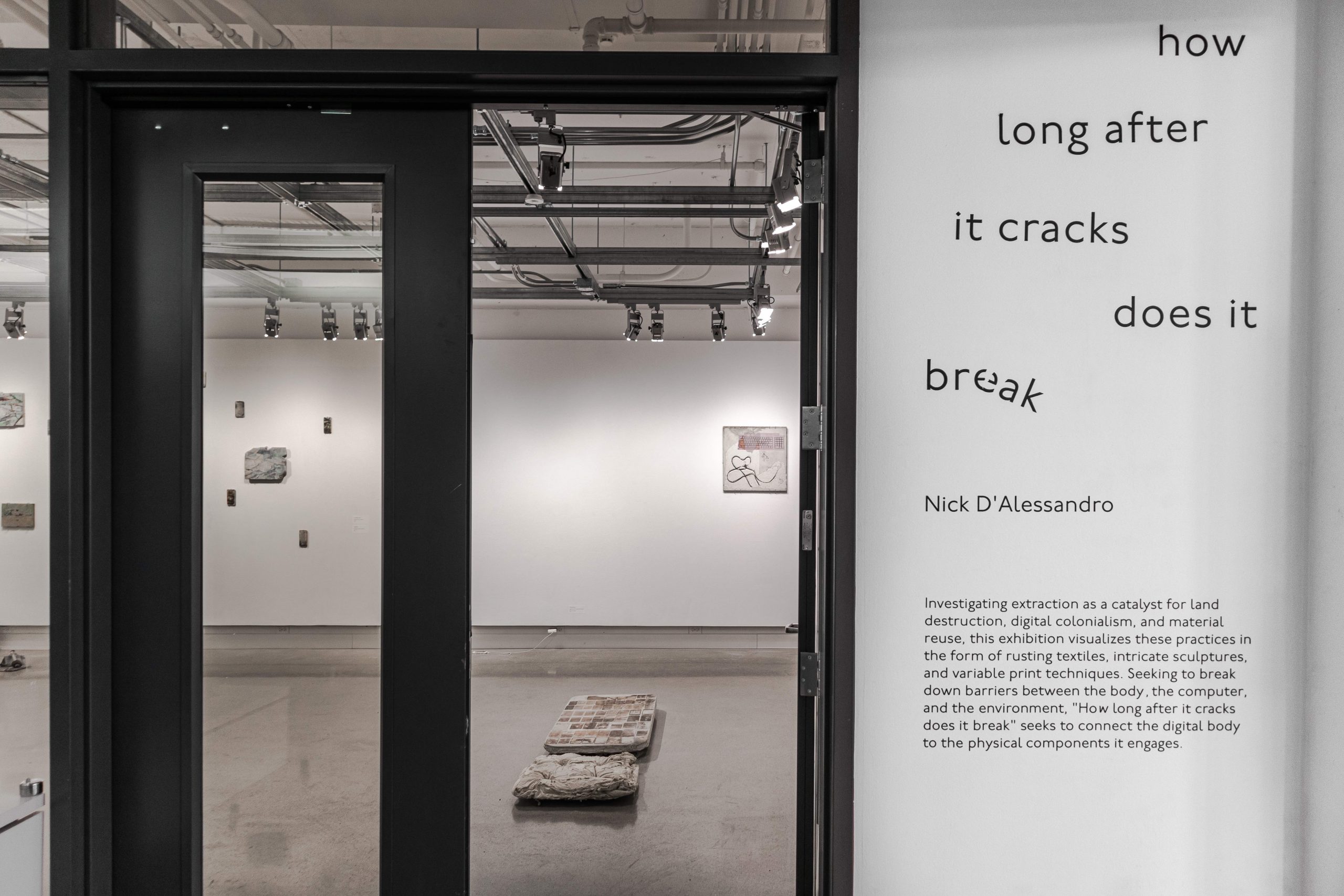

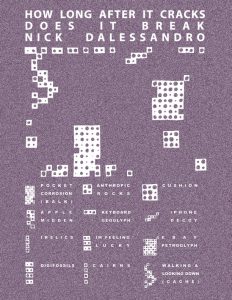

How long after it cracks does it break

Nick D’Alessandro

February 9 – March 9, 2023

SITE 280 Gallery

Photography by Veronica Rósas

Contributing Artists

Nick D’Alessandro

Exhibition Statement as Preserved in the SUGS/SITE Archives:

How does it feel when your fingertips touch another’s through the glass of the screen? How does your phone’s rectangular aluminum frame fade the pocket of your jeans? What would the rust swamp of an electronic waste site look like if left untouched? How long before the screen cracks does it break?

How long before it cracks does it break (2023) is a collection of works that investigates the extraction processes necessary for the creation and degradation of the iPhone. Precious metal mining and algorithmic data manufacture result in land destruction and lead to digital colonialism.

The extraction of technologically critical elements (TECs) consumes immense amounts of energy, generating a massive carbon footprint when mined and discarded as waste. Data has become the most valuable resource, with experimental algorithmic data collection being tested in regions where individuals are unprotected online. Mining, in the context of both digital and physical spaces, requires exploitation in order to be profitable. With technological infrastructure requiring massive amounts of electricity and data mining using private information in order to increase consumption, the digital future is being built on oppression and assumes human supremacy over the earth.

Waste as a landscape marks the point at which our control over the earth ends and a new contract with it begins. The traces of this waste become fossilized into our planet’s geology, and without animation by their digital content, these objects become nothing but relics of our impact. This

flattening of objects occurs in the transformation from object to waste, but also is promoted in digital spaces. In order for one’s digital self to be easily consumable, the multidimensional self is reduced.

Seeking to break down barriers between the body, the computer, and the environment, How long before it cracks does it break invites the viewer to reconsider how we value objects and invites a deeper consideration of the history and context of natural and manmade objects. Considering the body as both the site and the receiver of so many harmful extraction processes, the work investigates our connection to the earth through the aluminum rectangle in our pockets and seeks to connect the digital body to the physical components it engages with. Hyperconsumption and the waste we produce as a result of global capitalism leaves an impression on our planet and ourselves. Processes of replication, fossilization, and abstraction

are presented in the work to suggest a nuanced cyclical extraction practice within a sustainability framework.

Different components of these extractive processes are represented in various parts of the exhibit. The wall of an electronic waste mining site, which has degraded into rusted iron, patinated copper, and opaque steel, sits beside the minerals which have been extracted

Copper, aluminum, and iron are suspended in wax molds of broken electronics. iPhones, iPods, and headphones sit stacked waiting to be smelted down into the forms that they had existed in prior.

The private algorithms of individuals are showcased in public, destroying the false sense of privacy that we are promised in using and personalizing our apps. Algorithm-derived TikTok screenshots are screen printed against aluminosilicate glass, and superglued to the device which has petrified into solid concrete. An iPhone decoy rests plugged in on the floor, acting as the idol for the exhibition.

Desktops of both old and new computer screens are compacted together to suggest the rapid acceleration of consumption in the digital age. Shattered concrete slabs are printed with Google Earth-rendered landscapes to highlight the digital artifacts through which we experience the natural world. Fragments of cracked concrete pieces sit stacked on the floor as cairns, guiding the viewer through the space.

Steel forms are stretched with nylon, printed with AI-generated images of future geology and littered with e-waste as an ode to the natural environment, and our digital recreation of it. In the center of the room sits an artifact of our time, a fossilized impression of our present. The imprint of 72 broken iPhones printed with metals which seep into a concrete slab, mirroring the way technology will embed itself in our planet’s geology. Swathed in a hand-mended canvas cloth and piled atop rocks, sand, and earth-borne elements, the central fossil reminds us that our actions are not singular.

Programs

February 9, 4:30-6:00 PM

280 Gallery

Performance

March 2, 4:30-5:30 PM

Program statement from the SUGs/SITE archive:

“I invite viewers into the gallery space where I am seated on the ground. Above my head sits my phone number. The viewers are invited to text me, where I will be holding a Q&A between myself and the viewers. Using the screen as a method of separation between us, our physical presence will be close to each other, but the distance between us will be felt as a result of the screen. Silence is encouraged but not required. Seeking to extract a conversation into written text, the conversation will exist far beyond the interaction. The conversations I have with others will embed themselves into the iPhone as an object, immortalizing the discussion. The conversations will also be recorded in real time, and displayed on a projected image or a television screen, which will be active both during the performance and after it is complete.”