…we all know that. Between the increased use of robots in factories and the appearance of artificial intelligence everywhere—from trucks on the highway to check-in kiosks at hotels, airports, and doctors’ offices—much of contemporary technology is focused on trying to eliminate the variable of human labor. As capital seeks ever-lower costs for production and ever-greater margins for return on investment, we need to ask what happens to our social contract and our social space when workers continue to be displaced from their jobs and sources of income.

Across continents, garment workers are subjected to working conditions most consumers couldn’t possibly imagine in order for each pair of jeans they produce to meet profit margins that are pennies on the dollar. As big box stores continue to meet the demands of low wage consumers and as executive pay continues to rise in relation to employee compensation, income inequality threatens to disrupt our democracy. Where is this all heading?

We read that the monthly unemployment numbers keep going down, but on the very same front page, we’re told of the crisis in low wage work that can’t sustain a life outside of poverty or precarity. The federal minimum wage remains at an unsustainable $7.25 an hour. Why are maintenance workers, care workers, and women so inadequately compensated?

Whether it’s the free labor of an intern in a cultural organization trying to get that recommendation or line on their CV, a migrant agricultural worker moving from state to state, or a care worker sending remittances home from half a world away, the rules of who gets paid and how much remain a complex enigma.

It’s called a social contract…but many of the jobs people now work no longer provide the security they need, the self-respect they’re searching for, or the ability to think about the future, all necessary conditions for a social contract. And for a generation of students with enormous loan debt—currently at $1.6 trillion and rising—there’s little time to figure it out.

Of course the subject is much too complex to consider fully, but as a college of art and design our task is to provide contemporary representation and sensual interpretations that engage these urgent questions, address these recent and unrecognized histories, and participate in producing a sustainable democratic future.

With RE:WORKING LABOR we want to produce not one conversation, but overlapping conversations—perspectives that touch one another: from the very local idea of how cultural labor is organized to the representations of contemporary labor that artists are capable of producing, from global perspectives of waged labor to the critical issue of anthropogenic climate change in a world driven by accumulation, expansion, and acceleration. These perspectives shift in scale and scope, yet speak to each other in fundamental ways.

Our task is to get the conversation going.

![]()

As inaugural fellows in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s (SAIC) Institute for Curatorial Research and Practice, we were confronted with an extraordinary opportunity to rethink the nature of what a curatorial research fellowship could be and also to consider in a time of political instability what might be our most essential responsibilities.

Our project began at a moment of great consequence and urgency. The 2016 election foreclosed many exhausted assumptions that were widely taken for granted: the immutability of globalism, the permanence of neoliberal economics, and the supposedly equal opportunities inherent in a meritocracy. The vacuum of their disappearance was quickly filled by destructive resentments and the triumphal reappearance of racialized politics.

What happened? Why didn’t we see this coming? Misled and misinformed by trusted news sources and polls, we had to examine our culpability for accepting their authority and expertise and reflect on our own complicities and privileges. Had we also forgotten those in economic distress while paying too much attention to the issues of our own circumscribed communities?

These new conditions confirmed the necessity to take time for independent research, to discern facts from opinions, and to explore the backstories and circumstances underlying what wasn’t anticipated or comprehendible. This research led inevitably back to the economic crisis of 2008, to the pressing issues of work and underemployment, and to the abandonment of communities in the industrial Midwest and Appalachia. It also led to historical considerations of structural income inequality, a tax system that privileges capital over labor, and conditions, such as the offshoring of manufacturing and the rapid technical developments in robotics and artificial intelligence, that continue to destabilize the workplace.

As we developed a plan for the two years of the research fellowship, we asked these key questions:

- How can we bring to consciousness the many underlying forces that destabilize daily life, our economic choices, and our futures?

- How do we work across boundaries to produce something different, more effective?

- How do we challenge hierarchies, rules, structures of authority and authorization?

- How do we reinvigorate the curatorial process?

- How do we balance risk against the known, the predictable, and the expected?

- What can a curatorial fellowship in an art school do?

- What can an exhibition at a school of art and design produce that a museum exhibition can’t?

- Our response to these questions is the project, RE:WORKING LABOR.

We began by casting our net widely and connecting with an extensive network of artists, academics, social activists, and students. Over the course of two years, we developed a three-part plan that included an international symposium, an exhibition, and a subsequent publication.

The international symposium, RE:WORKING LABOR, held at SAIC in October 2018, was a close, institutional collaboration with re:work, the IGK International Research Centre “Work and Human Lifecycle in Global History” at Humboldt University in Berlin, where historians, anthropologists, sociologists, and occasionally artists share their work and reflect upon the work of others. Their program contextualizes work and life course, technology, capitalism, colonialism, and the movement of peoples through migration, both geospatially and inter-culturally. With this global perspective, we set out collaboratively to produce the symposium.

The structure for the symposium brought diverse disciplines and voices together, with the morning session centered on the ways artists conceived of contemporary labor and how their work produced those representations.

The afternoon session was centered mainly on a consideration of the many social contracts that work produces, how work forms our social space. The presentations touched on how labor regimes reflect the complexity of gender, race, class relations, and their fundamental connection to the labor of social reproduction and the forms of labor that remain uncompensated, unrecognized, and unrepresented.

For the second day of the symposium, forty guests from diverse backgrounds and disciplines broke into working groups. They were asked to imagine an expanded notion of exhibition and to consider possibilities for collaboration. These conversations and interactions were the foundation for the second part of our project, the current exhibition RE:WORKING LABOR at SAIC’s Sullivan Galleries.

Out of the symposium, we organized four large-scale anchor projects: a new work and performative action by Mierle Laderman Ukeles presented with earlier documentation of her historic work, Touch Sanitation; an installation of Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki’s global project, Labour In a Single Shot, coupled with a 17 day free workshop for Chicago participants conducted by Ehmann and Eva Stotz that will add to the work’s archive; a screening series comprised of five contemporary media programs curated by Aily Nash and Andrew Norman Wilson entitled Image Employment; and a newly commissioned work by Ghanaian artist, Ibrahim Mahama.

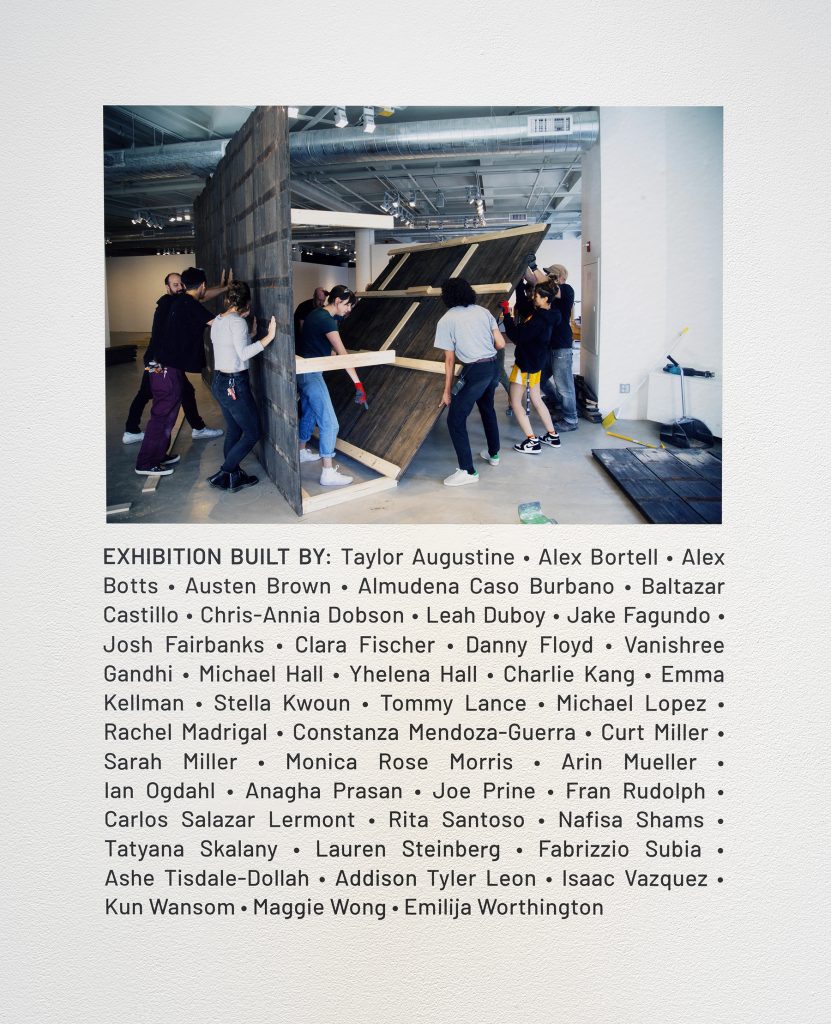

These anchor works are supplemented by a series of smaller scale projects in counterpoint. Many of these projects came out of the symposium work. Through ongoing conversations with participating artists, we encouraged risk-taking, experimentation, and new ways of working. As an exhibition in a school of art and design, we are bound by a different set of constraints and possibilities than those of other institutions. Modeling the principles we value as artists within the exhibition becomes essential. These include research, creative risk, and an embrace of the unknown.

Contributions by artist teams Josh Rios, Anthony Romero, and Deanna Ledezma; Julia Pello and David Hall; John Preus, high school apprentice/collaborators, and the Sweetwater Foundation; Caroline Woolard and Jessica Cook-Qurayshi; and individual artists Nneka Kai, Carole Frances Lung, Stephanie Rothenberg, and Gregory Sholette provide a complex web of associations and interweaving concerns.

The last phase of our project is still to come: a publication that embraces a true interdisciplinary spirit with documentation of the symposium, exhibition, creative experiments, and speculative contributions for the printed page.

It has been of critical importance to place into conversation works by young artists and proven masters, to have real intergenerational representation, and to contrast diverse perspectives and experiences, both locally and internationally. Similarly, diverse ways of working are represented through individualized practices as well as collaborative teams and new partnerships. Much as the nature of labor itself, there is both material and immaterial representation, intellectually driven artwork, and artwork that appeals to the senses.

We also have been mindful that our project include current students, recent graduates, established alumni artists, and faculty from SAIC—our intellectual base. Our intent is both inclusive and generative in spirit. We hope that these works will promote further exploration and involvement in the critical subject of our study, the contemporary condition of labor and work.

Once again, our task is to get the conversation going and to provoke creative response.