummer, Colette Tam, and Rachel Krcmarich,

for their ongoing care of 1926. Speaking of which,

We got I-T done!

All electronic communications and security systems were completely upgraded at 1926. The project vastly improved our internet connectivity, for RBSC staff and all the classes that use it. Thanks to Kevin Lint, Brian Werle, and Jeff Panall for making this happen.

Good House-Museum Keeping

Garage: cleaned and rat proofed!

Bathroom shower: Had been an “archive” space for years, with wire shelves and archival textiles stored there. All were removed and it’s back to being a bathroom shower, to our great relief.

Archive

We struggle to keep ahead of researchers’ queries and requests, but the archive has the knack for keeping ahead of us. We got serious in late November and relocated a van-load of materials that we don’t need regular access to, to offsite storage, freeing up our heads and much needed space.

All unprocessed materials were identified and prioritized for processing. Gabe, Flora, and Xin are all working on processing archival materials, adding descriptions to our finding aid, filing and/or re-housing them.

The Chicago Area Archives consortium held its second annual Chicago Open Archives event in October. We opened the RBSC for tours and put out a spread of very excellent ephemera.

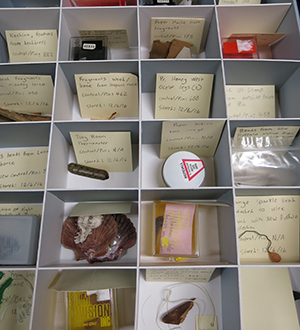

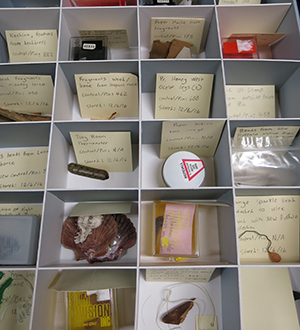

The RBSC St. Honey West Fragment Hospital

For years lost limbs, detached fragments, broken pieces, and bits + bobs were cataloged and stored in the St. Honey West RBSC Archive Hospital – named (by former student staff member Lisa Abbatomarco) after the vampy 1966-67 TV show. Roger acquired two Honey West accessory cards, which can be seen, if you’re on your hands and knees, in the Yoakum Room curio cabinet. The hospital was located in an old bankers box; the wards were overcrowded and, well, inhospitable.

Left: the real Honey West. Right: the old St. Honey West Hospital, and Honey West memorabilia in the RBSC.

Hospital expansion project

We demolished the old hospital to make room for a new 5 story, archivally sound Fragment Hospital.

New archival boxes for object fragments.

Roger Brown’s Sketchbooks!

We worked with Flaxman Digital Librarian Chris Day and his stellar staff, who completed the project to make the digitized versions of all (22) of Roger Brown’s sketchbooks accessible online. The sketchbooks reveal the origin and development of Brown’s creative process, providing insight into his ideas, from his student years to his final works. Enjoy this trove of stunning drawings, invaluable in the interpretation of the resulting artworks, as well as revealing ideas that never went further than a sketch. You can access them here: Roger Brown’s sketchbooks.

Page in Brown’s 1968-1970 sketchbook

Programming: who came and what they did

We hosted approximately 1900 guests this year, with 86 SAIC class visits, 54 in fall semester. Following are views of some highlights from the autumn onslaught of SAIC students, faculty, and other august guests.

Jeremy Biles’ Contemporary Practices Surrealism Seminar

Tim Nickodemus’ Research Studio students making paper museums

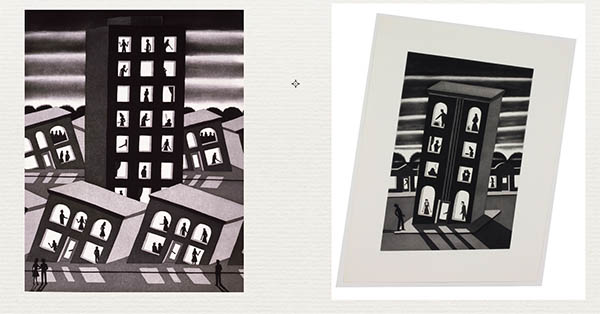

Tim Nickodemus’ students’ museum based on Roger Brown’s Gothic Stadium

Nick Lowe’s class hard at work.

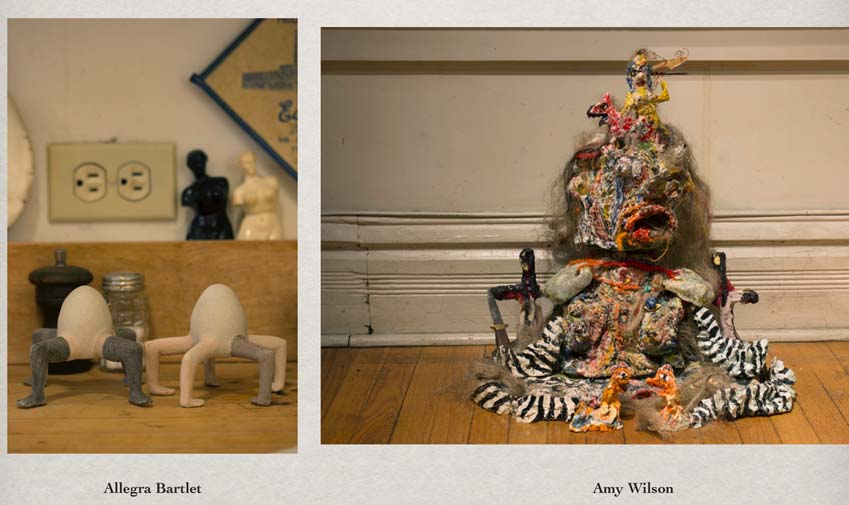

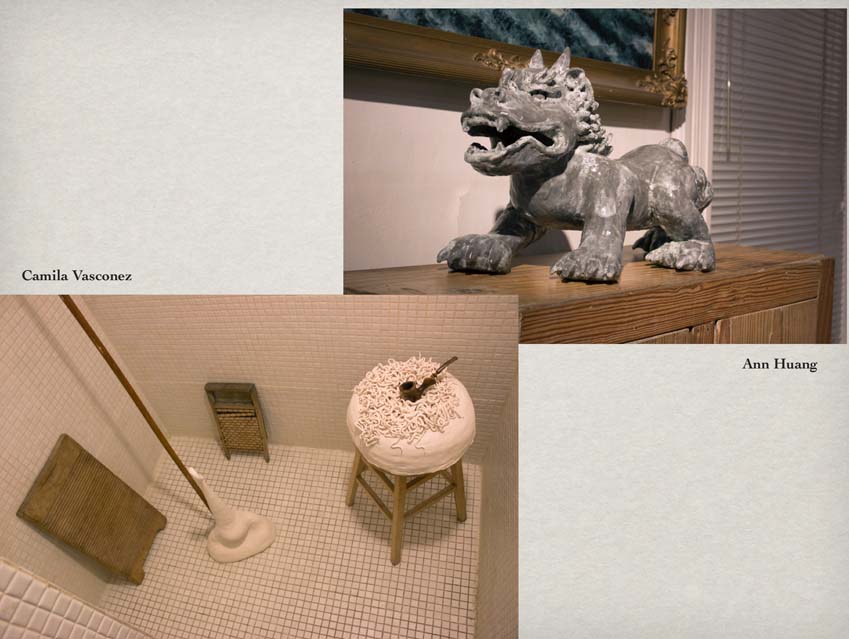

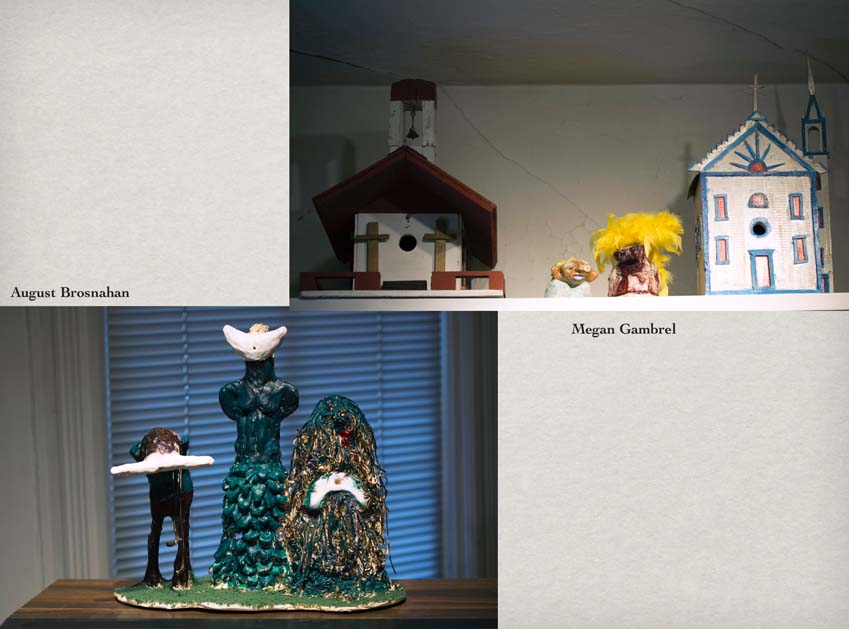

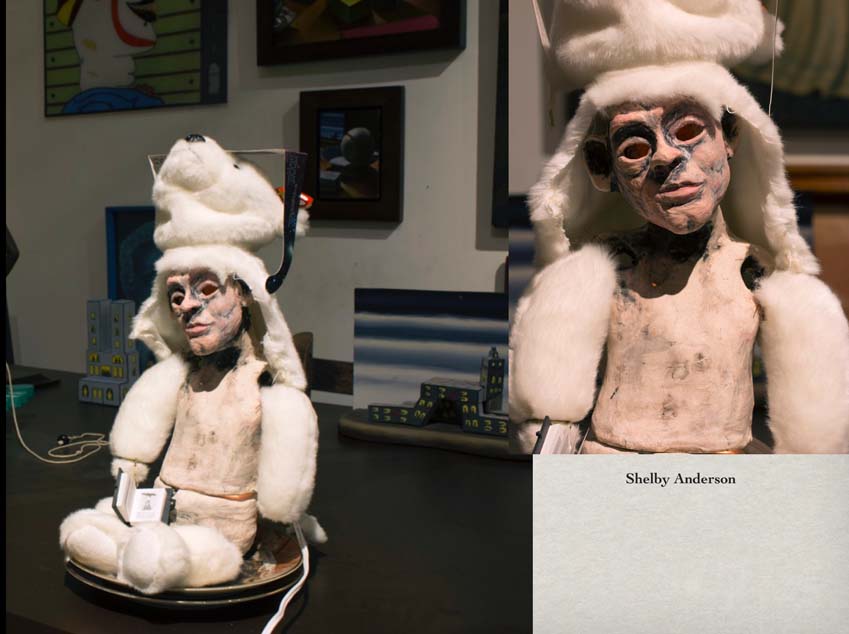

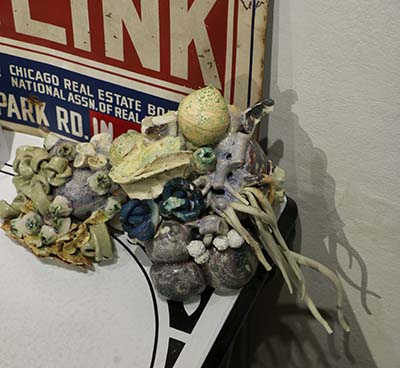

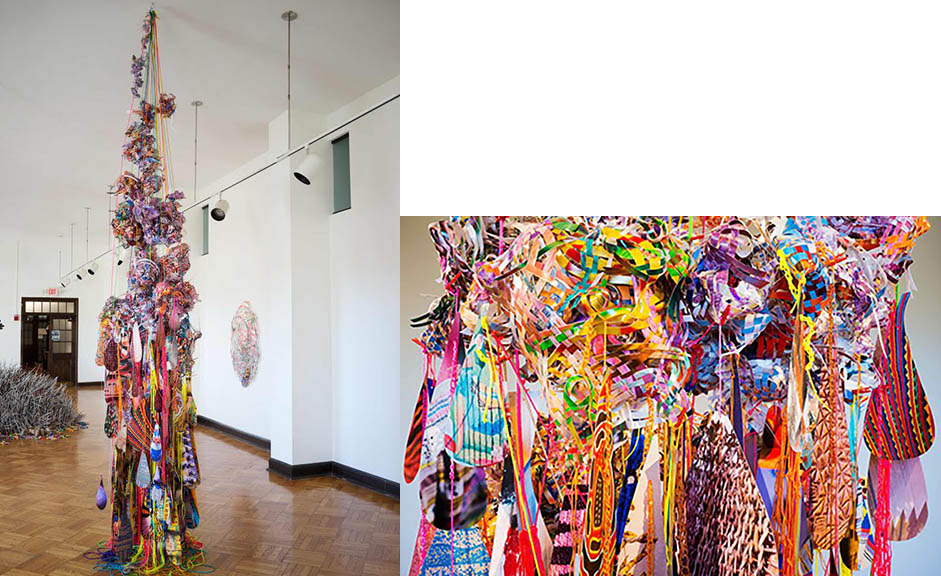

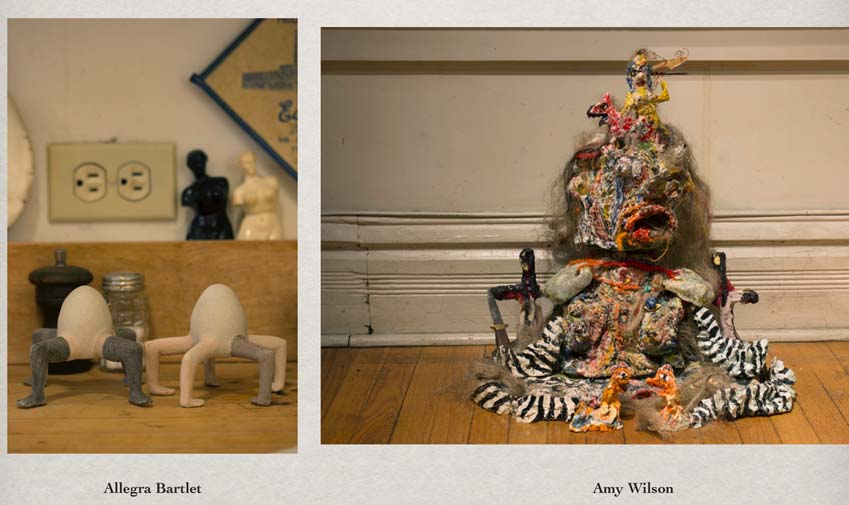

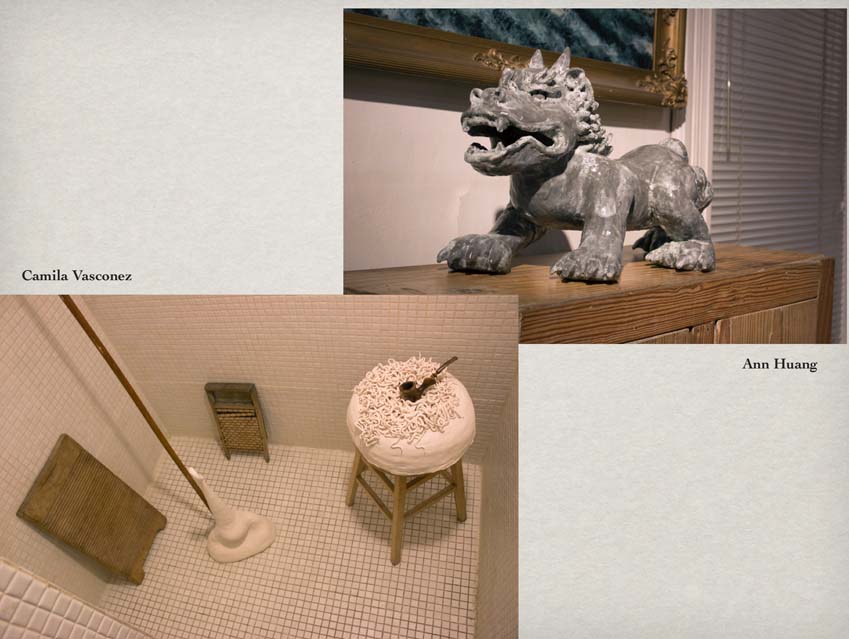

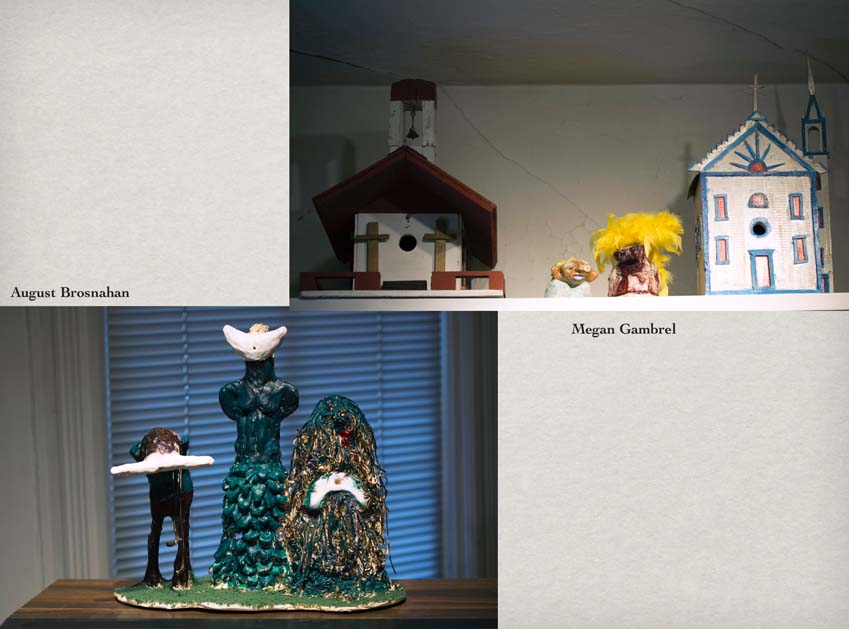

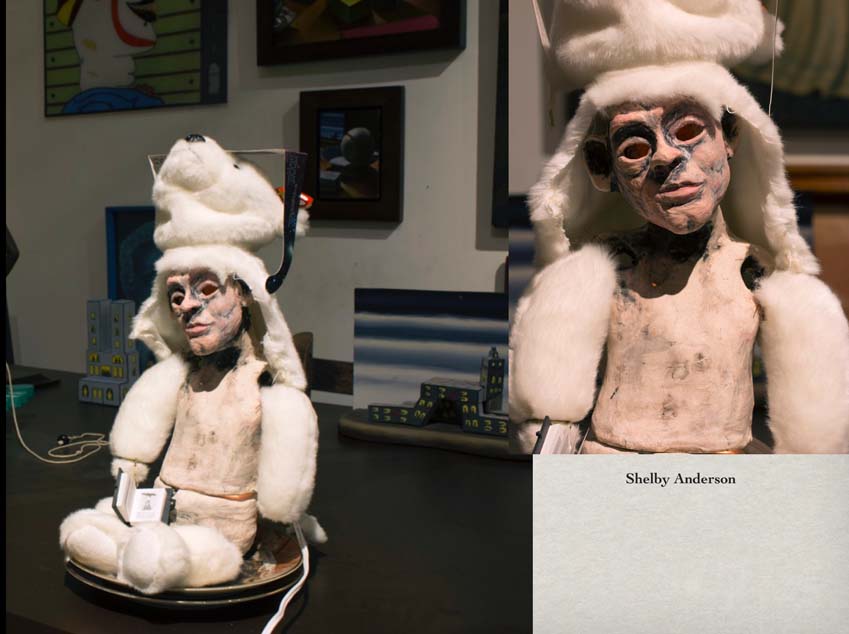

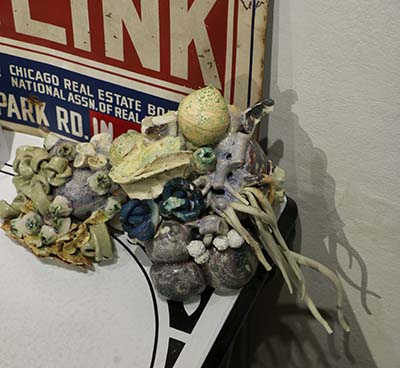

Each fall Ceramics professor Patricia Rieger brings her Curious, Intimate Objects class to explore the collection and connect with a place and/or objects within. The students then make works based on this research and install them throughout the collection and property, for an all day critique. Following are a few examples of many wondrous responses to our formal garden of inorganics.

Kevin Weeder

Victoria Vanderpool

Phoebe Chin

Tabitha Link

Keenan Cook

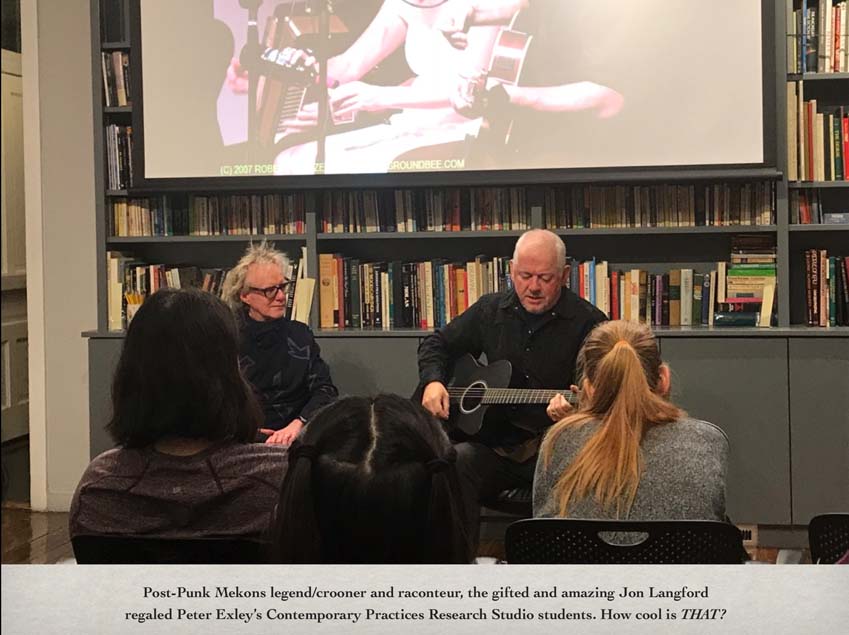

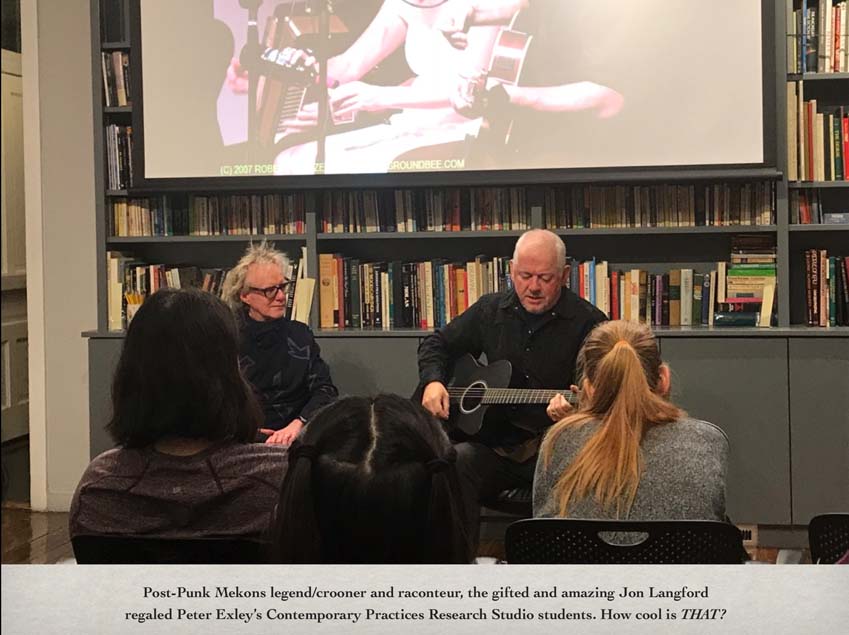

Legendary artist/musician Jon Langford serenaded Peter Exley’s Research Studio students with Mekons’ hit White Riot.

Artist Gary Panter observing

Exhibitions

We extend sincerest thanks for the enormous amount of energy, acuity, creativity, rigor, and resources that the Kavi Gupta team poured into the fall exhibition, Roger Brown & Andy Warhol: Politics, Rhetoric, Pop! The show was insightfully curated and interpreted, and augmented by three panel discussions with an outstanding roster of artists, scholars, critics, and curators, including John Yau, Lisa Wainwright, Dan Nadel, Katherine Andrews, Greg Brown, Russell Bowman, Chloe Pelletier, Jonathan Odden, Will Simmons, and David Getsy. The second floor gallery included five arrangements from Brown’s La Conchita, California home, examples of Brown’s object paintings, and a selection of catalogs, exploring Brown’s and Warhol’s collecting proclivities. The project went far to present Brown’s work in a previously unexplored context and we applaud their efforts to widen perceptions of Brown’s work.

Arrangements from Roger Brown’s La Conchita, CA home

ArtAIDSAmerica

We are honored that that two paintings from the Roger Brown estate are included in the Chicago exhibition of ArtAIDSAmerica. Organized by the Tacoma Art Museum, the show was expanded to include several Chicago artists and is on view in a space created specifically for the exhibition by the Alphawood Foundation, under the direction of Anthony Hirschel. We extend congratulations and thanks to Tony and Alphawood staff.The exhibition is deeply moving, not to be missed. ArtAIDSAmerica, Alphawood Gallery, 2401 North Halsted St., December 1, 2016 through April 2, 2017.

Roger Brown’s Peach Light (1983)

Ladies, First

We went politically, historically, conceptually, and most fashionably correct at 1926 this fall. We were elated to unveil the modest exhibition, Doris E. Lane – Ladies, First –– a collection of dolls bedecked in the most exquisitely crocheted gowns, representing the First Ladies in their inaugural garb (plus the Tricia Nixon Wedding Party), lovingly made by Doris E. Lane.

We know little about Ms. Lane other than she was in fashion design in the Bay area and in the 1960s she began crocheting doll garments––eventually completing over 300––representing a broad range of nationalities and types of garments. She was in her mid 80s in 2010 (or thereabouts), when she donated her whole collection to the Oakland Museum of California, to be sold individually at the Museum’s White Elephant benefit sale.

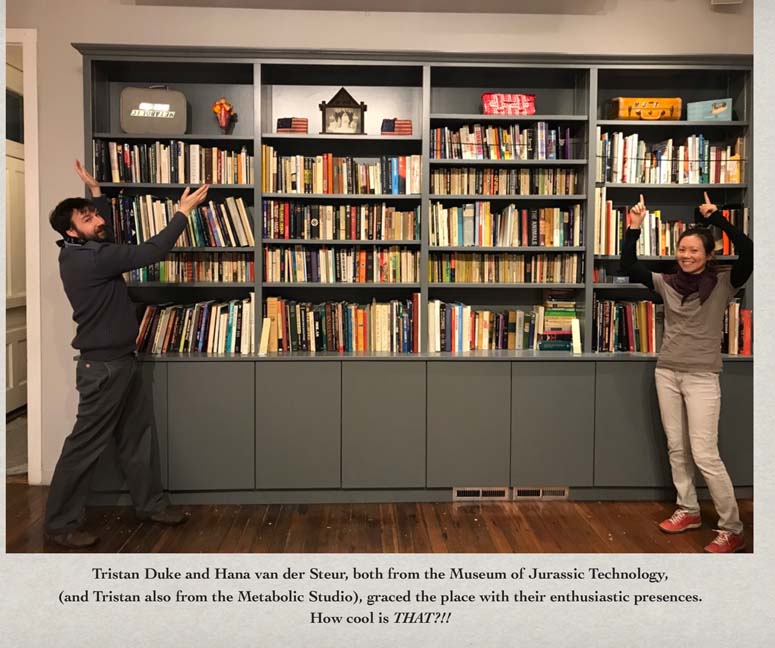

The First Ladies collection was discovered by Dr. Jacqueline Fulmer, folklorist in doll history and culture in Berkeley, and rescued by our dear friends and colleagues at the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles. Friends at the MJT graciously agreed to loan the collection to the RBSC, sharing our desire to soften the election season tension with attention to beauty and craft-of-the-highest order. The exhibition reflects Roger Brown’s ardent commitment to conjoining the so-called high style with the so-called not-so-high style, and the celebration of popular culture and popular crafts.

We extend sincerest thanks to Jackie Fulmer and Museum of Jurassic Technology friends Hana van der Steur, David Wilson, and Alexis Hyman-Wolff, and of course, to Doris E. Lane.

Brown Family

Roger wasn’t the only artist in the Brown family to fall under SAIC faculty member, artist/art historian Whitney Halstead’s spell. Greg Brown attended SAIC in the 1970s. In one of Halstead’s classes, he took the assignment to find and document excellent examples of the vernacular landscape to heart. Wandering all over creation with his radar tuned high, and camera at the ready, Greg got the goods! He allowed us to digitize 147 slides taken in 1976, and gave us the notebook logging his research. These enhance our understandings of: a) what ordinary people did to personalize their homes and gardens forty years ago, and b) Whitney Halstead’s creative, expansive teaching, and c) Roger Brown’s and Barbara Rossi’s collections of images from similar assignments. You can see Greg’s images here.

Greg Brown, photo of swinging baseball bat fence in Lance W. Kupisch, Attorney-at-Law’s front yard, 1976.

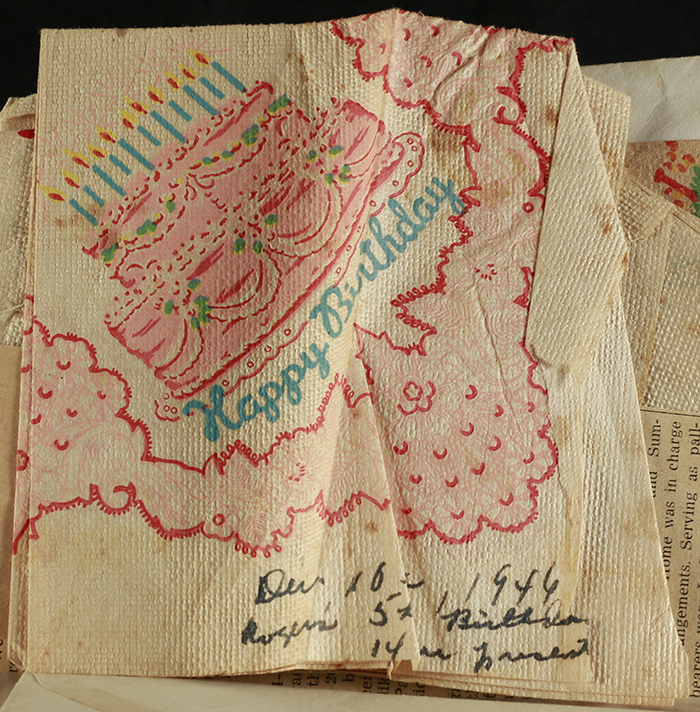

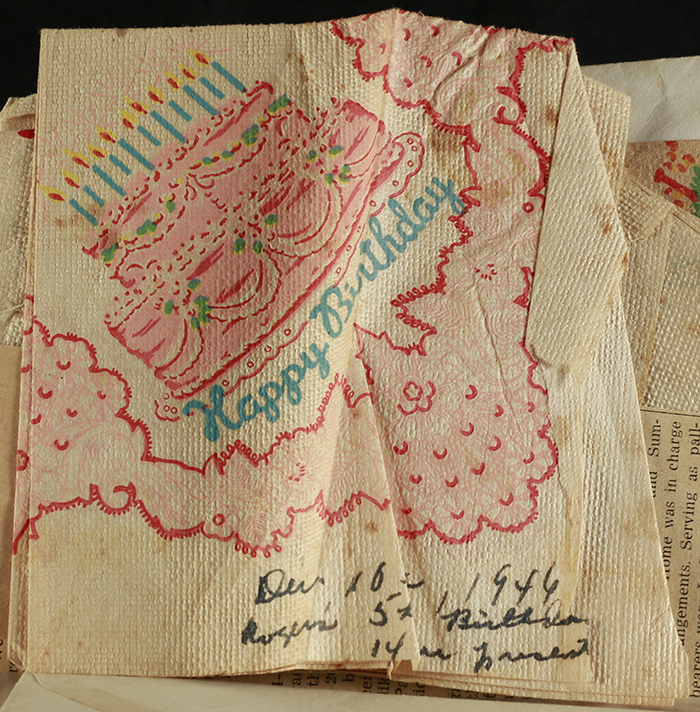

Greg also gave the RBSC an extraordinary scrap book that his mother made during 1945-46, the years her husband James served overseas in World War II. She saved the most poignant of scraps, including a napkin from Roger’s 5th birthday. Inscribed December 10, 1946, seventy years on the candles still shine.

Lisa Stone, December 22, 2016

Posted in Uncategorized on Friday, June 17th, 2016

Tours and group visits to the RBSC will be suspended from June 20 to July 11 for construction and collection organization. We apologize for the inconvenience.

Posted in Uncategorized on Thursday, February 25th, 2016

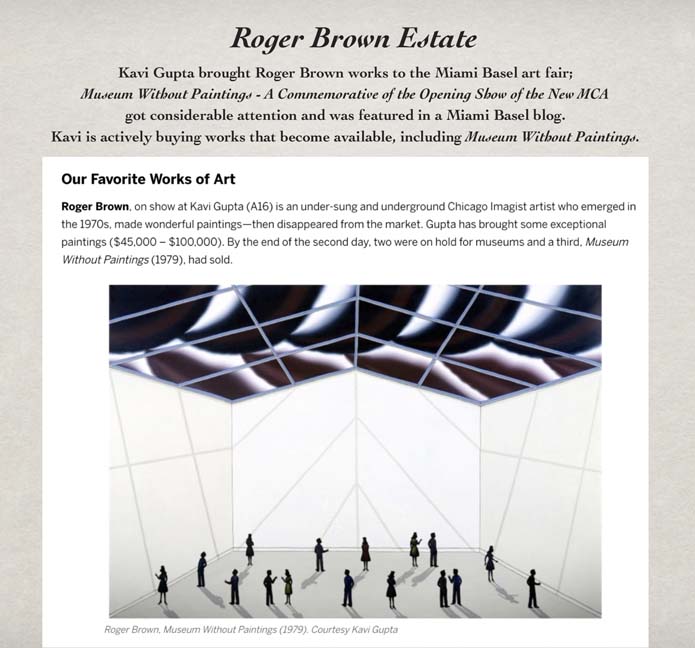

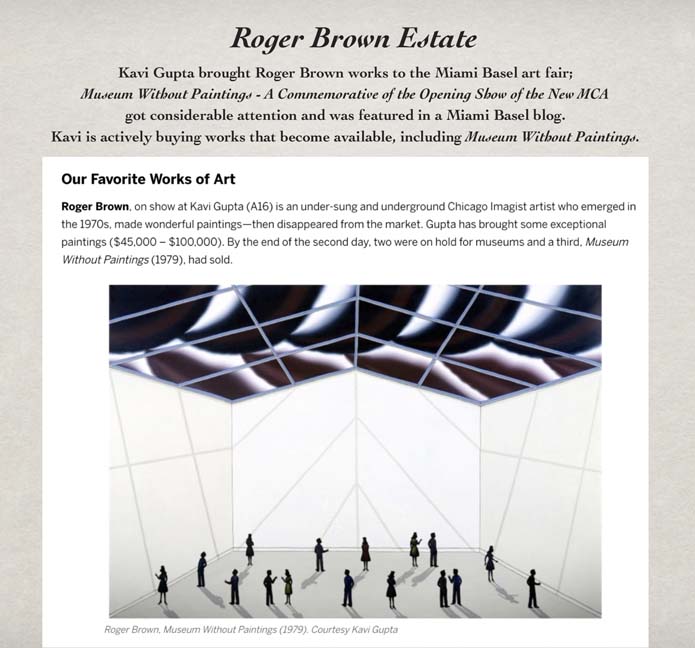

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) is pleased to announce the representation of the Roger Brown Estate by Kavi Gupta. Gupta and his staff bring enthusiasm and myriad ideas for expanding recognition for Brown’s seminal presence in late 20th century American art, and for introducing Brown’s work into new audiences, globally. We’re excited to work with the Kavi Gupta team and to fully support their efforts through the Roger Brown Study Collection archive and resources.

The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) is pleased to announce the representation of the Roger Brown Estate by Kavi Gupta. Gupta and his staff bring enthusiasm and myriad ideas for expanding recognition for Brown’s seminal presence in late 20th century American art, and for introducing Brown’s work into new audiences, globally. We’re excited to work with the Kavi Gupta team and to fully support their efforts through the Roger Brown Study Collection archive and resources.

We’re digging deep for archival materials to augment what will surely be an intriguing and provocative fall exhibition. SAIC’s Dean of Faculty and Vice President for Academic Administration, Lisa Wainwright, said “SAIC is deeply committed to the thoughtful management of the Roger Brown estate. We are tremendously excited by Kavi and his staff’s ideas and enthusiasm around the advancement of Brown’s important legacy. Watch this space!”

Russell Bowman/Russell Bowman Art Advisory represented the Estate since 2003. We’re ever grateful to Bowman (who closed his gallery in late 2015), and his staff, for their and efforts in promoting the art of Roger Brown and the Roger Brown Estate.

Roger Brown, A Painting for a Sofa: A Sofa For a Painting, 1995, oil on canvas/mixed media, 25 ½ x 31 x 9 in.

Posted in ALL THE NEWS on Saturday, January 9th, 2016

Guests!

This semester we hosted: 57 SAIC classes, classes from other schools, several receptions and public tours, 30 SAIC student researchers, 14 independent researchers, and uncounted, stray, sneak peek guests.

Above: Peter Exley’s Research Studio class

Good lookers!

Students working in the collection.

Once again, Patricia Rieger’s Curious Intimate Objects class made objects in response to a visit to the collection, and installed their works throughout the collection and property for the class critique. Above: ceramic objects by Francesca Villagrana in the central stairway.

Tom Burtonwood’s Digital Projects class make 3-d scans of objects in the collection, to use in original works of art.

We participated in the City-wide Chicago Open Archives event on October 8,

giving archives-obsessed guests a peek at some of our treasures.

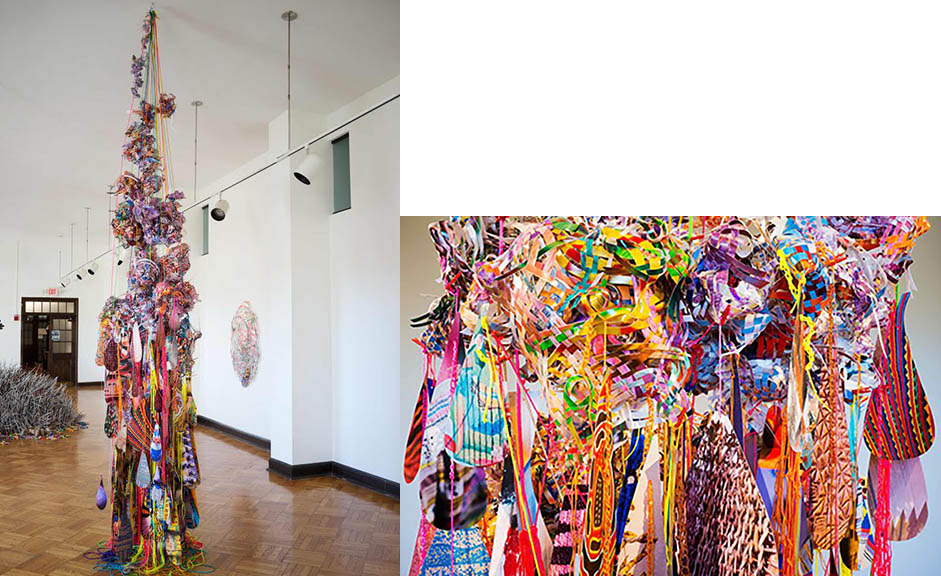

SAIC’s Shapiro Center for Research and Collaboration fellow, Gal Amiram, has been working as a studio assistant for faculty member Aimée Beaubien.

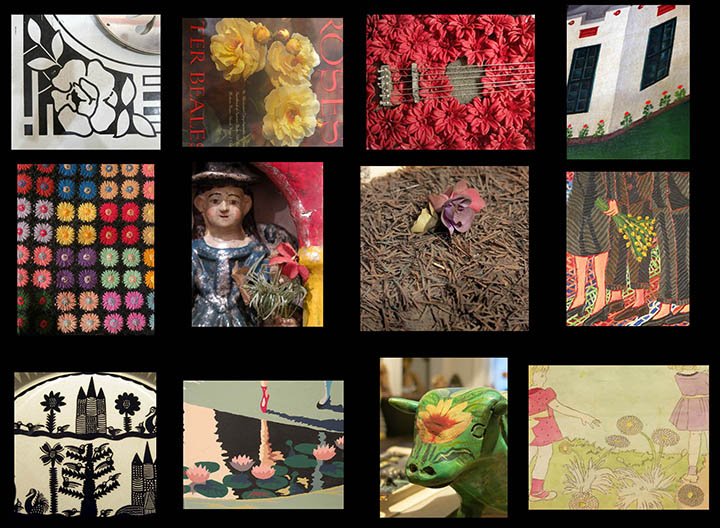

Together they spent a day a week throughout the fall, photographing objects in the collection, primarily woven works. Beaubien deconstructs and weaves her photos into beguilingly beautiful sculptures, which she’s deploying to a number of exhibitions.

Beaubien’s work at Form Unbound, Dominican University, November 5 – December 19, 2015

After 17 years of preserving the Roger Brown Rock House Museum in Beulah, Alabama, Greg Brown made the difficult decision to empty the building and sell it. Greg took two booths in a local antiques mall, and has been having fun arranging and selling items, from the Rock House, and his and Benedicte’s collections. We applaud Greg and the Brown family for making Roger’s last home, studio, garden, and collection come true, and for their heartfelt efforts in preserving the building and keeping it lively for so long.

RBSC staff participated in a series of lectures and tours of At Home in Chicago members at The Arts Club of Chicago.

Lisa represented the RBSC at the second lecture, discussing issues of preservation and access at historic house museums.

We’re pleased to announce that the National Gallery of Art acquired a number of works

on paper and exhibition ephemera from the Roger Brown Estate and the RBSC archive.

The National Gallery also received Brown’s painting Waterfall (1974) from the Corcoran Collection.

We’re thrilled that that major works by Brown are now in the Nation’s collection.

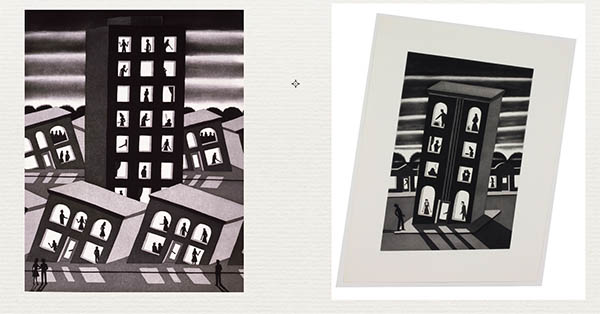

Left: Sinking, 1977, etching/aquatint. Right: Standing Around while All Are Sinking, 1977, etching/aquatint.

The painting-in-progress, below, was discovered on a separate canvas, stretched

under another painting during conservation in July 2013.

Sincere thanks to collector Steve Armstrong, who donated this unfinished painting to the Roger Brown Study Collection.

Sketch for the unfinished painting, from Brown’s 1970-1971 sketchbook.

We heartily congratulate RBSC steering committee member and Brown’s dear friend (and ours!),

Barbara Rossi, on her outstanding exhibition BARBARA ROSSI: POOR TRAITS at the New Museum, New York.

There’s much more to tell but we’ll close for now, and promise more missives in the coming year. Thanks to the stellar RBSC staff and SAIC faculty and administration. Warmest wishes to all. Lisa Stone, curator, January 2016

« Older Entries