The two following texts work in tandem. They talk about the same project, from different points of view. A Regurgitation is a Song is a Spell (Consultations to Recreate the Colonial Disease) is a project by Luisa Ungar for the Stomach and the Port, the 2021 edition of the Liverpool Biennial. Initially meant to parasite the format of a guided tour around the city, activating several places linked to colonial history, the project dramatically shifted to adjust to the possibilities of the pandemic and took its final shape as private one on one calls between a clairvoyant and whoever signed up for a half an hour consultation. The first text, a sensorial and rhythmical account of an audience member receiving a call, is written by Carolina Cerón Castilla, a Colombian curator based in Bogotá. The second text is a conversation between Luisa Ungar and Inés Arango Guingue where processual aspects of the evolution of the work are explored, an example of how intuition and improvisation can be used to carry on with a project among difficult circumstances.

A conversation between Inés Arango Guingue and Luisa Ungar on Ungar’s work A Regurgitation is a Song is a Spell (Consultations to Recreate the Colonial Disease) (2021).

English version

Inés Arango Guingue: Manuela Moscoso named this edition of the Biennial “The Stomach and the Port,” creating a direct relationship between that part of the human body and the city’s harbor, stating that “The stomach can be thought of as the port to the gut, a site where the outside environment comes to dock. […] A stomach can’t ignore so-called foreignness and needs to engage with it, either by prepping it to transition into the body cells or by slowly deciding to send it back to the mouth.” How did you engage with this framework as an artist invited to create a new piece?

Luisa Ungar: When Manuela invited me to be part of the Biennial, we started an enriching conversation: the metaphor of the stomach led us to talk about notions such as porosity/parasites/fluids and, from there, to work from the body and with the body. I wondered about so called foreign elements and if these somehow implied some resistance to that colonial machine “that swallowed everything.” Seeking to “enter” that pit of the stomach, I approached some archives and collections of the port. I gradually found communicating vessels that guided me through Liverpool. I usually work this way, identifying specific strings that allow me to pull some of the colonial circuits that cross us in the present, following clues as signs of orientation.

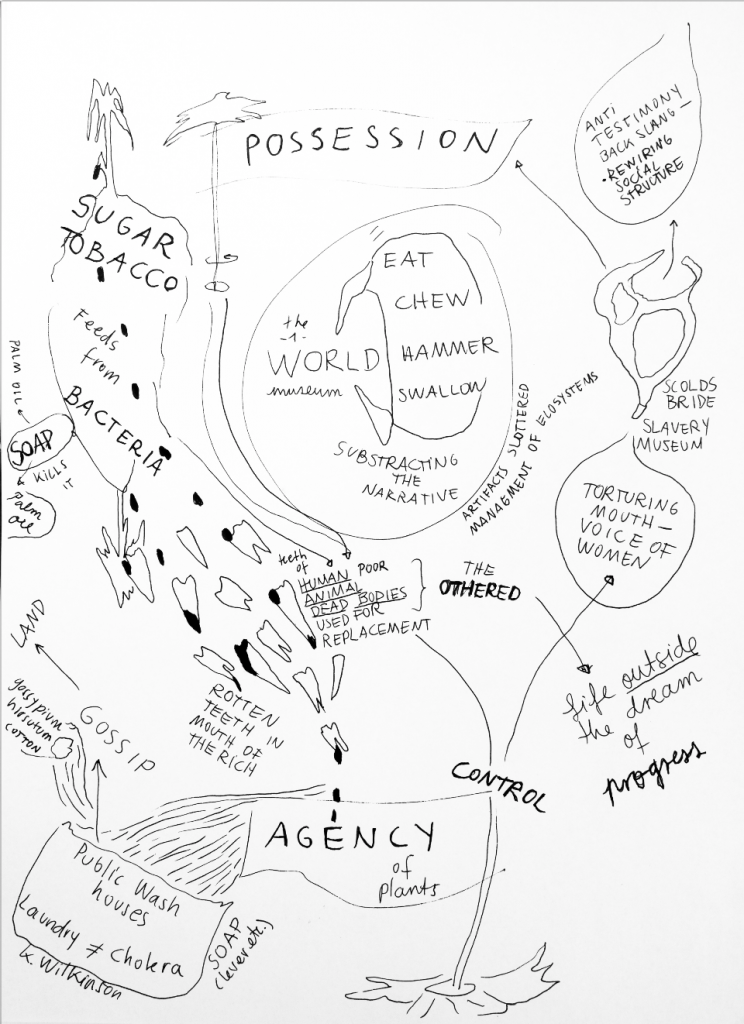

On the first research trip, I reviewed archives at the Meyerside Maritime Museum, some from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine’s collections—Liverpool has active tropical disease research centers like other key port cities during the colonial period—and others from the University of Liverpool’s Dental School and the International Slavery Museum. I also explored the World Museum, its space crammed with pieces of various kinds from different regions of the world, manifestos of power and control, forms of systematization, and classification of knowledge and extraction.

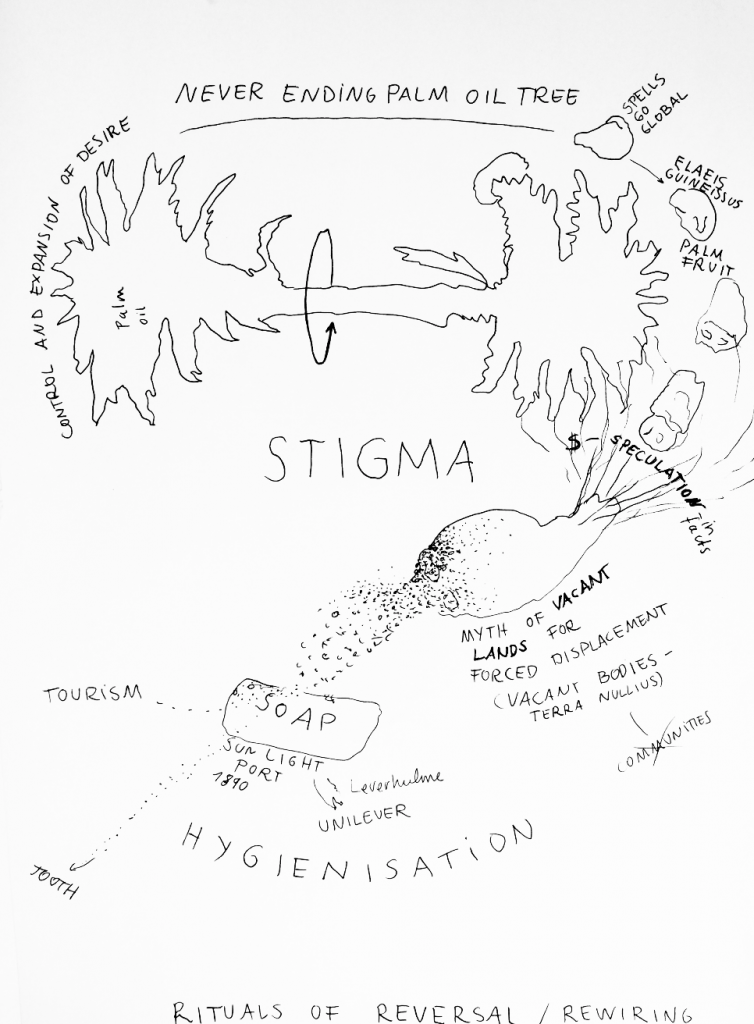

Some clues in this scenario led me to think about notions of contagion, possession, stigma, and hygiene and, simultaneously, in manifestations of kinship and porosity. Some objects emerged as nodes or “keys” in the circuits I was identifying and functioned as triggers with which I began to obsess, seeds that encapsulated incanting spirits of the past.

One of these items was teeth. The University of Liverpool School of Dentistry has an extensive collection of teeth. These teeth are a “place” (a part of the body and a part of the world) where the colonial device begins to manifest itself: teeth start to be damaged by the importation, first exclusively and then massively, of sugar and tobacco. And the teeth of the upper classes began to be damaged first because they were the first to have access to these new products. The first dental prostheses were made with solid blocks of hippo, walrus, or elephant ivory; the next ones were extracted from the mouths of the dead soldiers in the battle of Waterloo or of people without resources who sold their teeth to survive: in these pieces, we can glimpse both the agency of the plants extracted from the colonized territories and the social practices of segregation (of humans and non-humans) generated by the growing capitalist system.

For me, locating the system in which the object is inscribed opens up its meaning and its use in terms of performative possibilities. In this system, one thing leads to another, and so possible relationships emerge that open up its meanings. Understanding an object in its narrative system allows me to play with that system in some way. In Liverpool, dynamics that emerged in territories separated by enormous geographical and cultural distances, fed by the transatlantic traffic of enslaved people, converge and knot together. The popularization of soap in the city, for example, began with the importation of palm oil, which facilitated the creation of companies such as Lever & Co, which around 1884 began mass-producing Sunlight soap, taking advantage of the Congo’s recent importation of palm oil produced by enslaved people. Over the years, Lever’s company would become Unilever, one of the world’s largest economic conglomerates. These objects were related to others that appeared in this system of relationships; Thus emerged the scolding bridle, or “brank,” (an object of torture used to hurt and humiliate women whose speech was deemed offensive) in its attempt to censor voices that implied resistance to the booming system (in the International Slavery Museum), and, at another end of the spectrum, an object such as the “headdress worn by naidugubele healers during consultations, Ivory Coast,” part of the African collection of the Museum of the World.

IAG: How did this materialize in your project?

LU: I create the scripts of my performances in several layers, and the “how” emerges from the research itself. Revisiting epistemologies that question dominant narratives leads me to work with conversations I have with people I meet during the research. Orality, conversation and gossip are important elements in my work, I am interested in speculative systems of knowledge. We talked with Manuela from the beginning about the place of conversation in my work and how it is transformed into a means of contrast that is activated from the elements found in archives and collections which serve as clues, as I mentioned before. In this constellation, and in different senses, the mouth occupies a meaningful place.

In Liverpool I took city tours, and had various chats with locals following the threads I mentioned, talking with people about contagion and infection. In the MFA in performance at Hope University, we had meetings with Silvia Battista, Anna Laura Alifuoco, and their students. We also talked with the curator of the World Museum’s collection of African artifacts about notions of possession, stigma, and contagion, and with people from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, an institution that pioneered the “single-prick blood tests” developed to identify diseases brought back by soldiers fighting wars in tropical countries. The pricks, the contagion, and the notion of stigma and possession gave me clues to understand the “how” of the project. I started visiting the community drama sessions at Playhouse/Life Rooms to identify possible non-acting women we could work with. While I was working on this, the pandemic hit. I had to quickly leave Liverpool and fly to Bogotá.

IAG: Since your on-site research was abruptly halted by the pandemic, how did this project evolve while you were no longer in Liverpool?

LU: From each other’s distance and confinement, we kept meeting periodically with the production and education team of the Biennial and continued the conversations with Manuela. During the first months, we believed that it would be possible to do the project as we had initially conceived it and that we would only have to make some variations. It was going to be a performance in public space activated by the intersection between objects, narratives circulating in the city, and the responses of the people who came into contact with these mixed stories. It would be presented throughout the Biennial as a periodic guided tour, almost daily, and it would take place in the center of the city: from the World Museum, we would walk to St George’s Hall. Working on the action in public space in Liverpool from my room in Bogota had a kind of liberating effect. At the same time, the education team was eager to go out and try out the scripts as an excuse to get out of their homes.

As the pandemic progressed, we had to change the conditions of the piece: new regulations were constantly appearing that implied changes in the number of people allowed to be in groups in public and private spaces and the number of possible groups. We had to keep modifying sizes, number of spectators, and the voice amplification system in the locations, looking for mechanisms that did not require physical proximity between the public and the performers and thus reduce the possibility of contagion. Several times we had to find out about different sound amplification schemes. Each time the allowed size of the audience groups was reduced, the required distance between each “cluster” also increased. This implied some exciting challenges for the piece; thus, the notions of porosity, contagion, and kinship took on other dimensions. The online conversations were becoming more and more intense, and we were all in that state of pandemic, locked in the intimacy of our homes, talking and looking for ways to figure the piece out. At one point, we had to accept that we would not have a live public program at the Biennial.

We were looking at options such as turning the piece into a sound work when I realized that virtual conversations were the key; it was through conversations that other forms of contagion were possible. The pandemic made us return to the intimacy of physical space while overexposing us to virtuality. Image-less conversations also responded to this issue. I began to review the call center idea. I liked to play with references taken from call center culture, remote work, and the implications that those modalities of labor have, even for the field of art. In addition to the idea of contagion, by that time the mouth and the voice were already essential elements of the project to both the research and the situation we were going through.

IAG: Working with clairvoyants was an essential part of this work. Let’s talk more about how the work with these people connected to the on-site research you did.

LU: The work with seers had to do with several factors that occurred in the process, because of the research and because of the change in the conditions of production generated by the pandemic. All this led to new connections that responded incredibly to the clues found along the way.

On the one hand, the figure of the clairvoyant allowed me to create a connection between our current situation and the colonial disease. What role plays the narrative tool in all of this? Could we create a script that responds to one’s own life and tackle some of the elements present in the research? Working with clairvoyants allowed me to communicate that the transmissibility of history is not possible, that we can only tear it out of its context, fragmented and destroyed, crumbled and decomposed. They emerged as a key that could link the voices in different parts of the world with the locals; their work allowed porosity, and with them the caller could interact with some of the materials encountered while, at the same time, acknowledging the presence and agency of bacteria, spirits, animals, divinities, viruses, etc.

On the other hand, the research done in Liverpool talked about hygiene, contagion, gossip, and the persecution of women, but it also referred to the presence of women’s organizations in the city. It is impossible to review the colonial apparatus in the area without hearing about the presence of the forms of segregation that I pointed out to you at the beginning. When the colonial device begins to operate, there are presences that, from “inside the stomach,” are an obstacle and a threat to the growing capitalist system.

Following Silvia Federici’s perspective, I refer to the hundreds of thousands of women murdered in the framework of the persecution of the supposed “witches.” In Liverpool, besides the scold’s bridle (or “brank”), an instrument of punishment used to prove that these women were possessed was the Ducking Stool, which consisted of sinking them tied to chairs in the water of the canals of the city so that they would confess (one of such places was by St Patrick’s Cross). Another form of abuse was pricking, trying to check if blood drops were coming from their bodies; they also searched for supposed “marks of the devil ”: traces on their skins that would prove their possession. In the 20th century, it would be demonstrated that these marks were granulomas resulting from the bite of ticks, another agent coming from America, which mainly bit farm and orchard workers and whose bacteria transmitted Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi). Authors like M. Drymon have studied how afflictions associated with witchcraft kept appearing in the same places where this disease might have occurred. Relevant figures had emerged in the investigation, Mary Wilkinson for example occupies a relevant place in late nineteenth-century Liverpool, by demonstrating that cholera did not appear at washerwomen’s meetings. The work then resonated in its connections: forms of knowledge and practices that have been stigmatized and marginalized by the modern-capitalist world, and what various materials from the city could say about potential contamination between regimes of knowledge, revising forms of deprivation of women’s voices in connection to local history.

IAG: The threads you wanted to pull were quite extensive. How did the project begin to take shape after all this research?

LU: The decision to work with phone calls resulted in the piece entitled A Regurgitation is a Song is a Spell (Consultations to Recreate the Colonial Disease), where we worked with a group of clairvoyants around the various types of material from collections and archives in the city. The experts were available to the public to answer questions via phone calls. We invited the callers to “ask a question, share a concern or an urgency.” Anyone from any part of the world could call.

When I decided to work with clairvoyants who identified themselves as women, we started the process of the casting to find them. Perhaps this was my favorite part of the whole process. With them, I put into play the critical elements of the script; from the research material and depending on the skills and methodologies of each one of them, the consultation was developed. The conversation brought together the current situation of the caller with the seer’s reading system and the elements of the collections. We did not invent the material. It was all part of the research. For me, drawing attention to the continuous work of simulating reality is essential.

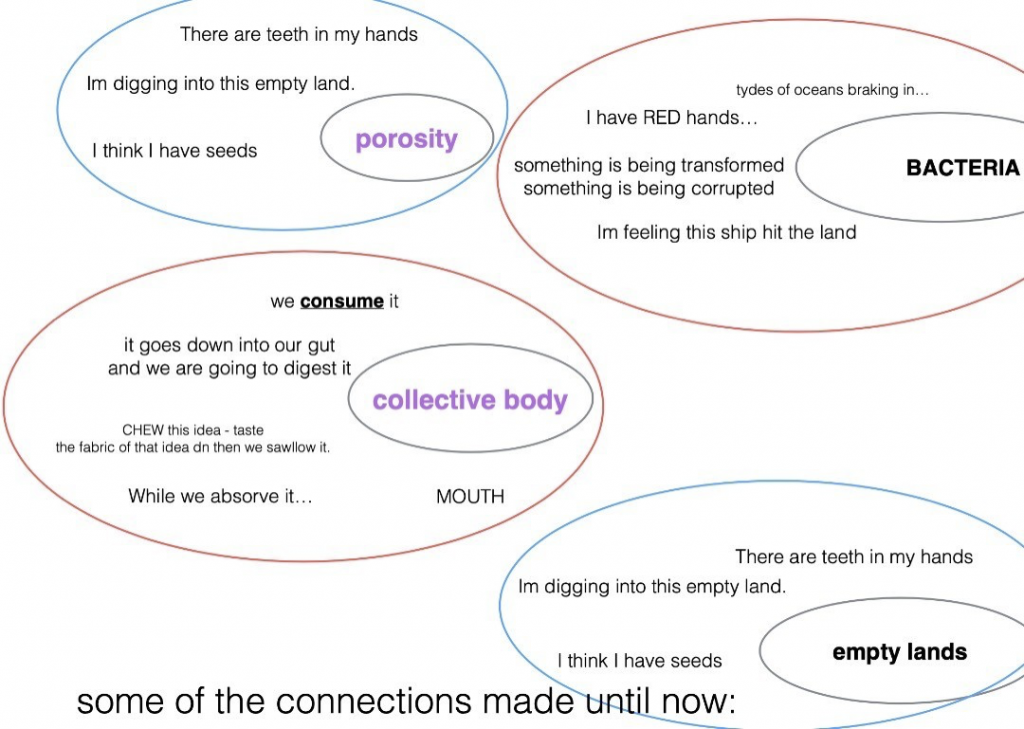

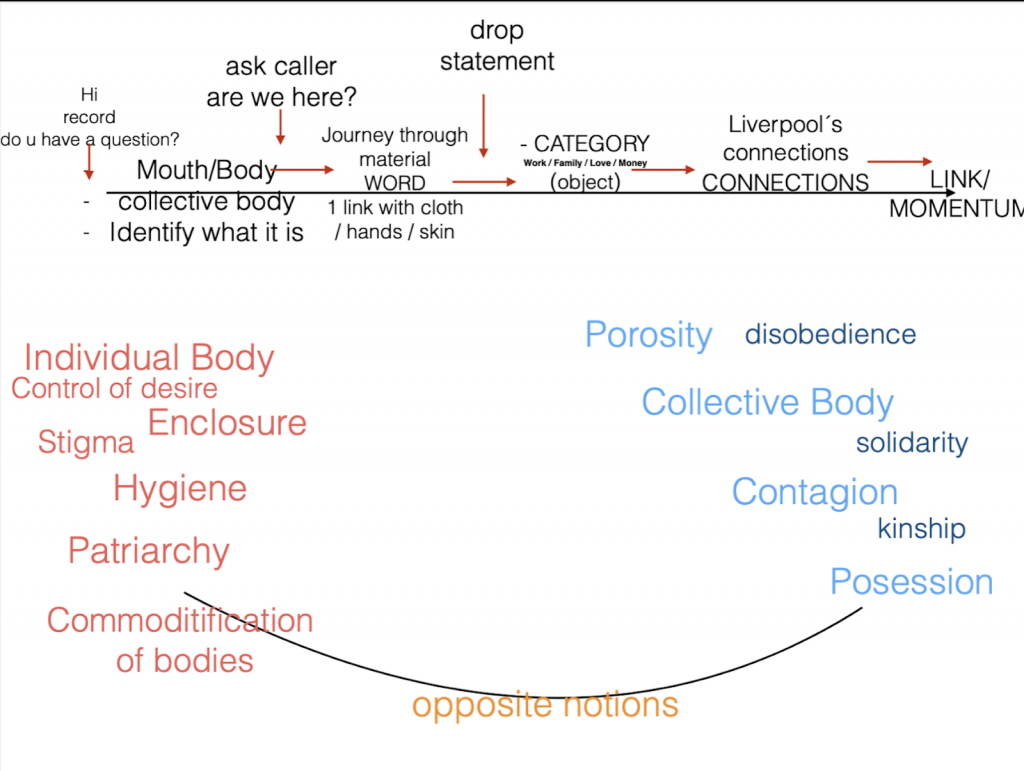

The material was built around the question: how do we relate our current situation to the colonial disease? I then identified some elements I was interested in opening up: the collective body, porosity, contagion, kinship, and possession. It worked like this: the caller would ask any question, and, based on some keys we identified, the clairvoyant would “enter” one of these nodes. They could go, for example, on the side of the collective body or of porosity, etc. He would then use the research material that we had developed. This is a script with a lot of improvisation in which the seers put into practice their mediumistic powers, guided by predetermined tools. In this sense, it also functioned as a score made for improvisation, like saying to a musician: I’m going to give you three types of notes to improvise, and whatever you find along the way is yours. Here we can see an image used in the call to these women.

This image shows the categories that we identified. Depending on the questions, the psychics placed the conversation in one of these categories. For instance, one of Carolina Cerón’s calls was about body and voice. In that case, Conway, the medium with whom Carolina spoke to twice, identified the clues and decided in which direction to move as she was inspired. In the words in blue, we can see what I was interested in opening up during conversations.

The medium identified the questions, for example, if she was asked about work, family, love, or money. As in previous projects, I recognized that many questions tend to be about these topics and are usually crossed by anxiety. Initially, the conversation is located in the immediate: the clothes you are wearing or how you wash them, your mouth, or your day at work. During the call, circuits are generated between the historical, the past, and the future intuitively, always shaped by the immediate situation and the urges uttered by the caller. Various conversations revolved around the extraction of materials and objects and their presence in museums. Trying to make the caller experience a way of critically accessing the material is complex and difficult to define; if the system opens up to other forms of exchange, it will hold some power that cannot be reduced to a formula. At its best, the medium’s exercise had a lot of power. They had some clues in their mind, but they responded with clairvoyance to what they were identifying, mixing it with the material conditions of the listener. When it worked, it generated strong connections that offered other meanings to the caller’s daily life.

The images here are screenshots of some parts of the initial score.

This image shows the nodes they had in mind at the time of the call.

The audience was invited with the following sentence: Reversal consultations can help you identify the nature of what you already ingested. Regurgitation is the way; constant rumination is a must. You have been colonized by uncountable hidden diseases. We might show you the symptoms. Pricking, a tooth, soap, ticks. Do you want to remember? Remove the center, and the universe will open for you. Clairvoyant skills to guide your way back and forth. Access what they tried to silence. Melt with the (im)pure margins. Custom-made spells harness the proximity of the Voice.

IAG: Your work has always emphasized the use of performance. Now that we’ve talked a bit about the research and the process of making the script let’s go back and talk about the need you found to work with these seers and not just performers.

LU: Tropes, figures and images traverse time, reminding us that history is neither linear nor continuous nor transmissible, and that we access it in quotations and fragments; some time ago I came across a story in Bogota of a girl whose father punished her for talking too much by cutting out her tongue. In the history of the so-called witches, for example, the question is not what the history of the witches is but what part of that history is still going through me.

I was looking for women with a talent for stories. Like the performer and the shaman, the seer prepares a way of acting. She rehearses a system, and this system comes to life. What I pointed out about ‘the continuous work of simulating reality’ worked well whenever I interacted with someone who had experience in the performative and a capacity for clairvoyance. Someone who had no problem playing with the format and who, at the same time, took its clairvoyant power seriously. It was important for me to not instrumentalize the knowledge of the clairvoyants and, to achieve this, the relationship needed to be sincere with that kind of wisdom and practice. I talked to many women in Liverpool and found different ways of relating to local knowledge and collections.

I have previously worked with local knowledge experts whose practices question modern differences between culture and nature in their making. As the work for this project involved a truly speculative conversation that would resonate with a specific research material and, at the same time, cut through the questioner (seeking how their current situation relates to colonial disease), it was clear that the answerer could not just repeat a pre-established script.

IAG: How was your experience working with Manuela Moscoso during these weird moments of the pandemic?

LU: The pandemic confronted Manuela with several challenges, some of them really strong. What impacted me the most was that she managed—throughout this demanding process—to maintain coherence between what the Biennial proposed in its contents and how we worked, especially under the limitations of the pandemic. She really applied kinship and all the other terms. She and her production and education team managed to maintain respectful working relationships with the artists all the time. When we had to transform the work along the way, it was amazing to see how she could remain caring and respectful besides being a generous listener. In my case, it would have been a safer bet to repeat a script and employ performers who were not mediums. But Manuela took a gamble and decided to go ahead with the experiment.

I am interested in questioning established hierarchies between forms of knowledge. That was an exciting challenge with Manuela, who understood it, took the plunge, and made experimentation, the body, and a flexible position prevail over the pre-established product. Manuela faced a very tough situation with a program that talked about kinship, porosity, and the body, and she could pull it off. She met all kinds of problems, which implies strength in management. She often had to stand firm in the face of different powers in the institution to protect practices of care and be consistent with the concepts proposed for The Stomach and The Port. All of that is challenging in terms of productivity and contemporary capitalism.

Una conversación entre Inés Arango Guingue y Luisa Ungar sobre A Regurgitation is a Song is a Spell (Consultations to Recreate the Colonial Disease) (2021), obra de Ungar para la Bienal de Liverpool en 2021.

Spanish version

Inés Arango Guingue: Manuela Moscoso tituló esta edición de la bienal “The Stomach and the Port”, El Estómago y el Puerto, creando una relación directa entre esta parte del cuerpo y el puerto de Liverpool. En el texto curatorial afirma que “El estómago se puede pensar como el puerto de los intestinos, un lugar donde el exterior viene a desembarcar. […] El estómago no puede ignorar estos elementos “extranjeros” y debe interactuar con ellos, ya sea preparándolos para su transición hacia las células del resto del cuerpo o decidiendo lentamente devolverlos a la boca.” Como artista comisionada para crear una proyecto de sitio específico, ¿Cómo te involucraste con este contexto?

Luisa Ungar: Cuando Manuela me invitó a formar parte de la Bienal, empezamos una conversación enriquecedora: la metáfora del estómago nos llevó a hablar de nociones como porosidad/parásitos/fluidos y, a partir de ahí, a trabajar desde el cuerpo y con el cuerpo. Me pregunté entonces por los cuerpos extraños y si éstos implicaban de alguna manera cierta resistencia a esa máquina colonial “que se lo tragaba todo”. Buscando “entrar” en esa boca del estómago, me acerqué a algunos archivos y colecciones del puerto. Poco a poco fui encontrando vasos comunicantes que me guiaban por Liverpool. Suelo trabajar así, identificando hilos que me permiten “jalar” algunos de los circuitos coloniales que nos atraviesan en el presente, siguiendo pistas como señales de orientación.

En el primer viaje de investigación, revisé archivos del Museo Marítimo de Meyerside (Meyerside Maritime Museum), algunos procedentes de las colecciones de la Escuela de Medicina Tropical de Liverpool (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine) – como otras ciudades portuarias claves durante el periodo colonial, Liverpool cuenta con centros activos de investigación de enfermedades tropicales- y otros de la Escuela de Dentistería de la ciudad (University of Liverpool Dental School) y del Museo Internacional de la Esclavitud (International Slavery Museum). También exploré el Museo del Mundo (World Museum), su espacio atiborrado de piezas de todo tipo procedentes de distintas regiones del mundo, manifiestos de poder y control, formas de sistematización y clasificación del conocimiento y la extracción.

Las pistas que surgieron en este escenario me llevaron a pensar en nociones de contagio, posesión, estigma e higiene… y a la vez en manifestaciones de “kinship” y porosidad. Surgieron elementos a manera de nodos o “claves” en los circuitos que iba identificando y que funcionaban como detonantes con los que me empecé a obsesionar, semillas que encapsulan espíritus del pasado.

Uno de estos elementos fueron los dientes. La Escuela de Dentistería de la ciudad (University of Liverpool School of Dentistry) tiene una extensa colección de dientes. Estos dientes son un “lugar” (una parte del cuerpo y una parte del mundo), donde se empieza a manifestar el dispositivo colonial: los dientes se empiezan a dañar por la importación, primero exclusiva y después masiva, de azúcar y tabaco. Y se empiezan a dañar primero los dientes de las clases altas porque son los primeros que pueden acceder a esos nuevos productos. Las primeras prótesis dentales se fabricaban con bloques macizos de marfil de hipopótamo, morsa o elefante; las siguientes fueron piezas extraídas de bocas de soldados muertos en la batalla de Waterloo o de personas sin recursos que las vendían para sobrevivir al creciente sistema: en esos dientes podemos vislumbrar tanto la agencia de las plantas extraídas de los territorios colonizados, como las prácticas sociales de segregación (de humanos y no humanos) generadas por el creciente sistema capitalista.

Para mí, localizar el sistema en el que se inscribe el objeto abre su significado y su uso en términos de posibilidades performativas. En este sistema, una cosa lleva a otra, y así surgen posibles relaciones que abren sus significados. Entender un objeto en su sistema narrativo me permite jugar con ese sistema de alguna manera. En Liverpool confluyen y se anudan dinámicas surgidas en territorios separados por enormes distancias geográficas y culturales, alimentadas por el tráfico transatlántico de personas esclavizadas. La popularización del jabón en la ciudad, por ejemplo, comenzó con la importación de aceite de palma, lo que facilitó la creación de empresas como Lever & Co, que hacia 1884 comenzó a producir en masa el jabón Sunlight, aprovechando la reciente importación del Congo de aceite de palma producido por personas esclavizadas. Con los años, la empresa de Lever se convertiría en Unilever, uno de los mayores conglomerados económicos del mundo.

Estos objetos se relacionaron con otros que fueron apareciendo en este sistema de relaciones; así surgieron la brida de regañar, o “brank”, (un objeto de tortura utilizado para herir y humillar a las mujeres cuyo discurso se consideraba ofensivo) en su intento de censurar las voces que implicaban resistencia al sistema en auge (en el International Slavery Museum), y, en otro extremo del espectro, un objeto como el “tocado usado por los curanderos naidugubele durante las consultas, Costa de Marfil”, parte de la colección africana del Museo del Mundo.

IAG: ¿Cómo se materializó esto en tu proyecto?

LU: Elaboro los guiones de mis performances en varias capas, y el “cómo” surge de la propia investigación. Revisar epistemologías que cuestionen narrativas dominantes me lleva a trabajar con las conversaciones que mantengo con las personas que conozco durante la investigación. La oralidad, la conversación y el chisme son elementos importantes en mi trabajo, me interesan los sistemas especulativos de conocimiento. Hablamos con Manuela desde el principio sobre el lugar que ocupa la conversación en mi obra y cómo se transforma en un medio de contraste que se activa a partir de los elementos que se encuentran en archivos y colecciones que sirven de pistas, como he mencionado antes. En esta constelación, y en diferentes sentidos, la boca ocupa un lugar significativo.

En Liverpool realicé tours por la ciudad y conversé con personas siguiendo los hilos que he mencionado, guiándome por el contagio y la infección. En el MFA en performance de Hope University, mantuvimos reuniones con Silvia Battista, Anna Laura Alifuoco y sus estudiantes. También conversé con el curador de la colección de objetos africanos del Museo del Mundo sobre las nociones de posesión, estigma y contagio, y con expertos de la Escuela de Medicina Tropical de Liverpool, institución pionera en los “análisis de sangre de un solo pinchazo” desarrollados para identificar las enfermedades que traían los soldados que luchaban en guerras en países tropicales. Los pinchazos, el contagio y la noción de estigma y posesión me dieron pistas para entender el “cómo” del proyecto. Empecé a visitar las sesiones de teatro comunitario de Playhouse/Life Rooms para identificar posibles mujeres no actores con las que pudiéramos trabajar. Trabajando en esto llega la pandemia. Me toca entonces salir rápidamente de la ciudad y volar a Bogotá.

IAG: La pandemia interrumpió bruscamente tu investigación sobre el terreno. ¿Cómo evolucionó este proyecto mientras ya no estabas en Liverpool?

LU: Desde la distancia y el encierro de cada uno de nosotros, nos reunimos periódicamente con el equipo de producción y educación de la Bienal y seguimos las conversaciones con Manuela. Durante los primeros meses, creímos que sería posible hacer el proyecto tal y como lo habíamos pensado y que sólo tendríamos que hacer algunas variaciones. Iba a ser una performance en el espacio público activada por la intersección entre los objetos, las narrativas que circulaban por la ciudad y las respuestas de las personas que entraban en contacto con estas historias mezcladas. Se presentaría a lo largo de la Bienal como una visita guiada periódica, casi diaria, y tendría lugar en el centro de la ciudad: desde el Museo del Mundo, caminaríamos hasta St George’s Hall. Desde mi cuarto en Bogotá, trabajar en la acción en el espacio público de Liverpool tuvo una especie de efecto liberador. Al mismo tiempo, el equipo educativo estaba ansioso por salir y probar los guiones como excusa para salir de sus casas.

A medida que avanzaba la pandemia, tuvimos que modificar las condiciones de la obra: constantemente aparecían nuevas normativas que implicaban cambios en el número de personas que podían estar en grupo en espacios públicos y privados y en el número de grupos posibles. Tuvimos que ir modificando los tamaños, el número de espectadores y el sistema de amplificación de la voz en las locaciones, buscando mecanismos que no requirieran proximidad física entre el público y las performers y reducir así la posibilidad de contagio. Varias veces tuvimos que averiguar distintos sistemas de amplificación del sonido. Cada vez que se reducía el tamaño permitido de los grupos de público, también aumentaba la distancia requerida entre cada “clusters”. Esto supuso algunos retos apasionantes para la obra; así, las nociones de porosidad, contagio y parentesco adquirieron otras dimensiones. Hasta que, en un momento dado, tuvimos que aceptar que no habría programa público en la Bienal de Liverpool.

Estábamos revisando opciones para poder hacer alguna versión de la pieza, como convertirla en una pieza solamente en audio, cuando me di cuenta de que eran las conversaciones virtuales la clave de la obra: a través de las conversaciones eran posibles otras formas de contagio. La pandemia nos volvió a la intimidad del espacio físico mientras nos exponía a la sobre exposición de la virtualidad. Las conversaciones sin imagen respondían también a este asunto. Entonces empecé a revisar la idea del call center. Me gustaba jugar con referencias tomadas de la cultura de los call centers, el trabajo a distancia y las implicaciones que esas modalidades de trabajo tienen, incluso para el campo del arte. Además de la noción de contagio, para entonces, la boca y la voz ya eran elementos esenciales del proyecto, tanto de la investigación como de la situación que estábamos viviendo.

IAG: El trabajo con videntes fue una parte esencial de esta obra. Hablemos más sobre cómo el trabajo con estas personas se conectaba con la investigación in situ que hiciste.

LU: Claro, el trabajo con videntes tuvo que ver con varios factores que se dieron en el proceso, tanto desde la investigación, como por el cambio en las condiciones de producción que generó la pandemia, y que resultarían en conexiones que respondían de forma increíble a las claves encontradas por el camino.

Por un lado, la figura del clarividente nos permitió crear la conexión entre nuestra situación actual y la enfermedad colonial. ¿Qué papel juega la herramienta narrativa en todo esto? ¿Podríamos crear un guión que respondiera a nuestras vidas actuales y abordara algunos de los elementos presentes en la investigación? Trabajar con clarividentes me permitió comunicar la experiencia de que la transmisibilidad de la historia no es posible, que sólo podemos arrancarla de su contexto, fragmentada y destruida, desmenuzada y descompuesta. Ellas surgieron como una clave que podía vincular las voces de distintas partes del mundo con las locales; su trabajo permitía la porosidad, y con ellos la persona que llamaba podía interactuar con algunos de los materiales encontrados y, al mismo tiempo, reconocer la presencia y la agencia de bacterias, espíritus, animales, divinidades, virus, etc.

Por otro lado, el trabajo de investigación en Liverpool hablaba de higiene, contagio, chisme y persecución de mujeres, y también se refería a la presencia de organizaciones de mujeres en Liverpool. Es imposible pasar revista al dispositivo colonial en la zona sin oír hablar de la presencia de las formas de segregación que les señalé al principio. Cuando el aparato colonial empieza a funcionar, hay presencias que, desde “dentro del estómago”, son un obstáculo y una amenaza para el creciente sistema capitalista.

Siguiendo la perspectiva de Silvia Federici, me refiero a los cientos de miles de mujeres asesinadas en el marco de la persecución de las supuestas “brujas”. En Liverpool, además de la brida de regañar (o “brank”), un instrumento de castigo utilizado para demostrar que estas mujeres estaban poseídas era el Ducking Stool, que consistía en hundirlas atadas a sillas en el agua de los canales de la ciudad para que confesaran (uno de esos lugares estaba junto a St Patrick’s Cross). Otra forma de maltrato eran los pinchazos, con los que se intentaba comprobar si salían gotas de sangre de sus cuerpos; también se buscaban supuestas “marcas del diablo”: rastros en sus pieles que probaran su posesión. En el siglo XX se demostraría que esas marcas eran granulomas resultantes de la picadura de garrapatas, otro agente procedente de América, que picaba sobre todo a los trabajadores de granjas y huertos y cuyas bacterias generan la enfermedad de Lyme (Borrelia burgdorferi). Autores como M. Drymon han estudiado cómo afecciones asociadas a la brujería seguían apareciendo en los mismos lugares en los que podría haberse producido esta enfermedad. También habían aparecido figuras relevantes en la investigación, como Mary Wilkinson, quien ocupa un lugar en el Liverpool de finales del siglo XIX, al demostrar que el cólera no se manifestaba en las reuniones de lavanderas locales. El trabajo resonó entonces en sus diversas conexiones: formas de conocimiento y prácticas que han sido estigmatizadas y marginadas por el mundo moderno-capitalista, y lo que diversos materiales de la ciudad podrían decir sobre contaminaciones potenciales entre regímenes de conocimiento, revisando formas de privación de las voces de las mujeres en conexión con la historia local.

IAG: Los hilos que querías jalar eran, de cierta manera, bastante amplios. ¿Cómo empezó a tomar forma el proyecto después de toda esta investigación?

LU: La decisión de trabajar con llamadas telefónicas dio lugar a la pieza titulada Una regurgitación es una canción es un conjuro (Consultas para recrear la enfermedad colonial), en la que trabajamos con un grupo de clarividentes en torno a diversos tipos de material procedente de colecciones y archivos de la ciudad. Las expertas estaban a disposición del público para responder a sus preguntas a través de llamadas telefónicas. Invitamos a los que llamaban a “hacer una pregunta, compartir una preocupación o una urgencia”. Podía llamar cualquier persona de cualquier parte del mundo.

Cuando decidí trabajar con clarividentes que se identificaban como mujeres, iniciamos el proceso del casting para encontrarlas. Quizá esto fue lo que más me gustó de todo el proceso. Con ellas, puse en juego los elementos críticos del guión; a partir del material de investigación y en función de las habilidades, experiencia en el contexto y metodologías de cada una, se desarrolló la consulta. La conversación ponía en relación la situación actual del consultante con el sistema de lectura de la vidente y los elementos de las colecciones. No inventamos el material. Todo formaba parte de la investigación. Para mí, llamar la atención sobre el trabajo continuo de simulación de la realidad es esencial.

El material se construyó en torno a la pregunta: ¿cómo relacionamos nuestra situación actual con la enfermedad colonial? Entonces identifiqué algunos elementos que me interesaba abrir: el cuerpo colectivo, la porosidad, el contagio, el parentesco y la posesión. Funcionaba así: la persona que llamaba hacía una pregunta cualquiera y, a partir de unas claves que identificamos, la clarividente “entraba” en uno de esos nodos. Podían ir, por ejemplo, por el lado del cuerpo colectivo o de la porosidad, etc. A continuación, la clarividente utilizaría el material de investigación que habíamos elaborado. Se trataba de un guión con improvisación en el que las videntes ponían en práctica sus poderes mediúmnicos, guiados por herramientas predeterminadas. En este sentido, también funcionaba como una partitura hecha para la improvisación, como decirle a un músico: Te voy a dar tres tipos de notas para que improvises, y lo que encuentres por el camino es tuyo. En la imagen 3 se puede ver una parte del guión utilizado en las llamadas.

Esa imagen muestra las categorías que identificamos. Dependiendo de las preguntas, las videntes situaron la conversación en una de estas categorías. Por ejemplo, una de las llamadas de Carolina Cerón trataba sobre el cuerpo y la voz. En ese caso, Conway, la médium con la que Carolina habló dos veces, identificó las pistas y decidió en qué dirección moverse según su lectura. En las palabras en azul podemos ver lo que me interesaba abrir en la conversación.

La clarividente identificaba las preguntas en categorías, como el trabajo, la familia, el amor o el dinero. Como en proyectos anteriores, reconocí que muchas preguntas suelen versar sobre estos temas y suelen estar atravesadas por la ansiedad. Inicialmente, la conversación se situaba aparentemente en lo inmediato: la ropa que quien llamaba llevaba puesta o cómo la lavaba, cómo estaba su boca o qué tal había sido el día de trabajo. Durante la llamada, se generaban circuitos entre lo histórico, el pasado y el futuro de forma intuitiva, siempre moldeados por la situación inmediata y las urgencias expresadas por quien llamaba. Varias conversaciones giraron en torno a la extracción y los objetos de los museos de la ciudad, y cómo fueron robados de sus lugares de origen.

Intentar que quien llama experimente una forma de acceder al material de forma crítica es complejo y difícil de definir; si el sistema realmente se abre a otras formas de intercambio tendrá una potencia que no es reducible a una fórmula. Porque cuando funcionaba, la lectura de las médium tenía mucho poder. Ellas tenían en su mente algunas claves pero realmente respondían con clarividencia con lo que iban identificando, mezclándolo con las condiciones materiales del oyente. Cuando funcionaba generaba unas conexiones fuertes que ofrecían otros sentidos a la cotidianidad de la persona que llamaba. La imagen 4 es un pantallazo de algunas partes del guión inicial y muestra algunos nodos que ellas debían tener en mente en el momento de la llamada.

La invitación a los públicos a participar de las llamadas fue la siguiente: Estas consultas inversas pueden ayudarte a identificar la naturaleza de lo que has ingerido. La regurgitación es el camino; la rumiación constante es indispensable. Usted ha sido colonizadx por incontables enfermedades ocultas. Podemos mostrarte los síntomas. Pinchazos, un diente, jabón, garrapatas. ¿Quieres recordar? Remueve el centro, y el universo se abrirá para ti. Habilidades clarividentes para guiar tu camino de ida y vuelta. Accede a lo que intentaron silenciar. Fúndete con los márgenes (im)puros. Conjuros personalizados que aprovechan la proximidad de la Voz.

IAG: Tu trabajo siempre ha hecho énfasis en el uso del performance. Ahora que ya hablamos un poco sobre la investigación y el proceso de hacer el guión, devolvámonos un poco y hablemos sobre la necesidad que encontraste de trabajar con estas videntes y no solo con performers.

LU: Los tropos, figuras e imágenes atraviesan el tiempo, recordándonos que la historia no es lineal ni continua ni transmisible, sino que accedemos a ella en citas y fragmentos. Hace un tiempo conocí en Bogotá la historia de una niña a la que su padre castigó cortándole la lengua por hablar demasiado. En la historia de las así llamadas brujas, por ejemplo, la cuestión no es cuál es la historia de las brujas, sino qué parte de esa historia sigue atravesándome.

Buscaba mujeres con talento para las historias. Al igual que la intérprete o el chamán, la vidente prepara una forma de actuar. Ensaya un sistema, y este sistema cobra vida. Lo que señalé sobre “el trabajo continuo de simulación de la realidad” funcionó bien siempre que me uní a alguien que tuviera experiencia en lo performativo y capacidad de clarividencia. Alguien que no tuviera problemas en jugar con el formato y que, al mismo tiempo, se tomara en serio su poder de medium. Para mí era importante no instrumentalizar el conocimiento de las clarividentes y, para lograrlo, la relación debía ser sincera con ese tipo de sabiduría y práctica. Hablé con diferentes mujeres de Liverpool y encontré distintas formas de relacionarme con los conocimientos y las colecciones locales.

Anteriormente he trabajado con expertos y expertas en conocimientos locales cuyas prácticas cuestionan las diferencias modernas entre cultura y naturaleza. Como el trabajo para este proyecto implicaba una conversación verdaderamente especulativa que resonara con el material de investigación y, al mismo tiempo, atravesara a quien preguntaba, (buscando cómo se relaciona su situación actual con la enfermedad colonial), estaba claro que quien contestaba no podía limitarse a repetir un guión preestablecido.

IAG: ¿Cómo fue tu experiencia trabajando con Manuela Moscoso durante estos extraños momentos de la pandemia?

LU: La pandemia enfrentó a Manuela con varios desafíos, algunos de ellos realmente fuertes. Lo que más me impactó fue que ella logró —a lo largo de este exigente proceso— mantener la coherencia entre lo que la Bienal proponía en sus contenidos y cómo trabajábamos, especialmente bajo las limitaciones de la pandemia. Realmente aplicó parentesco y todos los demás términos. Ella y su equipo de producción y educación lograron mantener relaciones de trabajo respetuosas con los artistas todo el tiempo. Cuando tuvimos que transformar el trabajo en el camino, fue increíble ver cómo ella podía seguir siendo cariñosa y respetuosa además de ser una oyente generosa. En mi caso, hubiera sido una apuesta más segura repetir un guión y emplear a actores que no fueran médiums. Pero Manuela se arriesgó y decidió seguir adelante con el experimento.

Me interesa cuestionar las jerarquías establecidas entre diferentes formas de conocimiento. Ese fue un reto apasionante con Manuela, que lo entendió, dio el paso, e hizo prevalecer la experimentación, el cuerpo y una postura flexible sobre el producto preestablecido. Manuela enfrentó una situación muy difícil con un programa que hablaba de parentesco, porosidad y cuerpo, y lo pudo sacar adelante. Enfrentó todo tipo de problemas, lo que implica solidez en la gestión. Muchas veces tuvo que mantenerse firme frente a los diferentes poderes de la institución para proteger las prácticas de cuidado y ser consecuente con los conceptos propuestos para El Estómago y El Puerto. Todo eso es un desafío en términos de productividad y capitalismo contemporáneo.

Luisa Ungar lives in Bogotá, Colombia, and Berlin, Germany. Ungar´s multidisciplinary practice explores how social norms are constructed and institutionalized through language. She is interested in mechanisms that question ways in which local history is constructed, using didactic strategies that trace colonial structures implicit in our ways of learning, communicating and speaking. She looks for threads on animality and the non-human which shape our behavior, and her performances are often built on conversations from the local environment and interweave micro-stories with seemingly disjointed historical narratives and archaeological remains in order to build new layers of meaning. Recent exhibitions and performances include Liverpool Biennial (2021); MKHA, Belgium (2018); Rijksmuseum, the Netherlands (2017); Ar/Ge Kunst, Italy (2017); and BienalSur, Argentina (2017). In 2019 she curated the performance and education program for Colombia´s Biennial 45SNA.