A new scholarship and recent exhibition pay tribute to a much-loved SAIC professor and artist who influenced everyone who met her.

Time. Time was a commodity Barbara DeGenevieve used efficiently. She was booked solid, even penciling in time for sleep in her planner. It was a running joke among her SAIC colleagues that during an hour spent with DeGenevieve, her phone would ring 30 times—she was valued for her opinions and advice, and she made herself accessible in many ways.

DeGenevieve was an SAIC professor, artist, and Chair of the Photography department. Her time with the school, almost 20 years, was marked by the remarkable relationship she had with her students as well as an honest, unfiltered teaching style that her pupils respected. She taught a class called Body Language, which was nicknamed “Porn 101.” She understood her students’ individual needs, advocated on their behalf, and considered them colleagues. She held office hours late into the evening, on days off, and even opened her home to students for “marathon critiques.”

In the classroom, each of her students was given a full hour of thoughtful discussion. With 10 to 15 students in each class, these discussions were an all-day ritual, often continuing through the night. Her students reciprocated her commitment with respect and loyalty; they were always on board for the duration of this formal discourse. “Her service to the school was immense, invaluable, and never-ending; she never stopped,” SAIC colleague, collaborator, and Adjunct Assistant Professor Oli Rodriguez says of her unwavering devotion. Time was also something DeGenevieve was never allotted enough of. She died of cervical cancer August 9, 2014, at the age of 67.

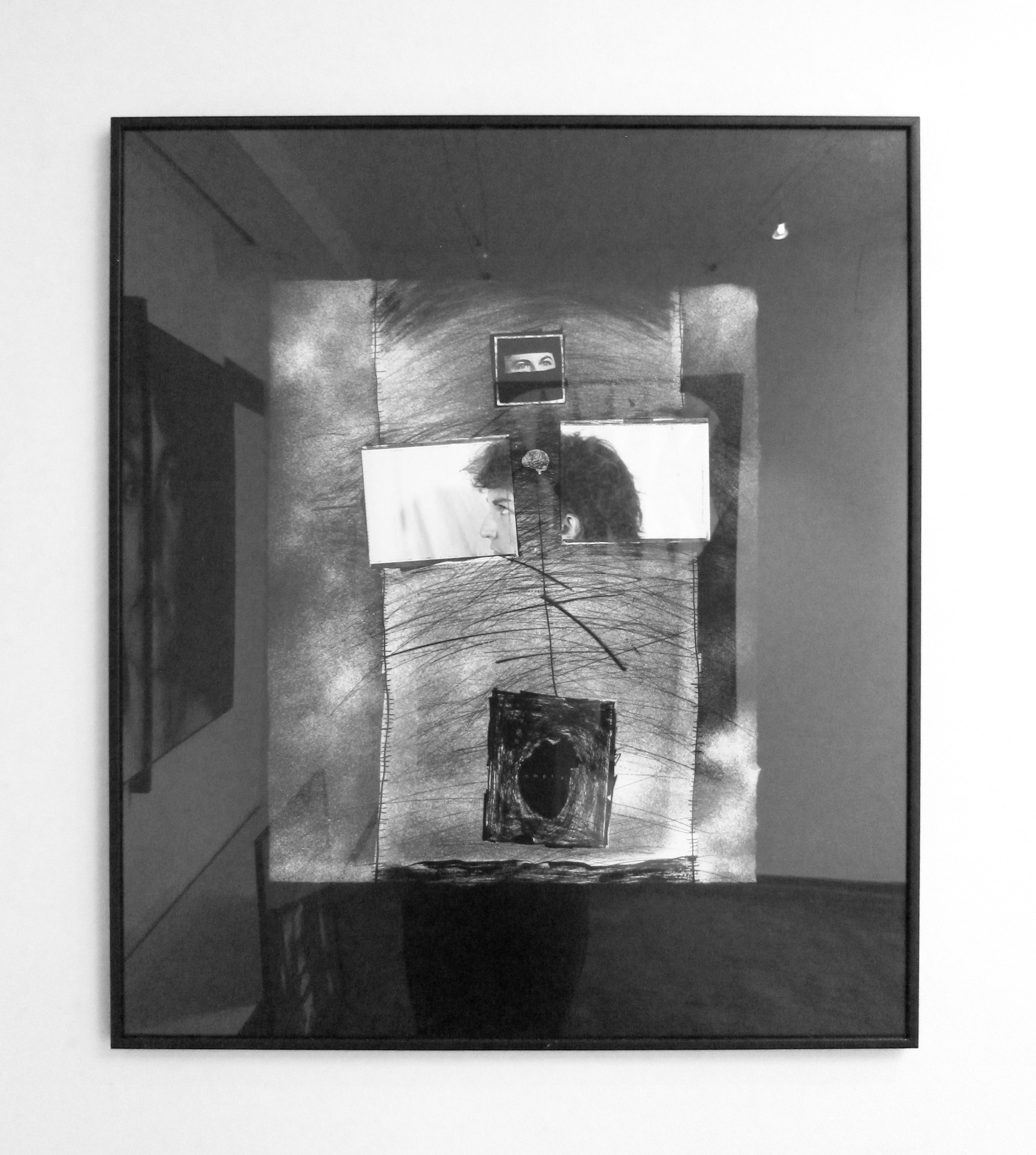

Barbara DeGenevieve, Untitled, 1985–92, from the Cliche Verres series. Photo: Michael Madrigali

The SAIC community recalls her brazen ideologies, unflinching courage, and humor and grace in the face of critics. In her artistic practice, DeGenevieve confronted the abject. Her work was provocative for the sake of discourse, never shying away from issues surrounding race, class, gender, identity, censorship, and artistic liberty. She challenged convention, stereotypes, and notions of propriety—and she did so with a fierce spirit. That is not to say she lacked an acute sensitivity. According to Adjunct Professor and Associate Provost of Educational Technology Alan Labb, her work “ was never a simple documentary—she became involved with the subject and she herself became an object. She blurred the lines she crossed…she wanted to move what was on the fringe closer to the center.”

In both her portraiture and videos, DeGenevieve gave her subjects dignity and agency in an intimate way, finding ways to serve them in return for their participation. Her best-known example is the Panhandler’s Project, an intimate series of portraits depicting Chicago’s homeless men. In exchange for a few hours of participation, DeGenevieve provided a hotel room, food, clean clothes, and monetary compensation; however, the most significant aspect of the work, evident in the video component, was the comfortable dialogue and sincere interaction. Assuming this vulnerable role meant that the camera was often turned on her. “She was always a part of the work, even when she wasn’t pictured,” notes Rodriguez.

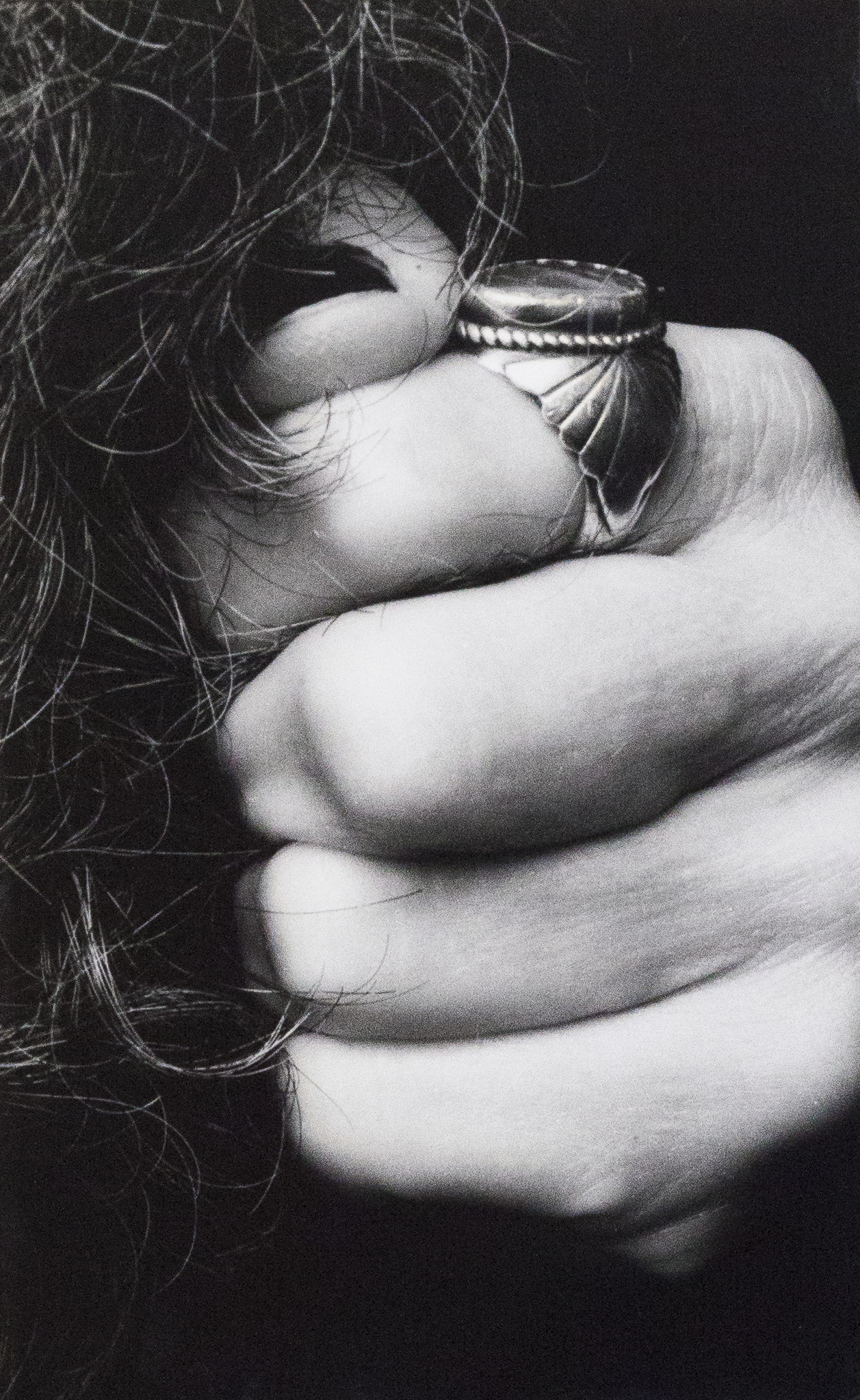

Barbara DeGenevieve, Fist, date unknown. Photo: Michael Madrigali

Putting her students first, DeGenevieve never had enough time to dedicate to her own practice. One of her last requests was a final exhibition. It took an army of graduate students, friends, and faculty, headed up by Labb, to unearth, preserve, and document decades of DeGenevieve’s work. From this archive SAIC Board of Governors member Daniel Berger and artist Doug Ischar developed the exhibition, Medusa’s Cave—named after DeGenevieve’s online pseudonym. Held in Berger’s Rogers Park gallery, Iceberg Projects, the show was the artist’s first solo exhibition and retrospective.

The exhibition, which ran from September 12 to October 10, 2015, emphasized works from earlier in her career, depicting her breadth and development as an artist. The show included vulnerable and deeply personal work that demonstrated who she was as a person, not just an artist. Discussing the prominent self-portraits in the show, Berger says, “They are not only utterly imposing as they are gorgeous, but they portray her sense of humanity and fearlessness.” The work gives agency back to a sensational and often sensationalized woman.

Barbara DeGenevieve, installation view of Medusa's Cave. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

On the closing night of Medusa’s Cave, Iceberg Projects screened DeGenevieve’s recent and well-known video works. Students, faculty, colleagues, and disciples gathered for the commemorative night, many traveling across the country just to attend and reflect.

For Berger, the exhibition was not enough. He created a scholarship in memory of the late professor, out of a “need to honor her and allow the continuation of discourse of her legacy and memory.” The Daniel Berger Barbara DeGenevieve Graduate Merit Scholarship Fund supports an MFA graduate student in the Department of Photography as well as honors DeGenevieve’s artistic legacy. Renluka Maharaj (MFA 2017) is the scholarship’s first recipient.

Time went quickly for DeGenevieve after her diagnosis. Few people in the SAIC community knew how sick she really was because she continued to put others first and unabashedly moved onward. Labb recalls accompanying her on doctor’s visit. The oncologists asked DeGenevieve what her plans were for the next five years—what was going to inspire her to get better? Her answer: “I want to teach.”

DeGenevieve’s life was cut short, but she left behind a great league of devoted people who care dearly for her and who will ensure that her courage and spirit will live on.

Barbara DeGenevieve, installation view of Medusa's Cave. Photo: Jaclyn Silverman

,%202014,%20performance%20and%20sculpture%20at%20the%20Drawing%20Center,%20New%20York.%20Photo_Lynne%20Heller.jpg)