Carlos Antonio Piñón (BFAW 2017) is a Chicago-born artist and writer examining the ways people interact with words and language. His work often questions the expectations of books and texts insofar as to reject them both on and off the page.

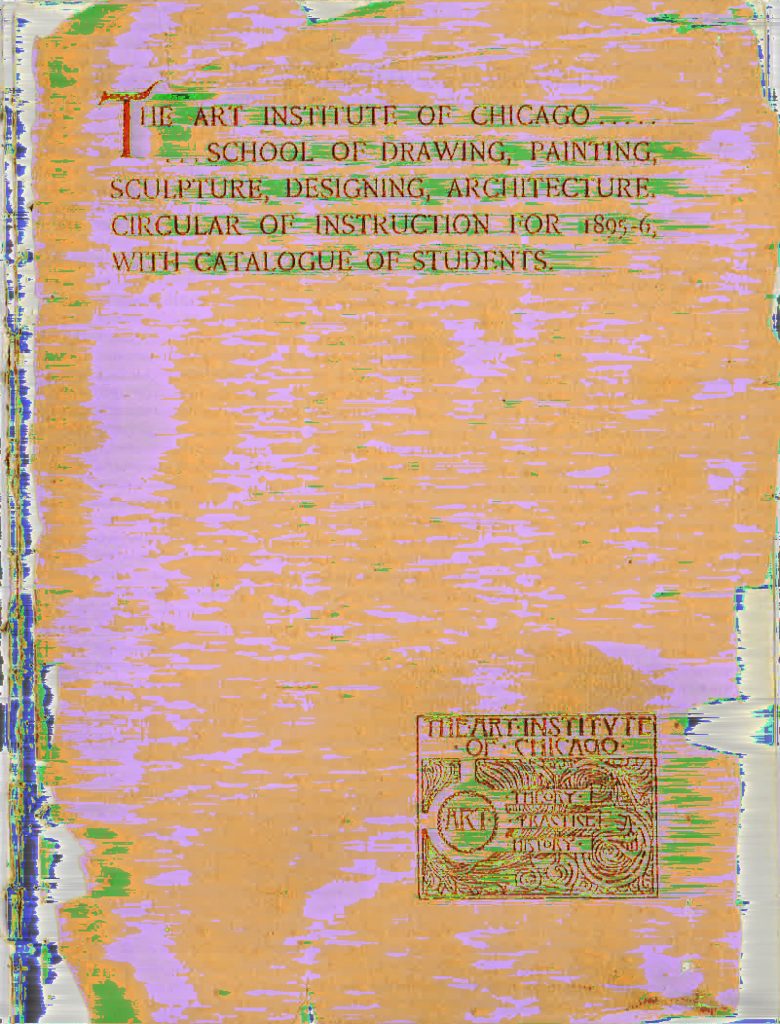

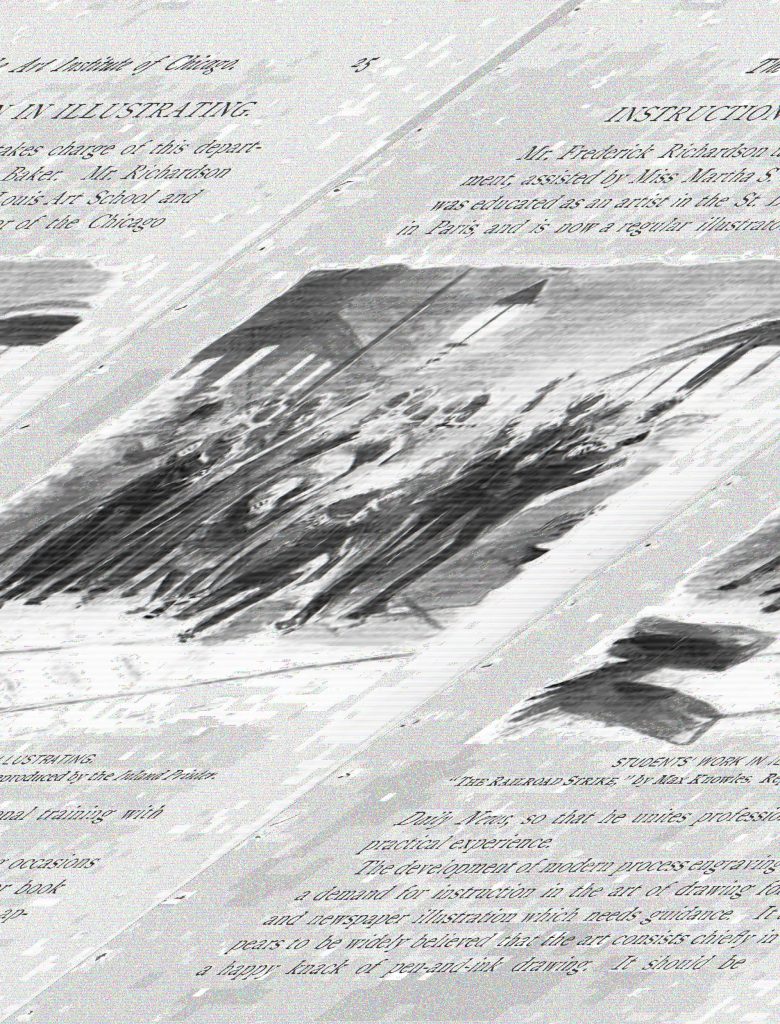

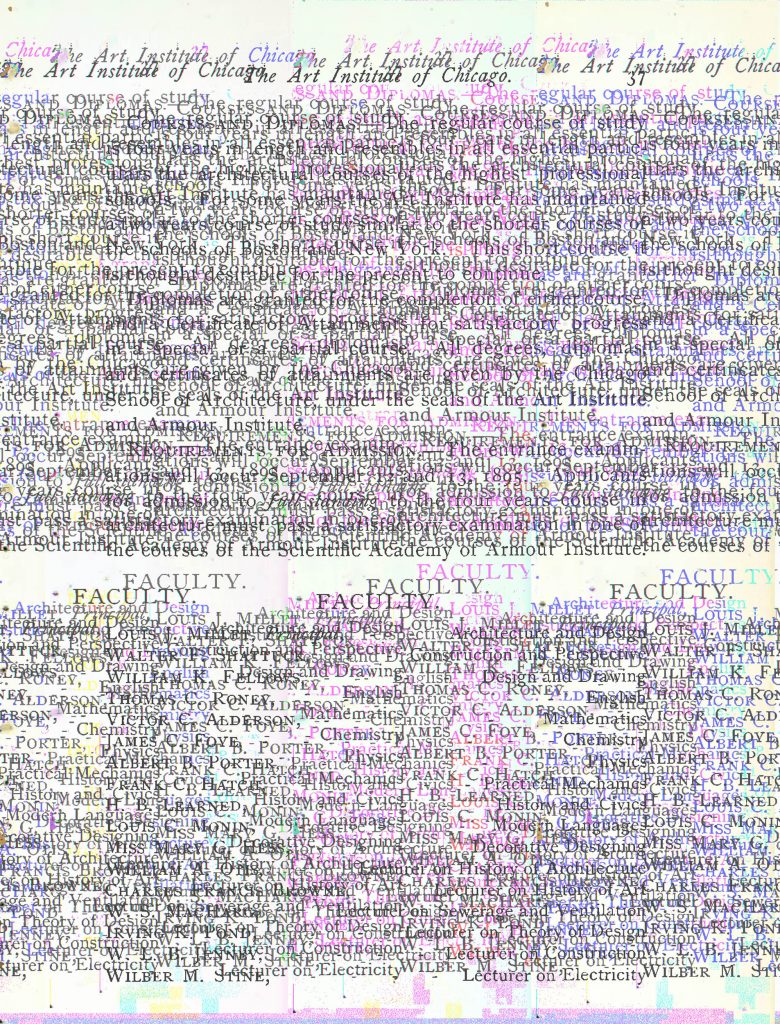

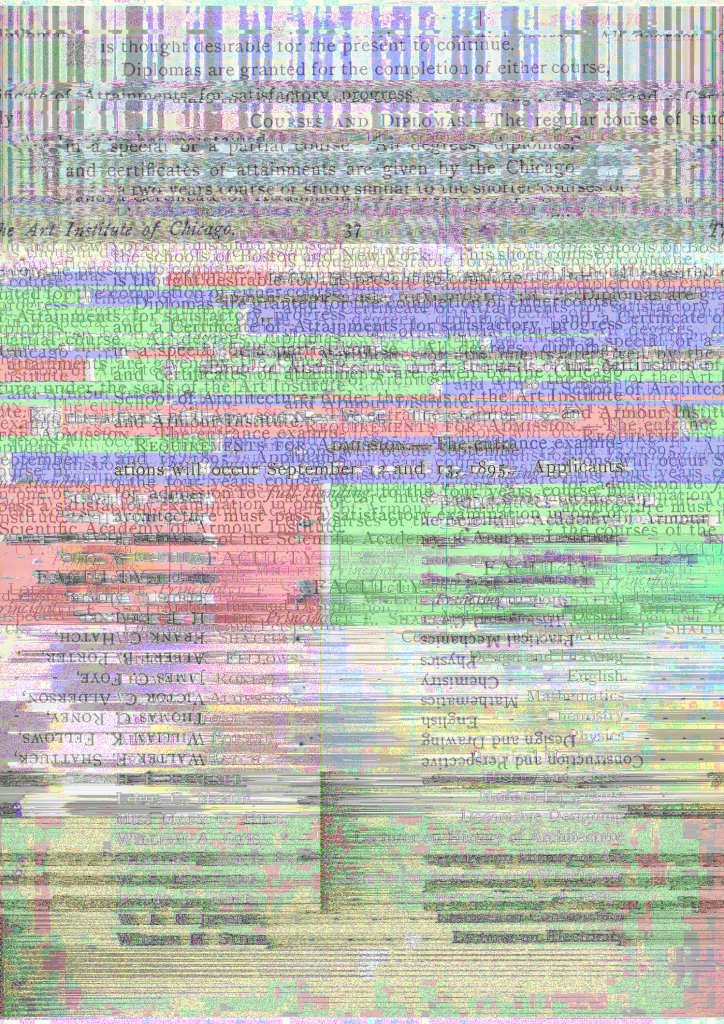

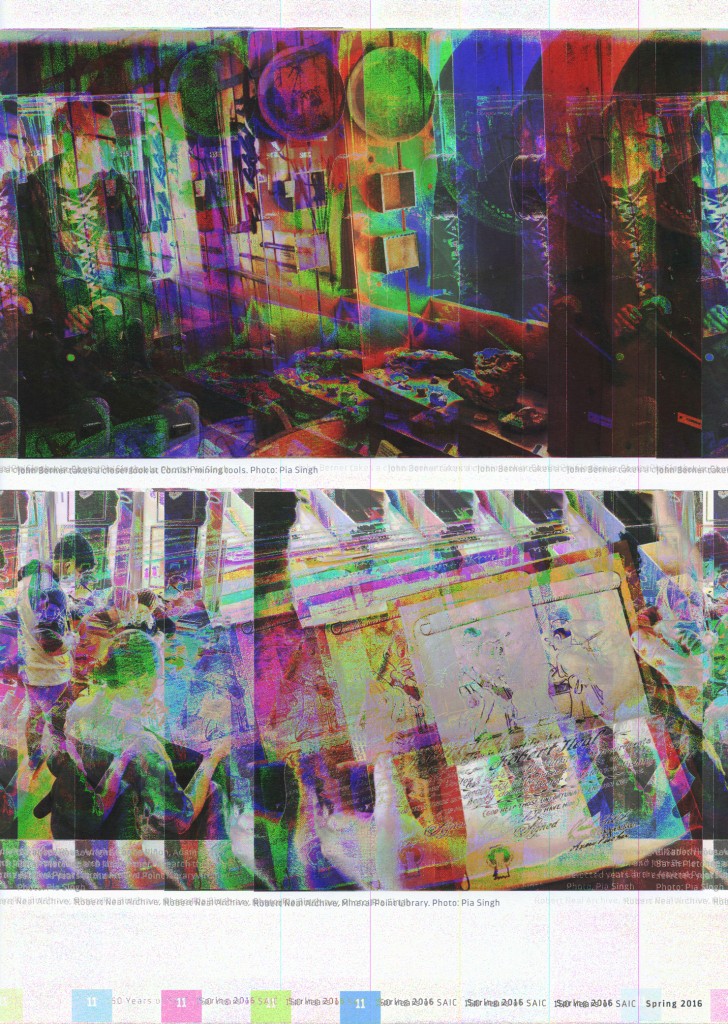

Misprints seeks to reinterpret past and present SAIC publications through the process of databending sonification. These publications include the 1896 course catalog, which is an institutional record of what the School was like that year; the 1982 Over a Century book, which is a set of personal recollections of the School’s first 115 years edited by Roger Gilmore; and the Spring 2016 E+D magazine, which celebrates what will come next after these 150 years. Scans of these publications are manipulated through a digital audio workstation and then exported as glitched, illegible image files. The work exists first as the three publications subjected to databending, and second as a durational broadcast of the audio output from the sonification process at Free Radio SAIC. Listeners will find difficulty listening to the audio output due to nature of creating sound from an image file, just as readers will find difficulty interacting with the manipulated publications.

Event: You can tune in to the broadcasts at freeradiosaic.org/shows/misprints

Original air dates:

Episode 1: A Recollection (3/19/2016)

Episode 2: A History (4/1/2016)

Episode 3: Remembrances (4/9/2016)

Episode 4: Over a Century (4/15/2016)

Episode 5: New Beginnings (4/16/2016)

Previously On View: 14th floor of the MacLean Center, 112 S. Michigan Ave.

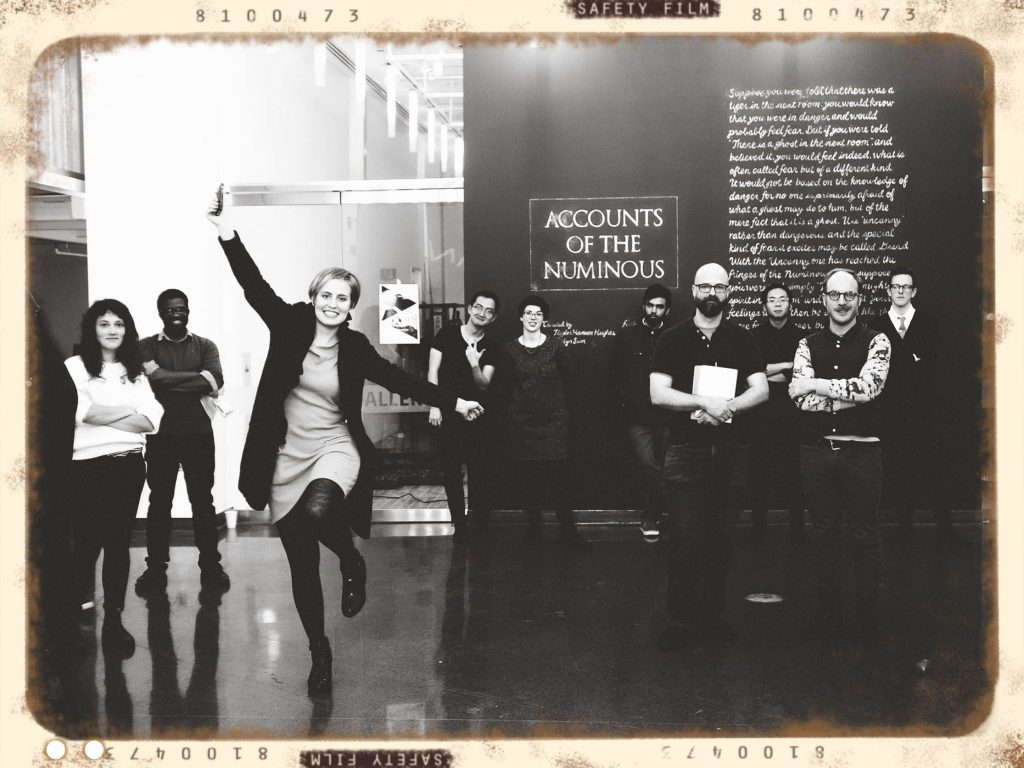

Missteps, the precursor of Misprints, was a three-part installation involving several monitors showcasing glitched images from the 1896 SAIC course catalog. The work was installed in the Leroy Neiman Center at 37 S. Wabash Ave. as a part of the Telegraphic Fields (First Transmissions) exhibition celebrating the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s 150th year anniversary.

Thinking about text and books in the context of the archive immediately brought me to the idea of aging media. Page after page yellowed with some of the more crisp ones falling apart by the touch. In doing research for a different subject that semester, I came across an old letterpress book where the words on one page somehow seeped into another, which further influenced the way I perceived these old documents.

In many ways, the little mistakes I found in old documents didn’t feel all too different from the glitch work I was making. Instead, making a typo on a typewriter meant you had to go over your mistakes with X’s. I intentionally subjected scans of the catalog through sound editing software and back as a way of using the archival material the wrong way. The process of using a tool for something other than its original intention to initially immortalize a decaying document into the digital realm and to simultaneously reinterpret it into something else entirely seemed like an appropriate response to me.

I chose three separate, but visually appealing pages: one was the title page, one had an image, and the final page displayed text in an interesting way. As there are many effects in Audacity available, I limited myself to seven each. When it came to install at the Leroy Neiman Center, figuring out how to display all twenty-one images became an issue. Instinctually, I wanted to keep the altered images digital, and so video was the compromise. Even still, working out how to portray the twenty-one images remained unknown to me.

The first iteration—which also managed to make its way into the exhibition—was to display them as a triptych on a single monitor with varying speed (fast, slow, average) for the seven images. The intent was to have them play all at the same time so that the audience can choose which to look at, then switch. As I was essentially rendering a video from a GIF, I had to slow the rotation several times because you couldn’t see any of the detail. Part of the issue was that the monitor too far from viewer.

The detail in each image was important to me, and through help from Mark and Nick, we managed to obtain access to the three monitors in front of the elevators. That way, they would be displayed bigger, and anyone could step right up to them. With the physical catalog also present itself, the exhibition felt wholesome. The three monitors all portray a separate page consisting of seven different glitches each as you walk in from the outside.

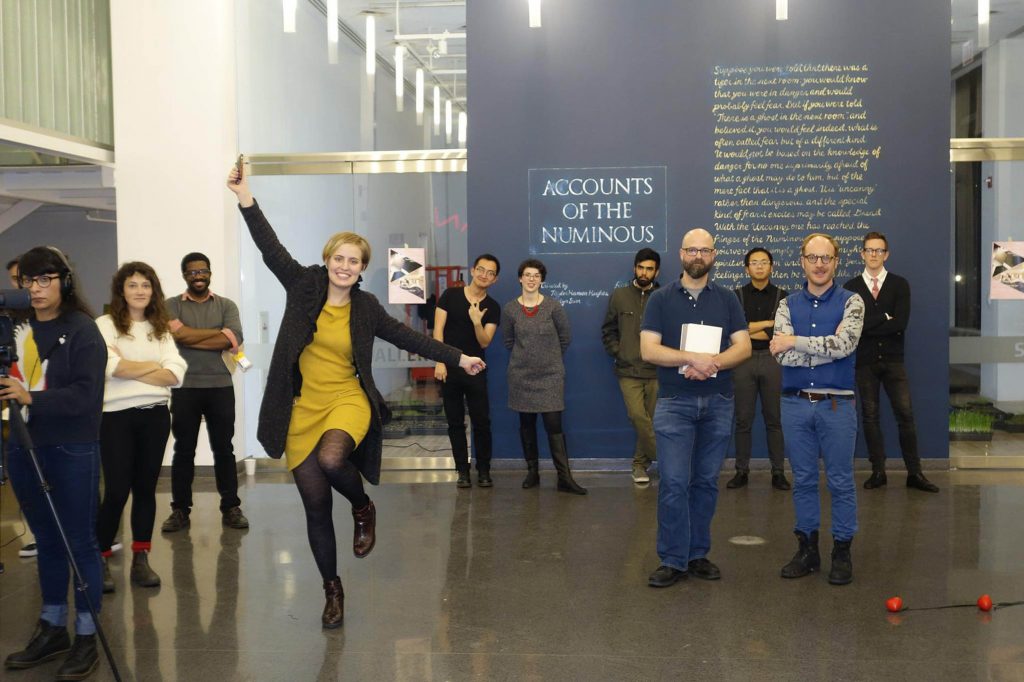

“Today is November 17, 2015. You are now a part of the the Archive.”

Days after our exhibition opening, we held our Telegraphic Fields (Live Transmissions) event. For this project, Dong Chan Kim and I collaborated in a performance which began with Dong Chan photographing the audience. He would then edit the image he took to mimic an old photograph. After, I would manipulate the original image a second time via databending sonification. Once the two edits were made, all three versions were uploaded to Facebook under the hashtag #SAIC150, and then we informed the audience that they had been archived.

Reinterpreting text through glitch in context of the archive has actually been a fantastic intersection of many different thoughts. In working with Dong Chan Kim by inviting the audience into the archive, one of the things that stuck with me is making all of this material available. After all, books are meant to be read and engaged with, not just stowed away. What’s the point in keeping something preserved if no one ever interacts with it? When I first uploaded documentation photos, an online friend thanked me for making the exhibition available to those who can’t be there, and it struck me that it would be virtually impossible for most people to engage with the material unless it was explicitly made public, which is what we did by posting online.

The photographs continued to garner likes, shares, and comments for nearly a week after we posted them. Many of the notifications were actually from people who did not attend the show.

Dong Chan and I spoke a lot while developing our live performance. As a photographer, he was interested in the databending sonification process I used for Missteps. That’s when we came up with the idea of making multiple versions of the same image: one that I would glitch, and one that he would turn black and white like an old photograph.

We decided that it couldn’t just be any photograph, but it had to be one that we took during the performance. Realizing this, we understood that we would inherently be creating a documentation of the show. Furthermore, we also knew we would be inviting the audience to become archival material themselves. Thus, sharing the images online was agreed upon the both of us as a vital aspect of our show.

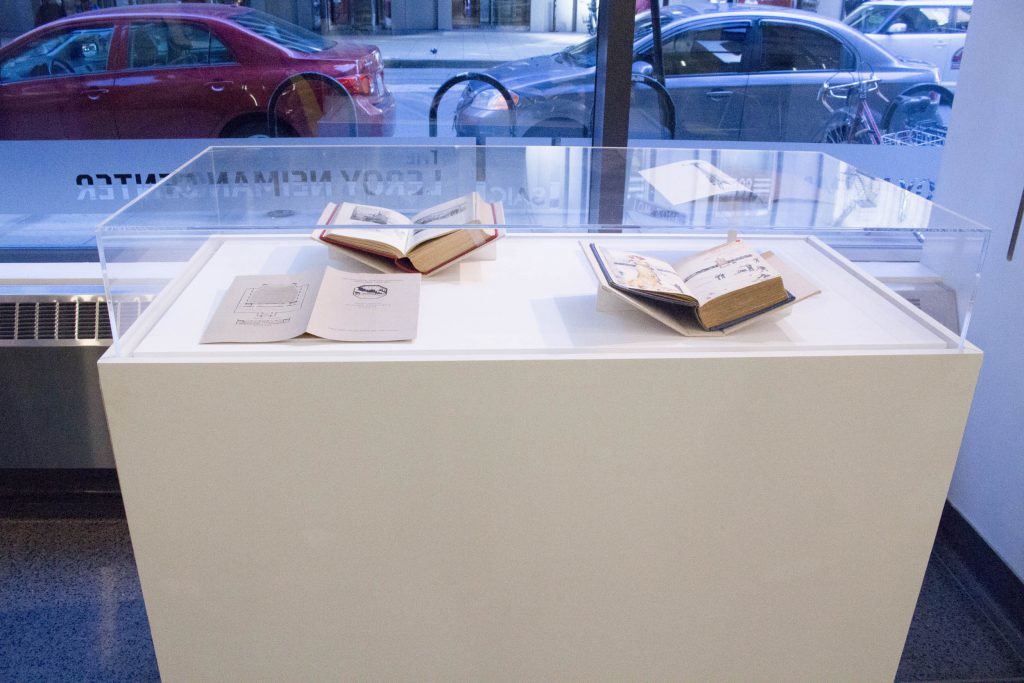

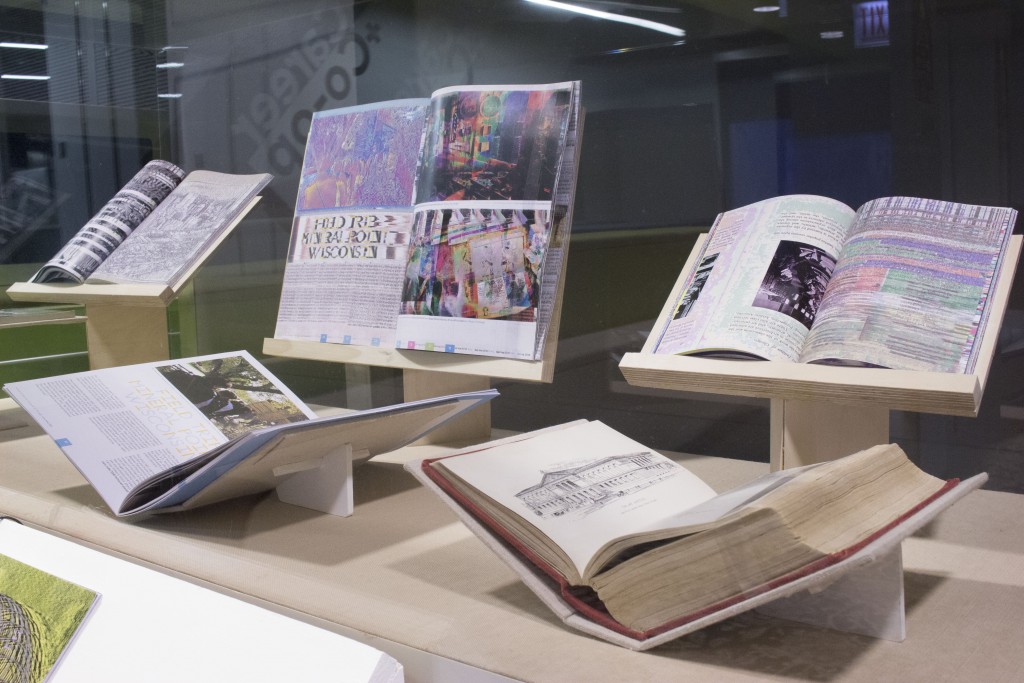

Expanding from last semester’s work with Missteps, Misprints was three-part installation involving a vitrine showcasing glitched versions of the 1896 SAIC course catalog, the 1982 Over a Century book, and the 2016 Spring E+D magazine. The work was installed in the MacLean Center at 112 S. Michigan Ave. as a part of the Telegraphic Fields (Next Transmissions) exhibition celebrating the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s 150th year anniversary.

For this iteration, I chose two other books, in addition to the course catalog, that were relevant to my time at SAIC. In January 2015, before I signed up for SAIC 150: Repeat Transmissions, my boss at the Office of Institutional Advancement tasked me to make scans of Over a Century at the Ryerson Library in preparation for the anniversary. Because I had to keep the book in good condition, I couldn’t lay the pages at, and therefore, the quality scans progressively grew worse until a majority of the latter half featured part of my finger.

Both the catalog and Over a Century are similar since they are black and white books with the occasional photograph, and their pages are slightly yellowed. The main difference is that while I was able to get nice, clean scans from course catalog, Over a Century uniquely has my thumb. Then in October later that year, our class took a eld trip to Mineral Point, Wisconsin. I had the honor of writing an article about the trip, which ended up being featured in the Spring 2016 E+D magazine produced by my office. I knew I had to make this my third book to glitch, not just because of my article, but because the E+D is entirely in color—something that the other books lacked.

For me, being in between the crosshairs of writer and artist, I have been working closely in ways to explore the ways people interact with words and language. Part of my practice is creating glitch art through databending sonification—something I learned while taking Wired: Imaging and Web my first year at SAIC, and something I would later pass on as a teaching assistant in the same course. Today, Wired is no longer offered at SAIC.

I hadn’t found a way to incorporate this skill into the rest of my practice until Missteps. Initially, I didn’t think glitching pages from a book would yield anything even mildly interesting, but I was wrong. After weeks of experimenting with all of the effects and their settings, of mixing multiple effects together, of copying and pasting different portions of the audio, of splitting the audio and manipulating the individual mono tracks, I created something unique to me. I felt like I had to share this skill like I did when I was a TA and during the Telegraphic Fields (Live Transmissions) event last semester, so I began by holding a live stream on YouTube, teaching friends and strangers my method.

“Shout-out to those listening to this in the future as archival material.”

Because glitching a scanned page of text essentially renders it unreadable in most cases, and because glitching with Audacity requires converting images files into audio files and vice versa, I held a five-week radio show on Free Radio SAIC playing the entirety of the audio from Over a Century.

Inherently, just as the text is illegible, it’s hard to listen to the audio. The introduction for every episode consisted of the project description, a statement on which pages I would be broadcasting, and a warning for listeners to begin at a low volume and raise until comfortable.

In the five weeks at the radio show, I personally listened to 15 hours of rhythmic clicks, pulsing static, and horrendous screeches; but I wasn’t alone. On some days, I had an audience engage with me on the Free Radio SAIC chat. On other days, I had friends listening with me in the radio booth, enjoying a pizza on that Saturday night. But on most days, I wasn’t sure if I had an audience at all. After all, how many people would willingly listen to three hours of harsh noise on a weekly basis?

The weekly broadcast (if it could be called that) was not without its trouble. The second week I was supposed to air (March 26th), I was informed by security that I didn’t have access to the radio key. There was nothing I could do and the broadcast had to be rescheduled for Friday, April 1st, which aired without an issue.

Having just completed a successful transmission the day before, I was con dent that the show would return to a regular schedule on April 2nd. Due to an unknown error, while I did broadcast live, nothing played. I spent three hours thinking the audio was playing on air when I was the only one able to listen in the radio booth. I was wrong and had to reschedule the third episode.

The next week on April 9th, I was prepared to broadcast and have something available for the Free Radio SAIC staff to archive no matter what. This time I was able to broadcast, except for a separate unknown error where my voice was ironically glitched out, too, and nothing sounded like it was supposed to. I submitted the back-up recording I made separately, but kept the glitched out version.

The last two episodes aired without a problem. At the end of every episode, I made a shout-out to those listening to the recordings as archival material. And that’s how Misprints exists now, archived by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

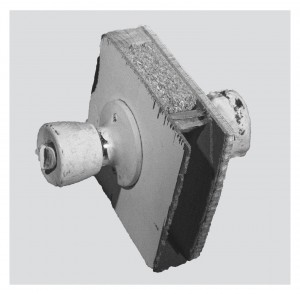

Misprints, 2016, Glitch books alongside their original prints, audio on headphones from databending sonification.

Misprints, 2016, Glitch books alongside their original prints, audio on headphones from databending sonification. Misprints, 2016, Glitch books alongside their original prints, audio on headphones from databending sonification.

Misprints, 2016, Glitch books alongside their original prints, audio on headphones from databending sonification. Select image from Misprints, 2016, Databending image from the 1982 Over a Century book edited by Roger Gilmore.

Select image from Misprints, 2016, Databending image from the 1982 Over a Century book edited by Roger Gilmore.