Installation view of Animated Drawings for a Glacier, SAIC Galleries. Photo by Tony Favarula.

Change across Deep Time in the Work of Meredith Leich

By Sophie Buchmueller

I first became acquainted with artist Meredith Leich when working as a curatorial assistant for the exhibition Earthly Observatory at SAIC Galleries. On view in fall of 2021, the group show curated by SAIC faculty members Andrew Yang and Giovanni Aloi sought to interrogate how we—as humans—navigate, comprehend, and represent our complex planetary entanglements. Assembling objects by a range of practitioners working in and across the fine arts and natural sciences, the exhibition explored how various modes of observation and sensory perception inform methods of relating to the natural world. Occupying a darkened space at the west end of the subterranean gallery, Leich’s multimedia installation, Animated Drawings of a Glacier (2018–2021), was composed of two videos projected on opposing sides of the room on white fabric screens suspended from the ceiling. Featuring glacial landscapes at the eastern and western extremes of North America—erratic boulders along the shore of Cuttyhunk Island in Massachusetts and icebergs calved from the Kennicott Glacier in Alaska—the videos document the artist’s ephemeral interventions at each site. The videos are the result of an iterative process, in which Leich drafted charcoal sketches in response to her surroundings, photographing the drawing between each mark to create a stop motion animation that she projected back onto the geologic forms. In their display at SAIC Galleries, documentation of the two site-specific encounters seeped into each other. With overlapping soundscapes of tinkling ice melt and softly lapping waves and an aura of soft blue light enveloping the room, the components blend to form an immersive environment, the two coasts entering into dialogue with each other for the viewer.

Earthly Observatory closed in December 2021, and yet months later Leich’s installation continues to haunt me. This is in part because I have a personal connection to one of the locations—several summers ago I spent an idyllic week on Cuttyhunk (though at that point I was unaware of its geologic significance). In addition to recalling fond vacation memories, however, I believe what draws me to Animated Drawings for a Glacier is how the artwork subtly weaves together massive spatial expanses and deep flows of time. The installation manages to crystallize processes occurring on diffused, planetary scales into a human-scaled aesthetic experience, linking the universal to the individual without being overly simplistic or reductive. This profile, developed from a conversation I had with Leich in January 2022, seeks to paint a broader picture of her artistic practice by detailing a few of her research-informed projects as well as discussing her general approach to addressing anthropogenic climate change in her work.

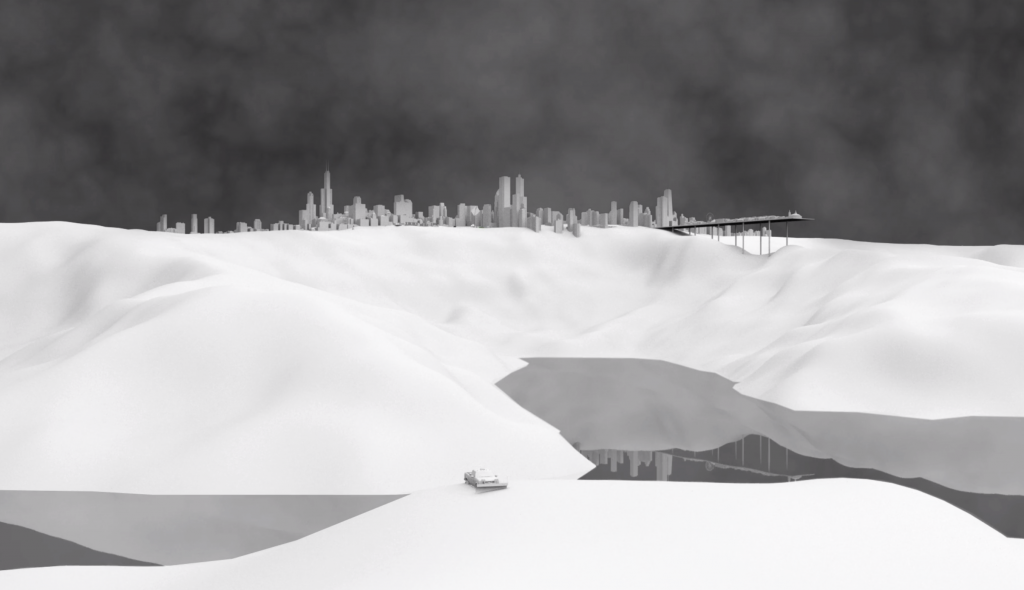

Often Leich’s undertakings unfold over a period of years; an initial spark of curiosity blossoms into a sustained line of inquiry. Because of how these explorations gradually unfurl, one project bleeds into the next, with ideas crosspollinating and reinforcing each other. Animated Drawings, for instance, emerged out of Scaling Quelccaya, a multi-year project Leich created with glaciologist Dr. Andrew Malone while they were both in graduate school. Formally collaborating for a year with support from an Art Science Culture Initiative Grant from the University of Chicago, they worked off Malone’s PhD research on Quelccaya in Peru, the world’s largest (yet rapidly melting) tropical glacier. To assess changes in the ice from year to year, Malone utilized satellite imagery, gathering information based on how light rays bounced off various materials. Leich transformed the aerial photos of the retreating formation into a three-dimensional model, which she then merged with a three-dimensional model of Chicago. By transposing the sites over one another, she deployed the city’s iconic skyline as “a surreal measuring stick” through which to visualize the ice cap’s shrinking mass and the world-altering ramifications of global warming. Leich and Malone were invited to speak at multiple venues about their collaboration and their film, Scaling Quelccaya (2017), was shown at festivals in the United States and abroad.

Film still from Scaling Quelccaya. Courtesy of the artist.

Following experience of working with satellite imagery of glaciers, Leich was determined to visit one in person. In 2017, she was a resident at the Wrangell Mountain Center in the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve in Alaska, where her ideas for Animated Drawings began to take shape. “Encountering an actual glacier was so powerful, it felt so strangely alive,” she recalled. “After all of these computer-based images, walking and moving and feeling the light bouncing off the ice and feeling both warm and very cold… I felt like I wanted to revisit the idea of animation and glaciers, but through a much more direct and in a much more responsive way.” Back in the Lower 48 after the residency, she experimented with creating charcoal line drawings in response to New England’s glacial landscapes. She returned to Alaska the next summer, developing sketches and animations based on her observations on the Root and Kennicott Glaciers. The trip culminated with two night hikes with groups of roughly a dozen people. Out on the ice, Leich set up a battery-powered projector and played the animation onto the glacier’s surface, capturing the scene on video. She explained to me that the projection was an homage to the glacier, the animation capturing their rolling forms, layered patterns, and creeping movements. It took several more years, however, for the work to evolve into the display in Earthly Observatory. While in her home state of Massachusetts, helping out at the Cuttyhunk Island Artists’ Residency, Leich learned that Cuttyhunk was once the southernmost tip of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which blanketed northern North America 10,000 years ago, and the gigantic rocks dotting the coastline were deposited by the retreating moraine. With this realization, the pairing came into focus: two sites with parallel geologic histories separated by thousands of miles. The thirty years of melting she had visualized with Malone stretched into an exploration of millennia of change. Kennicott and Cuttyhunk represent two chapters of the same story etched into the geologic record, the narrative thread made legible through the artist’s astute pairing.

Animated Drawings for a Glacier, documentation showing Leich projecting onto the Root Glacier. Photo by Maya Heubner.

When I spoke with Leich this past winter, she was toying with a new idea that had grown out of Animated Drawings. She joined our Zoom call from Skagaströnd in northwestern Iceland, where she was finishing up a month-long residency. There, she had been researching the ocean and wind currents that produce a habitable environment on the subarctic island. As the planet warms and ice caps melt at an increasingly rapid rate, however, these weather patterns will shift or possibly even collapse, wreaking havoc on a worldwide scale.1 Fascinated by how these invisible systems play a determining role in our lives, Leich began to paint their paths as represented in scientific diagrams. After converting the watercolor paintings into animations, she then composited them with footage of birds into an experimental video collage that was projected on an old boat propeller abandoned on the shore. Much like Animated Drawings, this site-specific intervention, entitled At the Currents’ Edge (2022), translates something huge, dispersed, and intangible in its entirety (what environmental philosopher Timothy Morton would call a hyperobject) into a personal and immediate experience.2 Crucially, the work does not seek to fully encapsulate or make sense of these atmospheric systems, rather Leich offers an open-ended meditation that teases parts of an ultimately incomprehensible whole. She emphasized that this recent exploration of currents is still in its early stages, and she hopes to collaborate with another scientist to grow the project over the next few years.

At the Current’s Edge, documentation of site-specific screening on found propellor, Skagaströnd, Iceland. Courtesy of the artist.

An aspect of Leich’s practice that I find especially compelling is its lightness. Her interventions in the landscape are understated and fleeting—a brief twilight performance for a few lucky guests—that live on only in their documentation. Her inobtrusive approach stands in sharp relief to many of the canonical works from the Land Art movement of the 1960s and 1970s.3 For example, Michael Heizer’s well-known earthwork in the Nevada desert, Double Negative (1969), in which the artist carved two trenches (each thirty feet long and fifty feet deep) into opposite sides of a mesa, is a radically different gesture than Leich’s endeavors. Using heavy machinery to displace 240,000 tons of sandstone, Heizer scarred the land, his actions an expression of masculine force and attempted domination over nature. Leich’s delicate interventions, by contrast, adhere to the backcountry hiking mantra of “leave no trace;” her projections dance across surfaces without impressing permanent marks. In this way, her practice is perhaps more similar to that of sculptor and environmentalist Andy Goldsworthy, whom she cites as an inspiration. “I really love his more ephemeral work, like the beautiful stuff he does with leaves and with icicles,” she reflected. “He’s clearly observing his environment then making these subtle alterations… He’s very time focused and environment focused.” Like Goldsworthy, Leich incorporates observation-driven acts into her practice, but I see their practices diverging in how Leich combines this site-responsiveness with a conceptual framework rooted in scientific research about the natural world.

Finally, I want to spend a moment on Leich’s reasons for engaging climate change as a subject matter. As we talked, she shared that although she admires artists working in an activist bent who raise awareness about pressing issues and spur viewers into action through their work, her own practice derives from more private motivations. She explained:

I’ve had for a long time this sort of foreboding sense that the life I’ve been taught to live will not necessarily be possible within a certain number of decades, because things are going to change so much. I’m scared of extreme weather, I’m afraid of crop shortages, I’m afraid of social unrest that comes about from this—I think it’s already being stoked in various ways. The particular angle that I seem to take for climate change is to try to transform my fear into interest. And it’s not exactly like, here’s the solution as much as like, here’s a way we can stay with this theme without shutting it out. Here’s a way to stay present, to get curious, to find meaning. Not to find meaning in disaster, but to find meaning in the world such that we can stay invested enough to be involved in some way. I’m trying to transform my fear into curiosity a lot of the time, and then trying to invite other people to come along.

Meredith Leich

Leich’s perspective made me think of the writings of Donna J. Haraway, an ecofeminist thinker whose work has been foundational to my own development as a scholar.4 In a recent book, Haraway proposes alternative methods for relating to the world and its diverse, multispecies inhabitants in the face of pressing environmental disasters.5 She calls for “staying with the trouble,” which means remaining present and committed to our earth-bound entanglements rather than either getting swept up in fears and hopes for the future or retreating into reminiscing about the past.6 Along related lines, I understand Leich’s drive to find meaning amidst unsettling change and precarity as a powerful attempt to reckon with—in the here and now—some of the planet’s many interrelated ecological crises. By rooting her work in physical sites and the existential threats they are facing, she stays attuned to the stakes at hand.

Even though Leich may not present herself as an activist necessarily, her approach to working with climate change emphasizes the importance of pursuing sustained, research-driven engagement with a topic that can often feel overwhelming in its seriousness and impenetrable in its vastness. From Scaling Quelccaya to Animated Drawings for a Glacier to At the Currents’ Edge, the artist translates scientific knowledge into poetic speculations that welcome non-specialist audiences into the fold. While it may feel tempting to willfully ignore climate change out of fear or uncertainty, the issue demands our continued attention. As she said at one point in our call, “Let’s stay with this topic. Let’s not shut it out because it’s too frightening.”

For more on Meredith Leich’s practice, her personal website is http://meredithleich.com.

Notes

- In 2021, climate scientists warned that the Gulf Stream is at risk of shutting down at an unknown point in the future, an event which would have calamitous repercussions on a planetary scale. See Damian Carrington, “Climate Crisis: Scientists spot warning sign of Gulf Stream Collapse,” The Guardian, August 5, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/aug/05/

climate-crisis-scientists-spot-warning-signs-of-gulf-stream-collapse. - “Massively distributed in time and space relative to humans,” Morton writes, hyperobjects become visible in their local manifestations and in relation to other entities but can never be seen or touched as discrete things. Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 1.

- Although I am leaning on a persistent stereotype of land artists as rugged, arrogant outdoorsmen with little regard for the natural world, I acknowledge that scholars in recent years have attempted to amend the historical record by focusing on Land Art’s overlooked nonwhite and nonmale figures. An example of this revisionist effort can be seen in MOCA’s 2012 exhibition The Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974 curated by Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon. The show included pieces by more than 80 artists working around the globe, capturing the movement’s heterogeneity. Similarly, a 2018 article addresses the dominant archetype within Land Art along with recent efforts to challenge it. See Megan O’Grady, “Women Land Artists Get Their Day in the Museum,” The New York Times Style Magazine, November 21, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/21/t-magazine/female-land-artists.html.

- Working on this profile, I initially hoped to avoid mentioning Haraway, self-conscious of the fact that she makes an appearance in most of my writing. When I mentioned the connection I noticed between Leich’s practice and Haraway’s theories, however, Leich shared that she, too, had found Haraway instrumental to her thinking in graduate school.

- Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Haraway, 10.

Sophie Buchmueller is a Chicago-based arts worker with experience in curation, collections management, and museum education. Currently, she is the Registrar at Corbett vs. Dempsey. She is driven by the potential of contemporary art to serve as a framework for knowing and understanding the world—not just as a reflection of reality, but as a mode of active engagement with our often-precarious surroundings. She holds a BA in American Studies and French from Carleton College (2016) and MAs in Art History and Arts Administration & Policy from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2022).