The Contemporary Baroque

2006

March 7 – March 30

Gallery X

Curator

Jason Foumberg

Contributing Artists

Brett Balogh, Gillian Collyer, Laura Emelianoff, Israels Etxatxu, Thomas Gokey, Jessica Hargreaves, Alessandro Keegan, Victor Maldonado, Armita Raafat, Molly Schafer

Exhibition Statement as Preserved in the SUGS/SITE Archives:

Opulent and grandiose, hyper-sensual and conspicuously pleasurable – the age of the Contemporary Baroque is upon us! This exhibition redefines and updates a historic style trhough a contemporary sensibility. Experience the ecstasy and rapture of over-stimulation via modern technologies and psychologies of the creative process.

Programs

March 7, 4:00 – 6:00 PM

Gallery X

I Heart…

April 29, 2006, 8PM – 12AM

Mercury Cafe, 1505 W Chicago Ave

Program statement from the SUGs/SITE archive:

“A benefit show by the Heartbeat SWAP collective to raise money for 826CHI. There will be an auction for art and sale of crafts. Free food and drinks. Musical Performances include: Melodic Scribes, Animate Objects, Jetstream, Frequency Below, DJ Librarian and more. Sound provided by Maxium Strength Sound System.”

Exhibition Material

Contemporary Baroque Exhibition Catalogue

Curated by Jason Foumberg

Catalogue by Ryan Swanson

The Contemporary Baroque

by Jason Foumberg

The Baroque as an artistic style emerged in seventeenth-century Italy, the Seicento. During this time the Roman Catholic Church was facing threats to its dominance from reformed Christian sects as well as the increasing popularity of secular humanism. In response, the Church employed artists to create sensually seductive art and architecture in order to win back the masses.

Today, artists no longer receive support from a patron as powerfulas the papacy, and art today does not serve the same interests as it did several hundred years ago. Yet, we are seeing a resurgence of art that maintains and affirms the stylistic tenets of the Baroque age. The reason for this is not that the past is somehow better or more profound than the present, but rather that the artistic methods of the past provide a useful tool to regain what has been lost in contemporary art, namely the unification of traditional artistic mediums with social power and cultural agency. The Seicento Baroque serves as a precedent for our time, showing that art need not prove its autonomy in order to confirm its worth. This is not to say that the linking of the contemporary with the Baroque is a deliberate anachronism. Rather, artists today are looking backwards in order to comment on the possibilities of the present. The qualities of the Baroque can help to reclaim art’s place within a wider social arena.

What is Baroque? The term will here serve as an adjective rather than denote a strict style. It is a point of reference, a quality of art making, and a way of living in the world. The Baroque strives for the decadent, the over-emphatic, the hyper sensual, and the dramatic; and it is a display of over-whelming opulence and grandeur. The Baroque can be deliberately irrational, contradictory, and morally depraved and yet remain conspicuously pleasurable. It is sometimes decorative and fashionable, and other times allegorical and figurative, but it consistently caters to an aggravated stimulation of the senses.

Is our art merely a reflection of the neo-Baroque age? Do the institutional power relations of the Baroque provide an insightful commentary for our own society? And can the employment of the Baroque idiom be used to provole viewers to question the complacent acceptance of these power relations? Or is the Baroque anti political, catering solely to affect and imagination? Whereas the historical Baroque may have sought to streamline the message of art in the service of a dominant ideology, the contemporary Baroque accepts that art can be critical and accepting of our current condition. Contemporary art has been granted the right to be ambivalent, but has it lost its power to speak to the masses because of this? This exhibition highlights the possibility for contrasting viewpoints, and it is hoped that these differing takes on the uses of the Baroque can help us understand the role of art in relation to todays cultural and political mores.

What differentiates this exhibition from other recent explorations of the contemporary Baroque is its focus on an adherence to tradition. It is entirely possible for the Baroque idiom to be translated into campy theatre and haute couture fashion design as Stephen Calloway shows in Baroque Baroque, his survey of twentieth century excess and decadence in visual culture. But the aim of the exhibition The Contemporary Baroque is to first and foremost take issue with traditional artistic ideas and forms as seen through a contemporary sensibility, not the other way around. New artistic technologies can be used to transform the literal ideals of the Baroque through the use of newly available media (see entries on Thomas Gokey and Brett Balogh). Likewise, new conceptual technologies can also be enacted to transform tradition, such as institutional critique (Armita Raafat) and the reintroduction of figuration into Minimalist aesthetics (Molly Schafer). Victor Maldonado and Israels Exatxu take issue with the Mexican Baroque heritage by exploring what happens when a hybrid style crosses yet another border. Such tensions about the concept of a universal identity are investigated in a variety of ways, either through private narratives Jessica Hargreaves) or collective emotive responses to the abstract (Laura Emelianoff) and the surreal (Alessandro Keegan, Gillian Collyer). Keegan and Collyer provide viewers with access to a private expression of surreal psychologies as well as collective human fears and desires. The introduction of the ambiguous into the Baroque language may prove more insightful to contemporary viewers than the public and all-encompassing values envisioned by the Seicento artists.

The conceptual appropriation and manipulation of the past can speak more about social, political, and otherwise human values instead of the strictly inward -looking ideals of aesthetic concern. Film, fashion, and mass produced commodities are excluded from this exhibition in the service of focusing in on a particular strain of the contemporary Baroque, namely the subversion and extension of tradition using its own devices. The art in this exhibition is indebted to the avant-garde ideals of High Modernism, but only to move outside of that sphere of hermeticism. Instead, formal concerns act in the service of the political and the social.

Rather than promoting the unfettered excesses of our culture, contemporary Baroque art can be critical of social, polítical, and emotional values. Seen through a contemporary lens, the flamboyancy of Baroque culture appears more sober than it did four centuries ago. The result is an art that looks somewhat gritty and is gothic in its worldview. We no longer seem to be interested in the transcendence of the earthbound and deliverance through beauty. Rather, the very humanness that we sought to escape is made beautiful itself as if to say that what was overlooked out of fear of the unknown may actually hold the porential for change.

The main tenets of a Baroque vision are the display and reception of pleasure. Seicento culture and capitalist culture share a love of display and the search for satisfaction. But whereas in capitalist culture, display is associated with status tied to the commodity, in the Seicento display was a means of depicting power tied to religion. While the act of conspicuous display in both societies has been termed superficial, I would argue the opposite. The objects of both societis are a direct materialization of deeply rooted desires.

The main difference between our capitalist culture and Seicento culture is the social function of art. During the Seicento art was made to be rapturously received and power was reinforced through artistic media, whereas today art is also made to be received but turns into an instant commodity with a market-imposed, built-in obsolescence. Contemporary art still reinforces power relations but does so only for those who care to play that game. In other words, it serves no purpose for the masses (who take little delight in it). One of the major questions that this exhibition asks is, can a resurgence of the Baroque provide the means for an art that is socially significant while remaining unabashedly pleasurable?

The Baroque is a movement away from the ideals of classical antiquity. The term movement is here highlighted because its importance is three-fold. First, artists using a Baroque method are moving in response to a previous conception of forms and ideas (i.e., classical beauty). In this way it is also a movement into the world at large, and away from the hermeticism of art as an autonomous object. Second, Baroque art contains an inherent movement within itself. The term Baroque originally indicated and described an imbalance in scale within a single work of art. (“This style in decorations got the epithet of Bar roque [sic] taste, derived from a word signifying pearls and teeth of unequal size,” writes Winkelmann in 1765. Although Winkelmann is not an authority on the Baroque, and his definition does nor refer to an artistic style, it is interesting to consider this quote because it is the first recorded use of the term Baroque. Pearls and teeth are an interesting pair of objects to consider in the terms of the Baroque, given the pearl’s obvious qualities of preciousness and so called “good taste” of its beholder, and the latter’s physical and metaphoric relationship to pearls, as well as the fact that when teeth are seen extant from their gums they can invoke all sorts of psychological associations and grotesqueries – which is one of the main tools of the Baroque. It is curious that “pearls and teeth of unequal size” signify opposite extremes of taste, yet both can be termed Baroque according to this original definition. This highlights the Baroque’s disparity of cultural and moral values, whether intentional or not. But I digress). Finally (and somewhat related to the Baroque work of art’s interior movement), a Baroque work of art entails the physical or intellectual movement of its spectator who cannot comprehend the whole work of art fully from one angle or mindset. The work of art may be obscured by its own means and forms (it is anamorphic), and causes the viewer’s eye to shift, or allows for a shifting of the viewer’s mindset.

There are several main features of Seicento Baroque culture: the conspicuous display of artistic skill; growing tensions between religious faith and secularism; and art in the service of a social good (“good” can be understood in the terms of both moralism and commodification). Each of these arenas articulates a relationship between parts. There is movement, tension, and conflict. Intense exchanges between people and objects, or individuals and their society, are the preconditions for cultural development, which the visual arts thoroughly reflect.

One of the products of Seicento tensions was the rise of individualism and secularism. These were manifested through a conflict between the individual and the institution, a problem that artists are still dealing with today. The formation of identity in relation to larger structures of institutionalized concepts of the self is a good starting point for understanding how the artists in this exhibition fashion themselves and their work in the context of hybrid cultures, academicism, and the weighty past of art history. During the Seicento, there was a sort of post-Michelangelo effect in which artists attempted to give expression to their individuality. The Roman Cathoic Church and the large sums of money that they promised for grand commissions enabled stylistic individuality. All of this, however, was in the service of the Church because Baroque ornamentation was a ploy to bring in the masses to the mass. Such tensions between the individual and the social continues today as artists vie for a position as the next art world superstar in an international scheme of biennials, glossy magazine spreads, and a booming art market, all the while criticizing the system. And like the Seicento artists who thrived from institutional support but saw themselves working to transform it, contemporary artists struggle to situate themselves within a capitalist culture of imposed obsolescence. Contemporary visual arts have seemingly less a social impact than at any other time in history. One might ask rhetorically, “Is nothing sacred?” And the answer is quite literally given in the question. The Baroque arts of today do not offer the possibility of transcendence through visuality. Instead, the contemporary Baroque values the struggle for secular and immanent human affect in the face of an ungodly capitalist machine.

The highly decorative superficiality of the post-Michelangelo age (which continues today) carries moral implications as well. The Seicento Baroque was seen to be a denigration of the beauty of the Renaissance, and in effect a reflection of the general degeneration of the society that produced such arts. Visually stunning and resplendent arts seemed to lack the deep and meaningful aims of the Renaissance, which strove for the Classical ideal. This judgment of taste appears accurate only because it is couched in a historical model where styles ebb and flow. However, the Baroque style was not an indication of a declining and immoral society. Such a judgment of taste bears little relationship to historical fact. Rather, the Baroque style reveals an interest in forms and themes that stray from the Renaissance and Catholic canon in the name of change. Hence the growing interest in the strange, the morbid, and the grotesque. If the Renaissance succeeded in achieving the perfection of an ideal, then the next step for artists was to turn was to the unknown. Artists during this period used the common narrative guises provided by common Classical or Biblical mythology but intensified the themes of violence, sexuality, and death. The giving of expression to these deeply rooted psychodynamic forces gave light to taboos that appealed to the Seicento sensibility very much, just as they do today. But the revelation of taboo need not lead one to consider the society that expressed these taboos to be corrupt. Rather, the topics of sex and death can reveal a desire for a libcrated society, especially liberation from oppressive religious and moral regimes.

Is the contemporary Baroque yet another attempt to instigate social change using traditional means, or is it a method for gaining value in a culture that pays little attention to the arts? The use of the Baroque is foremost an attempt to make art apply to a wide range of contemporary issues, from the cultural to the political, without having to give up traditional artistic means. Tradition is a tool ripe for conceptual appropriation, and a way to reassert art’s importance in a wider sociocultural arena without reverting to a hermetic and isolated idealism. Instead of being an art of negation, it is an art of inclusion. The return of the Baroque is on par with the return of figuration in the 1g70s (which reached a climax in the grotesque bodies of the 198os), the multicultural movement of the Sos and identity politicking of the gos. The return to the Baroque is a return to the joy of art making and viewing. If there was hope for the traditional arts after the Italian Renaissance, and if a selfsame hope exists after the decline of High Modernism, then it is achieved by a renewed sense of self.

Ultimately it must be asked, why is a cross historical connection necessary? Is it merely a token of Postmodernity that we can historically appropriate and consume past styles and other cultures as if in a shopping mall food court? Or is there some richer, deeper connection between a certain past style and our present condition? Surely an argument can be made that while some artists are looking back towards the Baroque age for inspiration, others may find sustenance in High Modernism, while others still try to achieve the ideals of Classicism. In any case, it is important to remember that the historical style that is being appropriated – whether Baroque or Gothic or whatever – is not being remade. There is no value in remaking the Baroque or any other past style. However, much contemporary art profits from a conceptual appropriation of the power of the past. An examination of what we have inherited can teach us about ourselves and our future. A side effect of such past looking may be that the historical style comes to be reinterpreted. However, this is only a secondary concern for the artwork in this exhibition. The Baroque age is not being promoted as a proto-Postmodern style. Rather, the Baroque is being used as a tool for understanding why a particular type of art is being made today, as it provides a link to our past that does not feel very distant.

Suggested reading:

Elizabeth Armstrong, Victor Zamudio Taylor, and Paulo Herkenhoff, UltraBaroque: Aspects of Post-Latin American Art (catalogue for an exhibition held at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art), 2000.

Mike Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History,1999.

Stephen Calloway, Baroque Baroque: The Culture of Excess, 1994.

Angela Ndalianis, Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment, 2005.

Brett Balogh

When viewed within the context of twentieth century minimal design and rapid technological progress, the Alchymical Analyser is an exercise in nostalgic anachronism. Although the practice of alchemy was losing merit in the scientific community of the eighteenth century, a few dedicated practitioners enlivened the magic of alchemy using then modern scientific approaches. Balogh imagines how the relics of a bygone technological era merge with magical and innovative thinking. The transformation of these antiquated materials is like alchemy itslef. Finely finished wood and brass components embellish the design of a computational machine using electromechanical telephone-switching technology. The logical architecture of the machine embodies that of a simple alchemical system in which four material qualities (heat, cold, humidity and dryness) can be combined, producing one of the four elements (Water, Air, Fire, and Earth). The user enters the desired qualities via a rotary telephone dial interface, and both the inputs and output are displayed on a back-lit, ground-glass screen. The work seeks to challenge the preeminence of modern computing technology and its bland ubiquity by invoking the logic and aesthetics of a bygone era, and thereby rendering the computational medium in a rich, sensuous composition of light, sound and sculpture.

Balogh’s artistic vision is to awaken the dormant or unrealized potentialities of the past. He does not accomplish this using contemporary technological standards, but steps backwards in time and builds machines ‘against the grain’ of history and in the guise of archaic design procedures. The alchemy instrument envisions how two seemingly opposite modes of knowledge (mysticism and science) can coalesce in a single form. The instrument thematizes the contemporary desire to approach and uncover the mysteries the past through the seemingly superior means of modern technology. Such an approach is of course futile and perhaps humorous, yet is insightful about the desire to turn the irrational into the rational.

Gillian Collyer

Gillian Collyer’s objects speak directly about the elaborate patterns and decorative functions of the Baroque, but are brought to a human or domesticate scale. The doilies, small and round lace crochet objects, are manipulated in several ways. In one series, Collyer cast them in bronze, which sometimes destroyed the intricate patterns of the doilies, and other times preserved their intricacies in an alarming way. Sometimes Collyer paints these objects with a gold finish, which sparkle and gleam in the light, and sometimes she leaves the surface as is from the casting process, which makes the cast doily look like an artifact from a long lost culture. For this exhibition, Collyer is producing a new series of doilies and is experimenting with new materials and dislay techniques.

Collyer often combines unexpected materials such as doilies with bronze or doilies with metal objects. The result is beautifully seductive, but the translation of the doily into metal or any other form that is not its original cuases it to lose its function, and provides a commentary on the uselessness of a valuable objects. Doilies have a genered association, and one would expect to see a real doily in one’s grandmother’s house on a hutch, perhaps witha porcelain figurine perched atop it. Collyer takes advantage of this association by “gilding the lily.” The lace crochet technique is traditionally frminine, and casting is a laborious and intense process that is typically signified as masculine. Additionally, whereas doilies are traditionally feminine, some of the metal objects inserted into them appear menacing or threatening, even grotesque. By combining these contrasting terms, Collyer asks if decoration should always be considered “pretty.” The subversion of “woman’s work” questions how femininity is made manifest in material objects.

Collyer’s objects are visually stunning, and yet they question the conventional scale of Baroque artwork by bringing them to a domestic or handcrafted scale. But the small-scale does retain a power to move the viewer. Collyer’s objects tend to overload the psychic capacities of the viewer by imbuing beautiful forms with a perceived threat to that beauty. The viewer is thus scared into the submission of the beautiful, and to accept whatever may lay hidden behind the guise of beauty.

Laura Emelianoff

Sound is often considered a metaphysical phenomenon. It exceeds its own physical origin and has a tunction in many types of ritual practices. With tones comparable to a pipe organ, and visual references to an iconostasis, or altar screen, this sound sculpture comes out of an abstract, pluralistic interpretation of the purpose of music and musical instruments in the religious experience: Catholicism embraces three dimensional arts, whereas Eastern Orthodoxy favors painting and forbids the use or ant instruments but the human voice in services.

This single, wall-mounted sculptural unit contains an acoustic stringed instrument whose sonic behavior is mediated by an electrical system of sensors and drivers, designed in collaboration with Brett Balogh. The instrument produces extreme bass frequencies at the low end of the human hearing range when sensors are activated by environmental movement or the proximity of viewers. These lower frequencies, sometimes called ‘the dark octave”, create stronger physical sensations than auditory perceptions. Rather than playing melodic pattern, the result is a complex timbre, a shifting blend of tones.

My work, although slightly less indulgent than what is called “baroque”, is hyper-sensual, making advantageous use of tonal variation, surface treatments, and the intrinsic values of raw materials. Here I am dealing with “human” proportions, in terms of both scale and auditory perception, yet address the possibility of a reciprocal relationship with the divine through sensory mediation.

Israels Etxatxu

Israels Etxatxu’s painting provides a nice counter point to Victor Maldonado’s art, another artist featured in this exhibit. Like Maldonado, Exatxu’s practice is concerned with the Mexican Baroque tradition, although the theme of humanity emblazoned by decadence is achieved using quite different means. This is quite apparent in Etxatxu’s skilled use of intricate detailing and somewhat garish blends of pastel coloring with gold. The painting here is a portrait, although the figure is drowned in opulence. A lace garment is wrapped around the figure like a mummy, as if the decadent material has consumed the person. In turn, the person’s identity becomes the garment and lace itself. Etxatxu’s use of paint is very fine and detailed, which draws the viewer in for closer inspection and rewards the viewer with the play of visual textures. This painting visualizes the extreme nature of the High Baroque, which comments on our love and desire for the ultra beautiful, the hyper-sensual, and the exquisitely irrational.

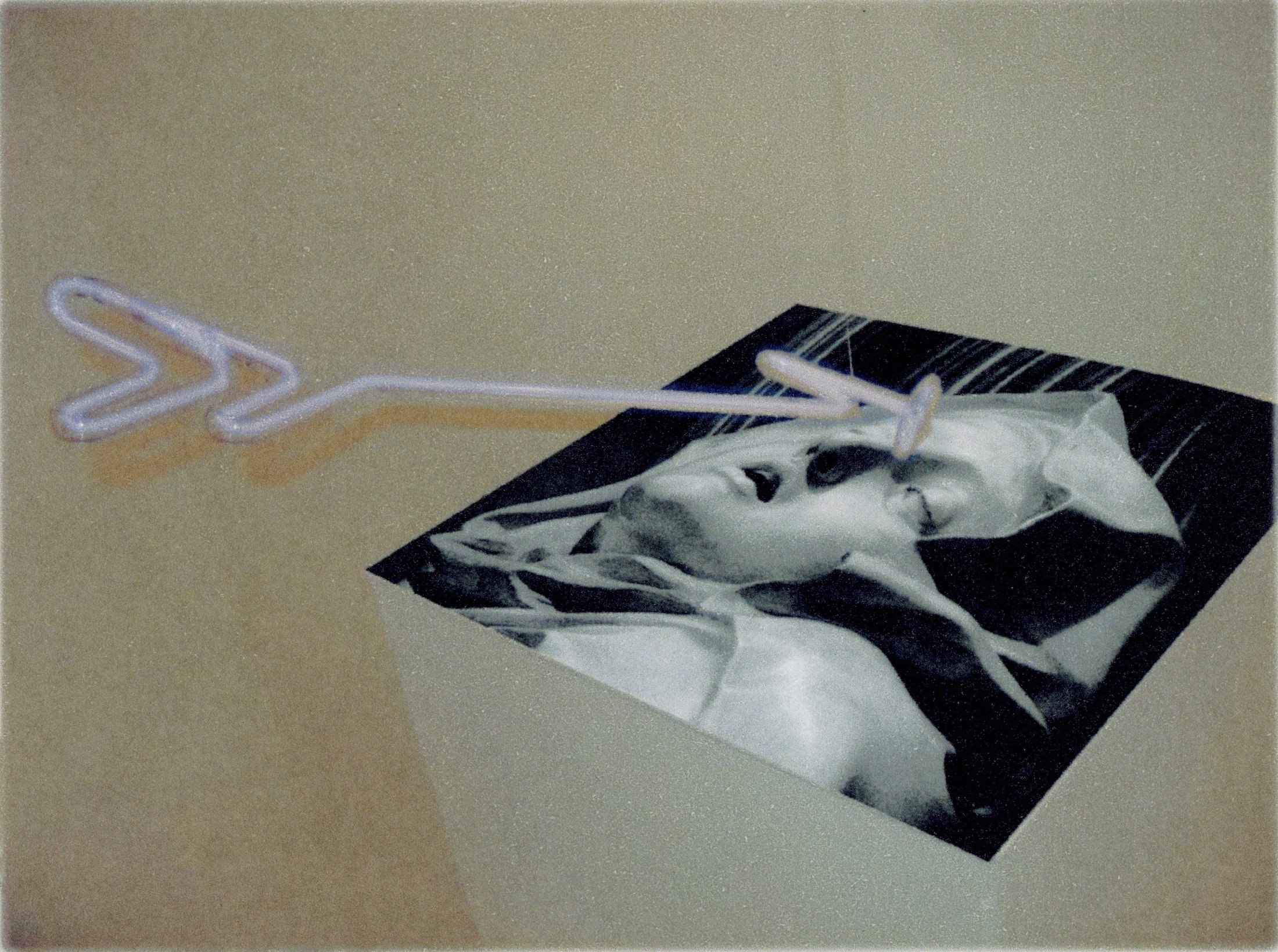

Thomas Gokey

Thomas Gokey’s update of Bernini’s St. Teresa in Ecstasy (c. 1647) re-envisions the mysticism religion through scientific terms. The sculpture by Bernini is a wellknown masterpiece of the Baroque era. The scene depicts Saint Teresa (a mystic who transcribed her rapturous visions of God) being pierced by an angel’s arrow. The arrow is the vehicle for the transmission of divine revelation and produces physical rapture. This scene has been widely speculated to be a representation of Teresa attaining an orgasm.

In The Full Dose of Joy is Pain, Gokey transfers the otherworldly mysticism of religion to the physicality and objectiveness of science. A neon arrow floats in mid air and is not connected to any electrical wiring. And yet, the arrow glows as if by magic, thereby producing the insight of divinity that was delivered to Teresa. A low-voltage Tesla coil hidden from view keeps the neon arrow constantly charged with electricity, which illuminates the arrow at random intervals, thereby delivering Teresa into rapture at the whim of a programmable technological device. Gokey’s sculpture allows the viewer to question if the prophet’s orgasmic revelation is really an impotent and artificial insemination of the divine.

Jessica Hargreaves

Jessica Hargreaves has often used herself as a model to represent a range of emotional states and situations. By employing allegory, Hargreaves shifts the focus from an individual awareness towards a more universal situation. The real subject of Hargreaves’ work then becomes a bittersweet yet often humorous depiction of experience in general. A common theme in Hargreaves’ paintings is the way in which each of us has moments in our lives in which we can perceive ourselves as simultaneously fulfilled and yet wanting.

It’s this feeling of fulfillment and of beauty alluded to but gone slightly sour that Hargreaves tries to convey through the use of color and figuration. It is as if the painted object were actually a piece of fruit that was riding the very edge of being overripe. Hargreaves encourages her viewers to indulge in the work’s lushness but with the awareness that the perfect moment of appreciation may have already passed.

Alessandro Keegan

Alessandro Keegan paintss large-scale works in oil that simultaneously attract and threaten the viewer – a truly Baroque strategy. A viewer may be seduced and drawn into the picture by its complex and seemingly familiar forms, but is then distanced from the picture once it is realized that the image may contain things that shouldn’t necessarily be looked at. We may be looking at a fantasical landscape, but are there cut up bodies and sexual organs in there as well? One may never know with Keegan’s work because it speaks in a combined figurative and abstract idiom that is unidentifiable. Keegan’s paintings reflect an unconscious dimension of associative, inter-locking, and complex visual imagery that illustrates the unformed but powerful psycho-sexual fantasies of the Freudian Id. In this way the viewer is drawn to the image because it is familiar, but is then repulsed by it because it is perhaps too familiar and hence dangerous. Keegan’s pictorial methodlogy contorts the conventional rhetoric of the Baroque but maintains its power to overwhelm and entice the viewer. By placing the viewer in a precarious position, Keegan allows for an introspective questioning of how an image produces affect.

Victor Maldonado

The European Baroque style was brough to Mexico during a period of Spanish conquest in the seventeenth centuy. Although this period of colonialism if often viewed as a violent exchange of goods and labor, the indigenous peoples, especially in southern Mexico, embraced the Spaniards’ introdution of the Baroque. The style has thus been assimilated into Mexico’s devoutly Catholic culture. Victor Maldonado’s work addresses the translation of the Baroque aesthetic, but also extends it by asking what would this stylistic tradition look like if it crossed yet another border, namely from Mexico to America?

Maldonado creates stamps of original and found objects and mechanically repeats them across the surface of the picture plane. This process combines the handcrafted tradition of Mexican folk arts with Mexico’s rich history of printmaking and revolutionary posters. Although th resulting images appear to be contrast to the extremely detailed work made in the Baroque style, the bold graphic forms and colors are actually quite powerful and seductive in a way that corresponds to the contemporary need to visually digest an image quickly.

Of interst when thinking of the Baroque is the “form” in motion and change as opposed to the idealization of the Classical. Mexico, a hybrid of indigenous Americans and alien Europeans, is itself an identity in motion.

Indigenous culture and religion in Mexico were transformed and then translated into

Catholic icons, almost undercover, as a way to sustain continuity in the face of colonial

assimilation. What are the things that we transfer, “undercover” of formal color and form? Can meaning be transmitted through the guise of beauty?

Set into the formal structures of graphic lines and rich colors, Maldonado’s paintings symbolically mix the cultures of cnsumer advertising, agricultural order and permutation, and industrial manufacturing with the artistic traditions of politically engaged revolutionary Mexican artists such as Jose Guadalupe Posada and the Social Realist Jose Clemente Orozco. The appropriated iconography in Flame of Color Field #1 speaks to Mexican-American culture and visualizes what a Mexican-American Baroque might look like. Maldonado creates images that delicately balance a humorous and pointed commentary on how our culture identifies with objects and images.

Armita Raafat

The Baroque style was created within a European aesthetic idiom for European consumption. And yet, the Baroque as a sensual and imaginative artistic endeavor is not confined to a Eurocentric vision. It is difficult to think about Armita Raafat’s Persian influenced sculptural installations without dealing with the Baroque. Raafat was raised in Iran, where the forms of Persian interior decoration have profoundly influenced her. The Iranían architectural fragments that Raafat’s sculpture responds to are often intricate, opulent, and made of very rich materials. Perhaps in a sense, they have always been “Baroque.” Raafat has spent the last few years in America and brought this aesthetic sensibility with her perhaps in order to make her new home more familiar by imbuing it with the forms that are meaningful to her.

However, any dislocation of culture does not g0 without translation. Raafat’s present artistic concern inscribes the traditional Persian interior architectural format into the undeniably Modernist (and Western) white cube gallery. Raafat’s sculpture responds to the blankness of the white wall and the rigid geometric architectural details that often go unnoticed within the spaces of utilitarian or objective architecture. The juxtaposition is not harmonious; it forces the viewer to ask why such forms must be positioned against each other. The result is contradictory and irrational but maintains a beauty of form. And this brings us back to the original aims of the European Baroque style. Raafat calculates her slyly subversive attack on the collision of differing cultural sensibilities through a traditional idiom.

Raafat’s sculptural installations are not only inscribed into the walls; they also drip onto the floors, announcing the process of their creation. The enunciation of this process is important tor Raafat because it declares that the sculpture- as well as its cultural implications -are conceived, executed, and propagated through artistic expression. Although the main component of the sculpture is tightly focused in one area of the wall, it is as it this over-saturated torm cannot contain itself. Pigment drips down the wall and piles of spices accumulate on the floor. The sculpture and its surrounding environs smell strongly of cinnamon and turmeric, thus adding yet another layer of cultural associations and abstrat sensual engagement.

Molly Schafer

Molly Schafer has a background in scientific illustration, and she uses this technique as a tool for revising both natural and mythic forms. For instance, she has noticed that classical depictions of the centaur are typically male, and she wonders what a female centaur might look liké. Often her centaurs have missing limbs, which she imagines to have been lost in an imaginary battle. This introduces an open narrative and negation of the Classical ideal into her work.

The highly skilled drawings are tightly focused in a small area on a large piece of otherwise blank white paper. This blankness serves as a conceptual framework for the figures. Without scenery or a setting, the figures become ideas only, and thus breaks the viewer’s desire for a full-fledged fantasy. The blankness serves to ask rhetorically, “what if?” The contrasting large scale of the blankness in relation to the small picture also serves to physically and optically draw the viewer into the tableau, but only to collapse traditional pictorial devices.

Schafer accentuates these drawings with sculptural objects that serve as an abstract analogy to the scene on the paper. In this new untitled drawing-sculpture hybrid, the gold painted coat hooks and rope references the doubled animal, and provides a tool for which the viewer may use to “capture” the animal. The gilded forms, which look like luxurious decorative objects, are upon closer inspection cheap mass produced tound objects that present themselves in a Baroque idiom. The objects, mirroring the drawings, are reveries of false desires: the kitsch object’ is for the consumer who wants an appearance of luxury, but is satistied with displaying it as surface quality only.

Schafer’s drawing/object installations pose yet anocher problem of the Baroque by using very simple or minimal display technqiues. The large expanse of white paper denies visual play. The visual play is instead offered in the form of the seemingly luxerious objects accompanying the drawing, but is not fulfilled because the objects are presented as fragments. In other words, they do not contribute to a density of visual information that is customary for the Baroque. Schafer removes the context from the Baroque and displays it as if under a microscope and asks the viewer to question how objects can assert visual power.