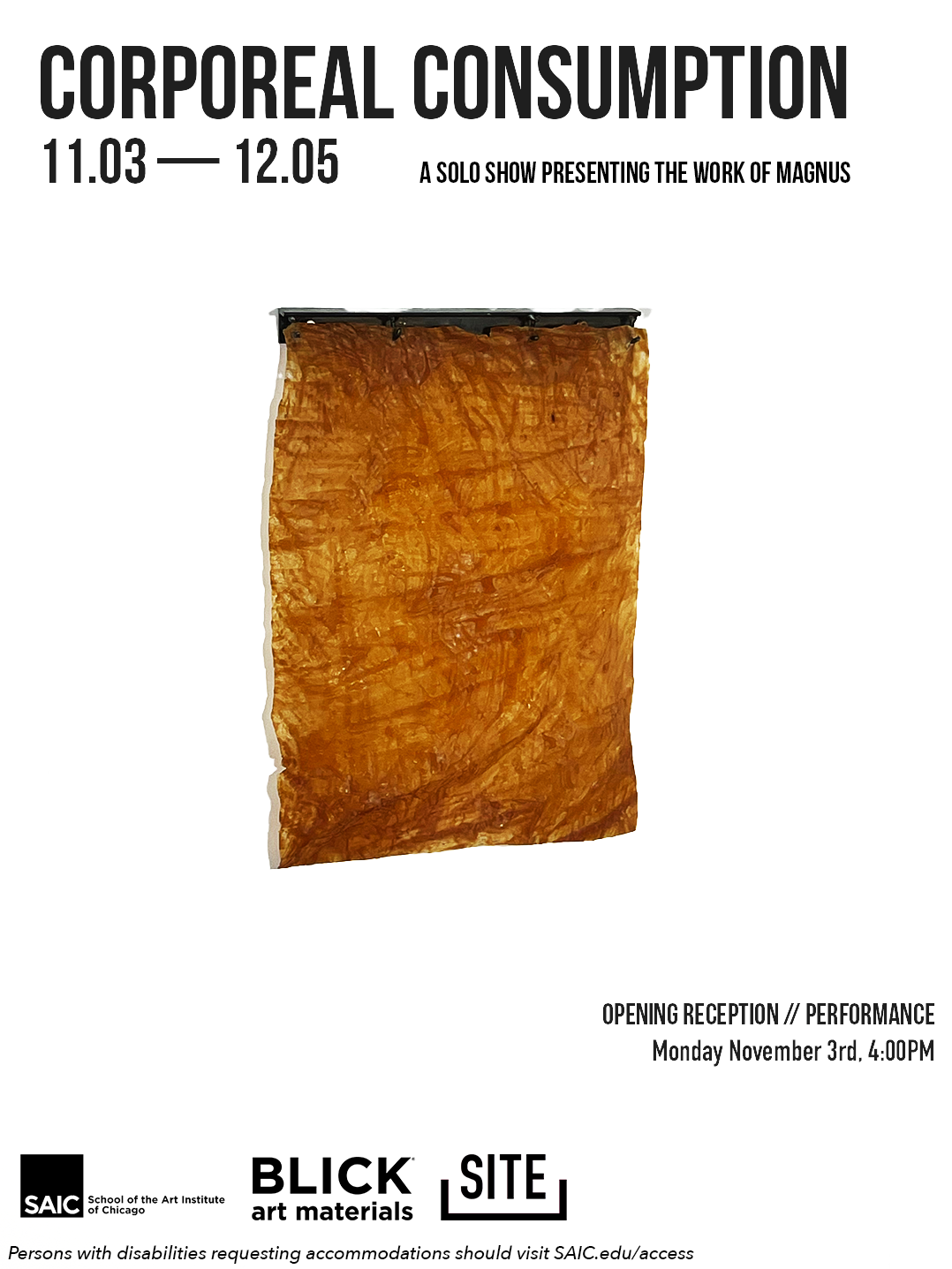

Corporeal Consumption

MAGNUS

November 3 – December 5, 2025

SITE 280 Gallery

Contributing Artists

MAGNUS

Exhibition Statement as Preserved in the SUGS/SITE Archives:

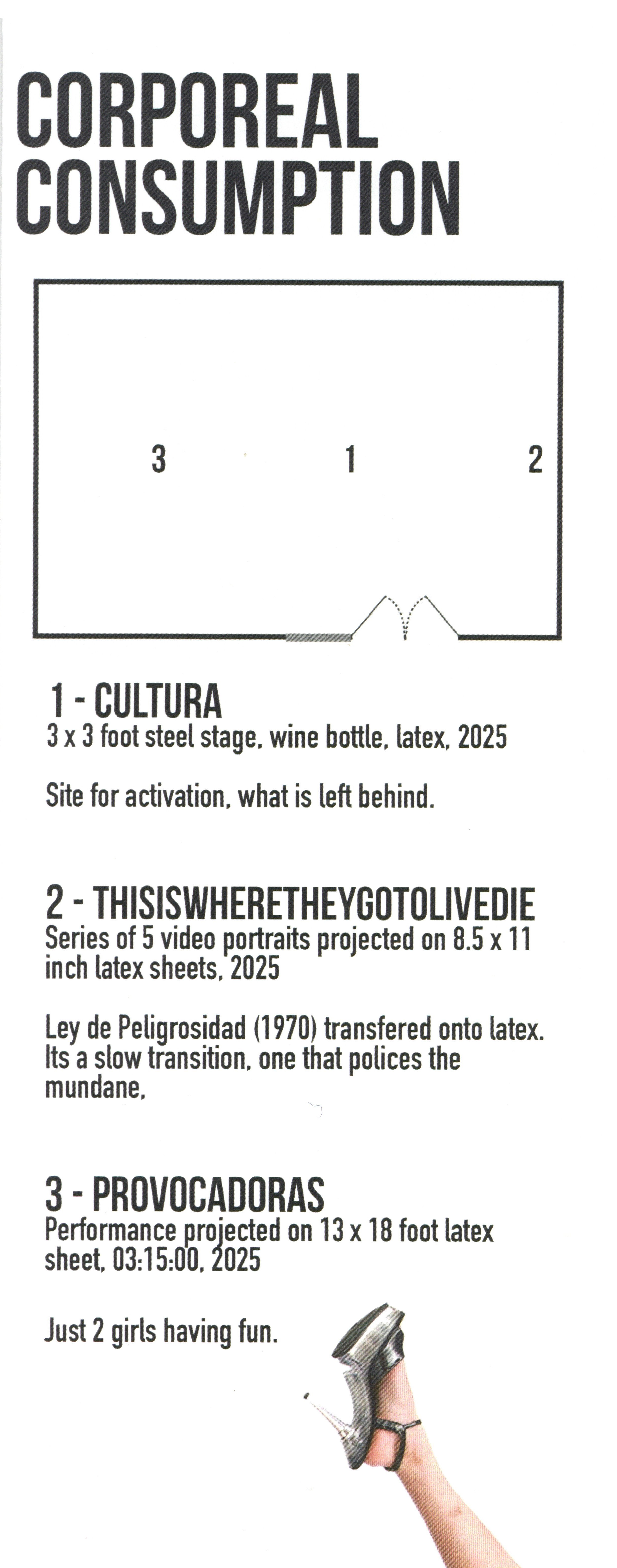

Corporeal Consumption is an exhibition exploring the materiality and visibility of the queer

body within institutional and heteronormative spaces. Through stretched latex surfaces

and projected imagery, the exhibition interrogates how queer bodies are consumed,

regulated, and rendered both hypervisible and absent.

Inspired by the Uncanny and rooted in a self-defined practice of queer material language,

this work uses latex as a “second skin” to question where the body ends and the artwork

begins. Nationalist iconography is appropriated and queered, offering a subversive

response to the sanitized aesthetics of institutional display. The minimalist environment

mimics the “white box” while exposing its hidden violences.

Programs

Opening Reception

Monday, November 3rd

4:00-6:00 PM

SITE 280 Galleries

Interview With Magnus

What’s your earliest art memory?

I feel like creativity has always been with me, but art-making came later. I remember making little hotels and houses out of my mom’s shoe boxes. And I still have this one memory where I would add a string to a little box and make a moving elevator. But looking back, I never thought of it as art-making. I feel like I’ve always been this weird, creative gay kid, and now I’m becoming more comfortable with the idea that I am an artist, even though I feel like everyone is to an extent, you know.

Your work makes vast and varied references to latex as a “second skin,” When did this material first capture your imagination? How did it come to hold such meaning to you?

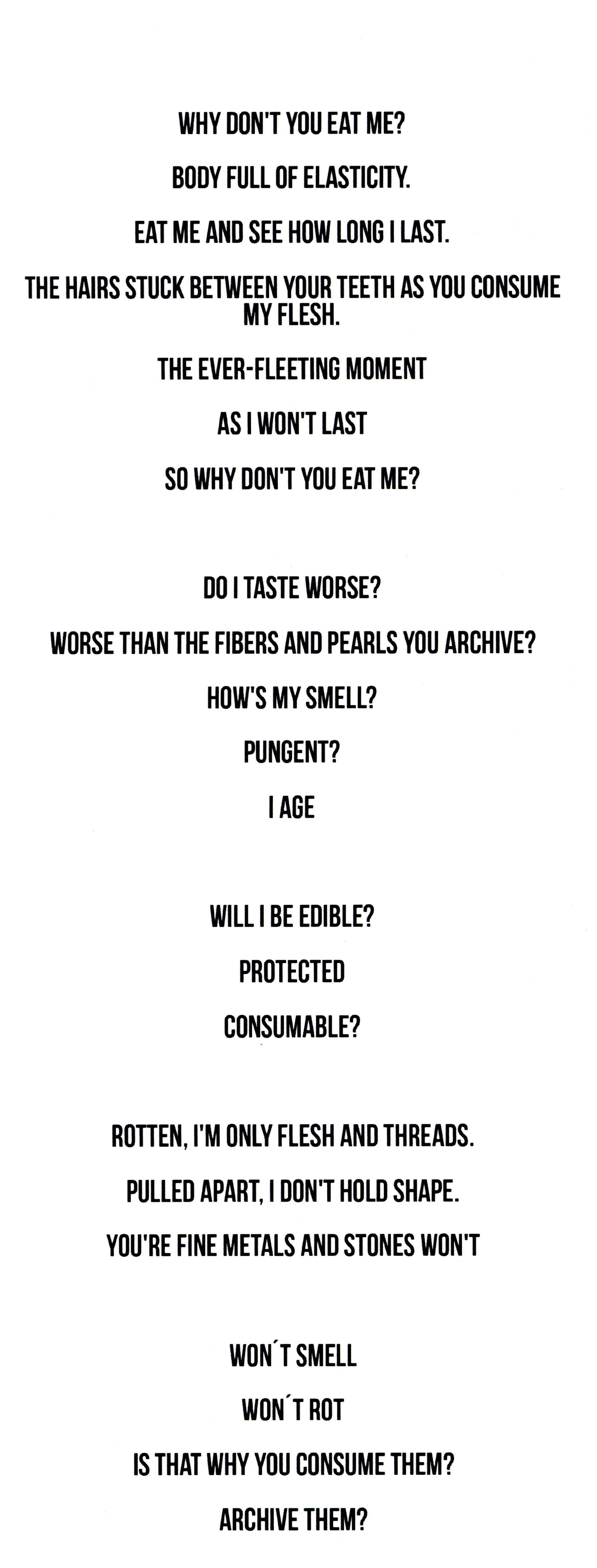

I was a repressed little f*****t, and I didn’t know how to get into my queer side, so I got into SFX makeup. And that’s where I got into things like liquid latex and prosthetics and stuff like that. And that gave me a little avenue to, like, sneak into my mom’s bathroom where I’d do more drag makeup and more queer things, whatever, like wrap towels around my body and act like it’s a dress—the usual kind of story. So I think that was my first introduction to latex, and then coming here, and exploring what art making means, I realized that somehow I could use my first idea or my first exploration of queerness — which was through SFX makeup — and combine it with a more minimal kind of language, or play with the materiality of latex itself. And playing with its materiality got me thinking about the body, and abstracting the body, and the fetish body, and the provocative body, and all of these weird elements of what the body is. I try to be super general on the body, because I think it’s harmful to refer to the body as “the body,” but I think there’s also a use to it when you keep it so general in the sense of like, what body are we talking about? For example, I love to have an open ended “they.” What is this “they” and who is this “us?” I’ve never really defined where the separations lie, because that’s how they get you to agree to something without fully knowing what you’re agreeing to, if that makes sense.

How is it harmful to refer to the body as “the body?”

Because we purely objectify it, right? We say that there’s just the body as a physical object and nothing more. And there’s a sense of truth to that, of course. I’m not super spiritual, but I do understand the dangers of referring to a body as a body and nothing else.

The large video piece in this exhibition deals with how some of our actions can be seen as provocative despite us not intending them to be, can you share a time when your work provoked an audience in a way that you did not intend or expect?

This is so stupid… I remember I was on my gap year in Berlin and did a little exhibition with some friends of mine. I showed this work where I’m sitting on an egg. It was this looping video of me trying to lay an egg, but I can’t because I’m a man, so I just sit on it and crush it. And someone came up to me saying, “I don’t know if I like the underwear you were wearing.” And I was like, what? How did we get to the point where I’m now being critiqued for what I was wearing instead of the actual piece? And they went on like “oh, it would be cuter with a little thong.” Mind you, I don’t even know this person.

As a performance artist, do you ever get stage fright?

Yes.

How do you deal with it?

Weirdly, I don’t know. I think you just have to get on there and do it. It feels like blacking out. Like you know what you’re doing, you know you’re performing, but then all of a sudden you’re done. And anywhere from a five-minute to a two-hour performance, it feels like something takes over your body. It’s so strange. The fear of failure or the fear of the audience only happens before and after the performance; you never feel it when you’re actually on stage. For my performance activation at 280, there was a projection, and for the 20 minutes that I’m waiting for the audience to come in, they could see my shadow; they could see that I’m there right behind the latex. And that made me think, “ok, when am I actually performing?” Because I didn’t have stage fright in that moment, but then one second before I’m about to turn around the corner and see the audience, that’s when it swallows me up. But then right after that, it’s over. You got it. You don’t even have time to get scared because it’s such an adrenaline rush. I love it.

What was the last book you’ve read? How’d you like it?

I’ve been reading two books. Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin and The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt. So a love story and an authoritative… what is it? It’s literally just talking about fascism and communism. There’s a lot more to it obviously, I don’t have to get into it, but political philosophy’s always in the back of my mind. And my artistic background is Pierre Molinier, Ocaña, Claude Cahun, the Surrealists, eroticism, and these kinds of provocateurs. I’m really interested in how those elements work together in the same way that an authoritarian government polices and sexualizes the body. So then the body becomes kind of like a revolutionary site. I don’t think the work that I’m making is inherently provocative, but I believe that they stand as a space of provocation because of the context or state, and I think that is a fascinating tension. How does that happen? How does the body change slowly? Transition has been so important to me as well. These states of ambiguity, where you don’t know when fascism is here, you don’t know when it’s not. Is that a man? Is that a woman? Is that skin or is it not skin? Are we doing real labor, or are we performing labor? It’s that ugly space right in between, that constant doubt.

Do you have any daily rituals?

I smoke. I smoke a good joint right before bed. What else? I’m a writer, so I always try to write. Weirdly, I feel like I’ve left doodling behind with this f*****g minimalist bullsh*t practice that I’ve developed, so I don’t really draw as much anymore. But I do write a lot. I have a small notebook where I write my phrases. And they could be anything, like “I saw a manhole that was uncovered today.” That’s the most private and consistent thing I do.

Your exhibition interrogates how queer bodies are “consumed, regulated, and rendered both hyperinvisible and absent” within “institutional and heteronormative spaces.” What do you believe is the biggest challenge that queer artists face today?

I think it’s that we’re in a transitional time again. We live in this weird time where we have the language of — this is going to sound so cliché — the language of liberated bodies, or the language of progressiveness, but we don’t have the institutional actions to back it. We’re not protected, and whatever protections we do have now will be slowly taken away. I think what makes queer artists provocative will only become worse and more mundane in the sense that — I mean, we’re seeing it now in Texas just this week, they passed yet another anti-drag bill. So now you can get fined or sent to jail for publicly showing drag. And we all know how that slowly shifts into, for example, prosecuting the trans community everywhere in this country. So it’s going to get worse. Our existence is purely a provocation to them.

Something I’m still figuring out is which language I should use. Should I always take into account the language of others? The language of people I don’t fully understand or agree with? I don’t need to, but part of me still, for the sake of communication, thinks a lot about that. So it’s about choosing who we’re making art for and which spaces we’re going into. Because there’s galleries out there that want our art, who want queer art, but don’t really support us. As queer artists, we just have to be even more picky. Picky where we show, who we work with, etc.

If the Art Institute was on fire and you could only save one artwork, which one would it be and why?

None of them they should all burn! [laughs] Ok, listen, I’ll give you my pretty answer and my honest answer. There’s an object by Claude Cahun, Object 1930-something, that I love. There’s Eva Hesse’s Hang Up that I also f*****g love. And Portrait of Ross in L.A. by Felix Gonzalez Torres, but I don’t think it’s in the contemporary wing anymore. So those are my favorites, but, and this goes back to my practice, I love latex because it’s not archival. You could try to preserve it, but it’s probably not going to last more than 50 years. And I really think that should be how we consume culture itself, it’s ephemeral and fleeting. I think we’re so focused on cultural consumption through inanimate, stagnant objects rather than through people. There’s this eerie sense to museums like the AIC where, I imagine, if all of that wealth and power were there to protect the hands that made all those objects, that made all those cultures and societies, instead of just grabbing these objects and cultures and placing them in cages. There’s this weird idea of consuming culture in a vacuum, that it’s not in communication with itself. Like this is the European wing, and this is this wing, and this is that wing. It’s as if they all exist in a vacuum when that’s never been how cultures arise. Culture is constant, it’s ongoing, it’s always shifting. I think museums have this paralysis of culture; it’s stagnant, it’s all in objects. And I do love these objects, I believe there are reasons to care for them, but when we’re not caring for the people, what is the use? What is the use of having some Greek f*****g statues? But that’s besides the point; if they burn, they can burn. That museum would look really cute after all, techno-grungy and covered in soot. Then they could raise my tuition if they want [laughs].

Interview conducted and edited by Eugenio Salazar Castro